Nearly 200 years ago, James McGill, a fur trader and one of the most prominent slave owners in Quebec’s history, founded McGill University on land traditionally held by Indigenous peoples. On that land, enslaved Indigenous and Black labourers built many of the edifices which still stand on campus, including the Arts building. To this day, the university has not ceded the land that it stands on and during the 2015-2016 academic year, Indigenous students received just 46 of the 9,022 degrees granted by McGill. Last year, a task force created by McGill’s Provost Christopher Manfredi proposed 52 calls to action in order to address this history and the ways in which it continues to harm students on campus.

Part I: History

In 1859, McGill president and leading Canadian geologist Sir John William Dawson was called to a construction site at the corner of Metcalfe Street and De Maisonneuve Boulevard West, a block away from where McGill’s Bronfman Building stands today. Construction workers uncovered long-buried artifacts indicating the former presence of an Iroquois village: Fire pits, the infrastructure of longhouses, human skeletons, pottery, stone implements, and more. Some of these items are now visible at the McCord Museum.

Dawson spent a few months examining the evidence and eventually suggested that the site—which came to be known as the Dawson Site—represents the remains of the village of Hochelaga, populated by the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. In 1535, Jacques Cartier was the first European to discover Hochelaga when he reached the island that is today known as Montreal, after the French King Francis I tasked him with exploring what became New France. As he described it in his writings, Hochelaga was a large village of approximately 3,000 people living in 50 longhouses in a fortified enclosure surrounded by cornfields at the base of a mountain which he called Mount Royal. Scholars still dispute the exact location of Hochelaga, but because of Cartier’s description, most contemporary literature places it in the vicinity of McGill Downtown campus. Regardless, the village disappeared shortly after Cartier’s first visit; it was already gone by the time of his second, and no subsequent explorers were able to find it.

The connection between the Dawson Site and the St. Lawrence Iroquoian Hochelaga settlement has also faced criticism in recent years. In 1972, McGill anthropologist Bruce Trigger wrote Cartier’s Hochelaga and the Dawson Site with James Pendergast of the National Museum of Canada, and changed what had been until then the widely-accepted scholarship on the Dawson Site. Their book supports the view that the remnants found during the 1859 renovations belonged to a smaller village which existed on the outskirts of Hochelaga. A number of questions remain unanswered, however: Where on the island of Montreal was Hochelaga located, if not at the Dawson Site? What was the nature of the society that did leave behind the artifacts at the Dawson Site? What happened to these villages, and did their demise have anything to do with Cartier’s visit?

Whatever the answers may be, some facts remain certain. At least one group of Indigenous people resided on this land before James McGill or his university occupied it. Although they disappeared, the land has long been used as a place of meeting and exchange by the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe nations, as well as other Indigenous groups, none of whom were ever compensated for their displacement. In fact, McGill amassed some of the wealth he later used to found the university by selling and owning slaves, which was legal at that time in Canada. McGill owned or sold at least eight Black and Indigenous slaves, and as a member of the House of Assembly of Lower Canada, he voted against the abolition of slavery in 1793.

Progress away from this history and toward better treatment for Indigenous and Black scholars and Montreal residents by McGill University has been steady but tremendously slow. A little less than 10 years ago, Indigenous students accounted still only 0.8 per cent of the student body.

Part II: The “Task Force on Indigenous Studies and Indigenous Education” at McGill

In 2016, partly inspired by retired Academic Associate at the School of Social Work and member of the Mohawk community Michael Loft, Provost and Vice-Principal (Academic) Christopher Manfredi established a “Task Force on Indigenous Studies and Indigenous Education.” The Task Force’s foundation was also prompted by McGill’s upcoming bicentennial—the school will celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2021—and by Canada’s nationwide Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which released its final report in 2015.

According to Manfredi, the Task Force had a ways to go in consolidating McGill’s preexisting resources for Indigenous students such as the First Peoples’ House and efforts toward Indigenous student recruitment.

“The first step we took was actually to do a survey of what McGill is already doing in this area and as it turned out, we were already doing quite a bit,” Manfredi said. “But we weren’t very good at integrating what we were doing, we weren’t very good at publicizing it, and it was kind of all over the place. We hadn’t put a real focus around it.”

The Task Force’s final report, released in June 2017, ultimately specified 52 Calls to Action, which fell under five categories: Student Recruitment and Retention, Physical Representation and Symbolic Recognition, Academic Programs and Curriculum, Research and the Academic Component, and Building Capacity and Human Resources.

Kakwiranó:ron Cook, whose new administrative position as the Provost’s Special Advisor on Indigenous Issues arose from the Task Force, said that the new pace of progress has made him and many of his Indigenous colleagues optimistic.

“I’ve been here for a while, about eight years, and I can say that right now it feels like we’re in a fast-moving river, as opposed to being in a log jam,” Cook said. “It’s a process to roll it out, this takes a little bit of time, [...] but it’s good to be in that process right now.”

Cook directly attributes the speed of the movement’s progress to the administration’s involvement, but worries that future gains will continue to be contingent on its help.

“For me, the sense of urgency came from the fact that we needed the highest level of involvement,” Cook said. “We needed some coordination and some support directly from the leadership [....] Now that we’re there [...] we still need a lot of collaboration to continue aligning all of these things at McGill.”

Cook and Manfredi both agreed that one of their main projects as of now is to increase the financial aid packages available to Indigenous students. While their goal is to see 1,000 incoming Indigenous students by 2022, currently about half of the Indigenous students offered admission to McGill decline and go elsewhere, often due to the lack of financial aid available. In Fall 2017, only about 86 incoming students were Indigenous.

According to Associate Director of the First Peoples’ House Allan Vicaire, one of the biggest challenges Indigenous students face at McGill is a lack of visibility and companionship, often exacerbated by financial difficulties.

“I think the challenge for many of our [Indigenous] students is kind of that sense of belonging,” Vicaire said. “This isn’t just a McGill thing [...] I think when we look at all institutions across Canada, institutions were built for a specific type of student. And at that time, it was generally a white, male student.”

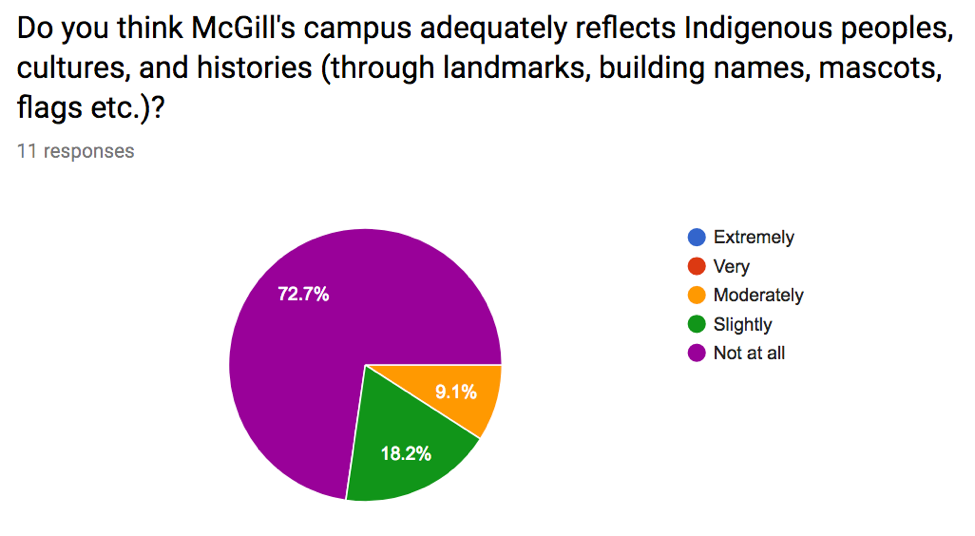

At McGill, the First Peoples’ House can provide an inclusive space: In an anonymous survey of Indigenous McGill students conducted by The McGill Tribune, 82 per cent of the 11 self-identifying Indigenous respondents cited the organization as a major source of support at school.

According to Vicaire and the students surveyed, however, the broader McGill community could do a better job of fostering a sense of inclusion. One student respondent wrote in the Tribune’s survey feedback field that increased awareness among non-Indigenous students could lead to meaningful improvements.

“Lack of education of my peers is one of the many challenges,” the student wrote. “Myself and many of my Indigenous peers have experienced direct discrimination, that in some cases likely could have been avoided with a simple non-colonial history lesson.”

A majority of the students surveyed also cited a lack of visual representation on campus as a barrier to inclusion. In January 2018, the Provost struck a working group on the “Principles of Commemoration and Renaming,” mandating it to follow up on the Task Force goals for “Physical Representation and Symbolic Recognition” and specifically its 21st call to action: “Varsity Teams and the McGill name.” The report suggested that McGill reconsider the name of its mens’ sports teams, which are currently called the “Redmen,” as well as building names and the name of McGill University itself.

Anja Geitmann, dean of the Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and associate vice-principal of Macdonald campus, is co-chair of the working group along with Robert Leckey, dean of the Faculty of Law. She explained that its goal is not to do the renaming itself, but to create a set of criteria to guide such decisions in the future, as schools like Yale University have recently outlined.

“I’ve always said to students that, whatever you want McGill to look like, it may not happen while you’re here,” Vicaire said. “But you also have to know that you’re part of the process. You’re going to push and make leeway, and it may not be the biggest jump, but the next cohort of students will then take what you were able to do and then push it a little bit further.”

“With the wisdom of hindsight it is easy to judge certain decisions that were taken in the past, and some we should probably have to reconsider,” Geitmann said. “Do we really want to continue commemorating certain people, or groups or entities, or should we not rewrite history?”

Cook said that other projects to include visibility include renovating Leacock Terrace with the input of Indigenous artists and architects, improving the Hochelaga Rock monument, which was moved to a more prominent location on campus at the start of the Task Force’s operations to create a dedicated ceremonial space, and raising the flags of Indigenous nations over the Arts building on significant days.

Vicaire acknowledged that change might be slow at an institution like McGill, but encouraged students to push forward anyway.

“I’ve always said to students that, whatever you want McGill to look like, it may not happen while you’re here,” Vicaire said. “But you also have to know that you’re part of the process. You’re going to push and make leeway, and it may not be the biggest jump, but the next cohort of students will then take what you were able to do and then push it a little bit further.”

Part III: Initiatives at universities across Canada

Other Canadian universities with more evolved programs may provide McGill with a sense of direction as it moves forward. Manfredi along with one of the students surveyed by the Tribune cited the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) as one such example. Manfredi suggested that the large proportion of Indigenous people at U of S and in the surrounding community accounts for their progress in tackling issues of inclusivity on campus.

Robert Innes, head of the Department of Indigenous Studies at U of S agreed, adding that about 10 to 12 per cent of the population of Saskatoon is Indigenous. Innes said that the U of S has about 2,200 undergraduate Indigenous students and 200 to 300 Indigenous graduate students, and that the Indigenous Studies department offers an undergraduate major and minor, as well as graduate, MA, and PhD programs. According to Innes, the hiring of more Indigenous faculty is an important factor which can expedite the improvement of conditions for students.

“Indigenous people in this city and province are highly visible,” Innes said. “[...In] Montreal that’s not the same, and even less so at McGill. I would say that the lack of a presence is a huge hurdle for students, because the faculty and staff at McGill will not have a real good understanding of the challenges faced by Indigenous students that are unique to Indigenous students. Really they won’t have the same level of understanding of the historical context in which Indigenous people are entering into McGill.”

Innes explained that a school like McGill might have trouble recruiting and retaining Indigenous staff under current conditions. Small hiring packages and relatively low wages McGill offers seem to indicate that the school is unaware of the highly competitive market for Indigenous professors right now, Innes commented. Furthermore, once on campus, Indigenous professors are often called upon to answer to or assist efforts in Indigenizing the school, and thus need extra support—or simply more Indigenous peers to reduce the workload—so that they don’t get sidetracked from their research, publication, and tenure requirements.

“Here at the University of Saskatchewan we have 50 to 55 Indigenous faculty, 10 in the department of Indigenous Studies itself,” Innes said. “[The McGill task force’s goal of hiring] 20 faculty would be great. But the thing about hiring 20 Indigenous faculty is [...that] there are going to be 20 Indigenous faculty scattered throughout the whole university, isolated from each other [....] In some departments, they’d be looked at as, ‘the only reason you’re here is because you’re Indigenous.’”

According to Eve Tuck, Indigenous associate professor of Critical Race and Indigenous Studies at the University of Toronto, one way of avoiding such an outcome is through a process called ‘cluster hires,’ where groups of Indigenous staff are hired in the same years, and influence or make decisions about hiring for subsequent cohorts.

“University administrators say ‘Indigenization,’ and what they say is simply bringing more Indigenous people into the same structures, into the same buildings, without much thought about what universities can learn from Indigenous communities, or what universities need to do to make good relationships with Indigenous communities,” Tuck said in an interview with CBC radio.

Innes also suggested that individual departments or faculties within universities could undertake their own hiring initiatives. At McGill, new Indigenous staff have been hired by the department of Anthropology and the faculties of Law and Agricultural and Environmental sciences in recent months. Mohawk is being offered as a language course for the first time this year, and Manfredi said that he was hopeful the Indigenous Studies minor would be expanded to a major program within the next 10 years. Yet, according to Innes, McGill should closely watch whether Indigenous staff stay or go.

“The resources are there,” Innes said. “This will be the test, to what degree is McGill sincere about what they want to do? So far, they have produced a report [....] If they can’t retain [Indigenous staff], even if they can recruit them, it’s going to be hard to recruit Indigenous students, and it’s going to be hard to get confidence from the Indigenous community.”

Another venue for meaningful change which Innes discussed is requiring students to take an Indigenous content course. He said that for the past 15 years, the colleges of Kinesiology, Social Work, Education, and Nursing at the University of Saskatchewan have required students to take either a half or full credit class in the department of Indigenous Studies, and that beginning in 2020, their college of Arts and Sciences will begin requiring its freshman class of nearly 2,000 students to do the same.

Manfredi said that there has been some discussion around the idea of such mandatory classes at McGill, but that for the time being the question would be left to individual faculties, depending on whether the content could be integrated into their curriculum.

“The resources are there,” Innes said. “This will be the test, to what degree is McGill sincere about what they want to do? So far, they have produced a report [....] If they can’t retain [Indigenous staff], even if they can recruit them, it’s going to be hard to recruit Indigenous students, and it’s going to be hard to get confidence from the Indigenous community.”

“I think there’s differences of opinion around mandatory courses,” Manfredi said. “Sometimes if you make things mandatory, people may not take them as seriously as they should.”

Cook and Innes both acknowledged this challenge. However, Cook described an enormous knowledge gap in non-Indigenous members of the McGill community, and argued that designating spaces and classes for them to improve their awareness could prove to take a large burden off of their Indigenous counterparts. Cook, who is an enrolled member of both the Mohawk Nation at Akwesasne and the Oglala Lakota Sioux Nation at Pine Ridge, described feeling like an ambassador who regularly has to explain his own history or that of other Indigenous groups, but is still met with disrespectful behaviour, such as people who avoid learning or saying his full name.

“I think people need to create a dedicated space to seriously consider that,” Cook said. “It’s quite an undertaking. Me, as an Indigenous person, yes, I can’t tell you what it’s like. We are affected by colonization every day [....] Most people don’t know about the land here, and the people here, and the ceremonies here, that we’ve been here for thousands of years, and people just aren’t exposed to that in school [....] So there’s a lot to be said, if you ask any Indigenous person, well, yeah, we are missing. We’re invisible in the curriculum. Nobody knows about us. So it’s a lonely experience. It’s lonely.”

About the survey:

The student survey referenced in this article does not meet scientific standards.

The author of this article distributed the survey to the McGill student body using an anonymous Google form. The survey included a combination of multiple-choice, Likert scale, and open-ended questions about Indigenous student experiences at McGill University.

During the data-collection period, the author posted the survey link to various McGill community groups on Facebook and Reddit over the course of three days from March 27 to March 29. In total, 11 students responded to the survey.