When I first applied to McGill in the middle of the pandemic, I had never stepped foot in Montreal, much less onto McGill’s campus. In an attempt to recreate a traditional university visit, I watched McGill’s promotional videos, trying to weave video fragments of the campus together to imagine the place I would call home for the next four years. Images of the Arts Building, with the McGill flag waving red and white from the top of the dome, and the Macdonald-Stewart Library Building with its half-moon windows were ingrained in my mind. What I didn’t anticipate, and what was never shown in these videos, was the constant noise of construction across campus. Buildings that McGill presented to me as the cornerstones of campus were, in fact, covered in scaffolding when I arrived.

McGill’s campuses are always going to be a work in progress. The inevitable trade-off is that historic buildings, while beautiful, require frequent maintenance to ensure that they meet modern building codes. McGill has 200 active construction projects at any given time, according to McGill Media Relations Officer Frédérique Mazerolle, due to the campuses’ sheer number of aging buildings and new construction undertakings. These projects range from the installation of electrical sockets to the New Vic project which is estimated to cost at least $700 million. According to Mazerolle, McGill allocates about $150 million to construction projects annually.

McGill is currently playing catch-up to address all of its buildings’ maintenance issues, such as the ongoing construction in the Macdonald campus’ Raymond Building and Centennial Centre. As projects get underway, new ones are slotted for future maintenance and different issues sprout up that require even more work. The inventory of construction projects has become larger than what funding can provide. This results in deferred maintenance, which refers to the stalling of projects that are slated to be completed. And now, as the institution stares down the reality of climate change, broader changes to the campus have to be made to adapt; changes that cannot be prioritized until deferred maintenance is resolved. How did McGill get to this moment, and what does it mean for its built environment?

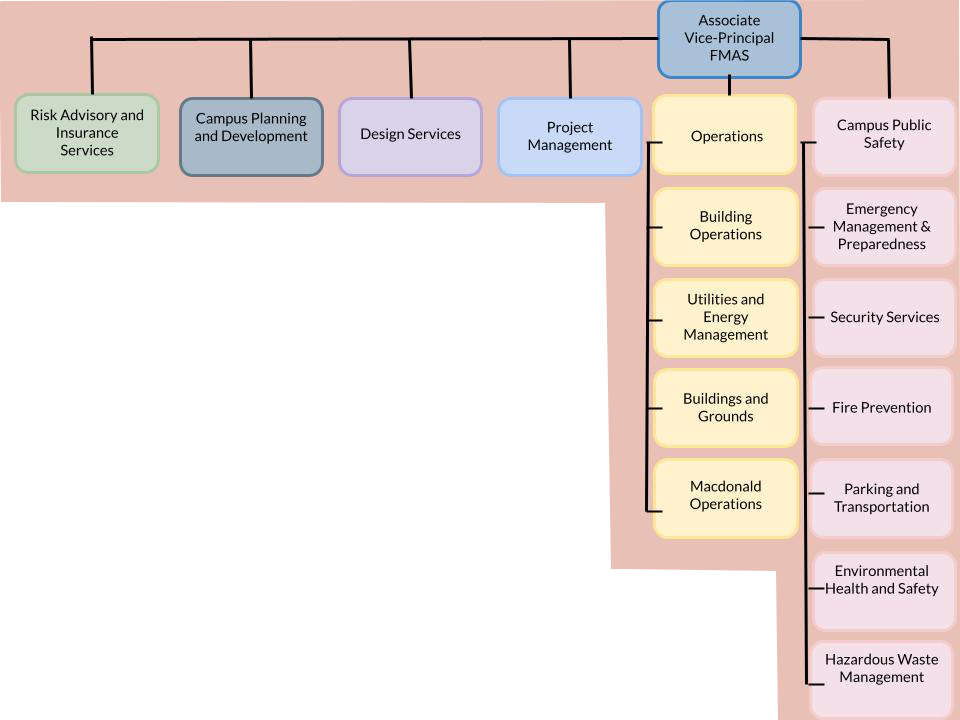

Facilities Management and Ancillary Services (FMAS) is the department that oversees and plans construction at McGill. FMAS comprises six units: Operations, Campus Planning and Development, Design Services, Project Management, Campus Public Safety, and Risk Advisory and Insurance Services. It is clear that McGill’s priorities lie in management and maintenance; even in name, the department is focused on management rather than planning, with the latter being a subset of the department rather than its primary focus. Currently, the department oversees at least half a billion dollars worth of construction projects across the Downtown and Macdonald Campuses.

Climate change is no longer a vague phenomenon looming on the horizon; we are already witnessing the faults of McGill’s infrastructure and how climate change alters the environment we live in. As the beginning of the Fall semester feels hotter and hotter each year, and walking into the non-air-conditioned Arts Building for class offers no relief, the effects of climate change are palpable. Predictions for the Montreal area suggest that the summer heat trend will only worsen, and the region will experience much more precipitation. Extreme weather events such as flash floods and ice storms are also expected to be increasingly common.

Michael Jemtrud, associate professor in the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture, told The Tribune that the most sustainable buildings are “the ones that are already built.” According to him, the problem is not in the resilience of McGill’s current buildings but in the planning being done at the institutional level. He believes McGill and FMAS need to be better funded for front-end risk management and as a complement, to focus more on long-term planning rather than maintenance of buildings in order to transition the university’s infrastructure to one that is climate-resilient.

“I personally think [McGill is] way underestimating climate change models,” Jemtrud said. “I think the five-year model [for climate change] was actually the twenty-year model. We have to be prepared for that and we have to plan our infrastructure accordingly.”

While FMAS’ Campus Planning and Development unit released a Master Plan in 2019 that outlines the long-term goals for both the Downtown and Macdonald campuses, little progress has been made toward these goals so far. Factors such as the need for maintenance, the pandemic, and now post-COVID inflation, have stood in the way.

Jemtrud, who is working on the BARN project—a new interdisciplinary research facility with a focus on decarbonization—on the Macdonald campus, told The Tribune that his team has faced bureaucratic roadblocks involving zoning issues that have delayed the project. With inflation, the grant he received pre-COVID is insufficient for the project, so the team has had to find alternative funding options. Jemtrud believes this speaks to the inefficiencies of FMAS as he thinks these issues could have been avoided by putting more money into research early on in the process.

“We need to have a more serious planning department, maybe campus architects, someone who’s looking at this in a different way, who’s more familiar with new construction,” Jemtrud said. “We need to fund that department as well as FMAS because this kind of cost-recovery model that the university has adopted as if we were some corporation—which we’re not, we’re publicly funded—doesn't work if you want to do strategic planning. In my opinion, it doesn't work if you want to do proper risk management.”

In McGill’s construction projects, they work to meet certain sustainability objectives, one being Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design ( LEED) certification. Jemtrud said that these objectives do not necessarily constitute sustainable infrastructure and in some cases are performative rather than substantially progressive toward sustainability. Jemtrud proposes thinking about innovative solutions and involving the experts who work and study at the institution.

“It sucks to have to plan for the worst-case scenario, but I think you’re foolish if you don’t at this point. On a day-to-day basis too, I think, there are ways that we can start to look at maybe some not-so-obvious solutions to things, use our expertise a little bit more, be leaders in using low carbon [design]— Seriously, though, not just the greenwashing is all too common in our industry.”

McGill cannot hope to plan for the future if it is already struggling to keep up with the necessary maintenance needed for its aging infrastructure. Nowhere is this more evident than on the Macdonald campus. According to FMAS’ maps of current construction projects, over half of the construction budget at the Macdonald campus is allocated to deferred maintenance.

Mazerolle explained that in 2020, McGill “launched a $100-million building renovation program at Macdonald Campus,” and that the renovations “involve critical—and long-deferred—upgrades needed to bring the campus facilities up to modern building codes and standards.”

That means that the maintenance is long overdue but was delayed because of constraints, whether financial, labour-related shortages, or the prioritization of maintenance elsewhere. Anja Geitmann, Dean of the Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and Associate Vice-Principal (Macdonald Campus), spoke to the obstacles faced when it comes to keeping up with maintenance at Mac.

“The amount of aging buildings that McGill has with respect to other Quebec universities is probably higher than most others,” Geitmann said. “The total number of buildings, the situation on the labour market, the situation on the construction market, is really an overall perfect storm that lands us here in 2023 with a whole lot of challenges.”

Coupled with these obstacles is McGill’s consistent deprioritization of the Macdonald campus versus the Downtown campus.

“Each individual prioritization that a provost might have done in the last few decades might have made sense,” Geitmann said. “If you see there’s a building downtown that services 10,000 students versus a certain building at Mac that services 2,000 students [...] in that moment, that decision makes sense to go for the building that services 10,000 students. However, if you do that five times in a row, you never get to that building that only serves 2,000 students. So it’s a series of decisions where the global consequences were maybe underestimated in terms of what that means for Macdonald.”

When I walked around the campus with Meryem Talbo, President of the Macdonald Campus Graduate Student Society (MCGSS), the effects of the administration’s years-long neglect of the campus were clear. The Raymond Building, which houses the Department of Plant Science, has been closed for deferred maintenance since the fall of 2021. According to Geitmann, the building housed fifteen research labs and four classrooms that cannot be used until construction ends, tentatively in the fall of 2024. Talbo told me that while the loss of these spaces perhaps would not be significant on the Downtown campus, they certainly are on the Macdonald campus.

“It’s ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ ” Talbo told me. “It’s a smaller campus, smaller student population, it's [far away] [....] I completely understand the logic behind [prioritizing the Downtown campus], but I do think it's a little bit flawed because you're still impacting people's lives. And students’ lives and their work and their research and their development in your institution. And here, because it's a smaller campus, if you remove just a little bit, it's felt. Like, if you close just one side, you lose half of your lab space.”

Neglecting maintenance on the Mac campus for so long has led to a situation where many maintenance projects—albeit, much-needed—are occurring at the same time, disrupting research and classes significantly. Being a smaller campus, flex spaces are harder to come by. In the severe case when McGill abruptly closed the Raymond building last winter due to asbestos, it put additional pressure on the already strained campus to find space for people who had lost their lab spaces. Talbo told me that, specifically with the Raymond building closure, multiple graduate students’ research was disrupted which, in some cases, delayed their graduation dates.

“A lot of my friends for example [...] their labs are wet labs, and everything was shut down. You have some experiment that you need to prepare for for weeks, suddenly shut down and you can't access it. So that definitely impacted a lot of people, a lot of students as well. Either the projects needed to be further pushed, sometimes they needed to be canceled, or the students themselves needed to push their graduation dates [....] It definitely impacted not just the morale, but also the students’ [lives].”

There are many factors that play into the ineffectiveness of McGill’s infrastructure management, but underlying them all is the need to focus energy on long-term planning as opposed to patching up holes when they sprout up. While we spend a few years at this institution, expecting instantaneous change, the built environment that we engage with will continue to impact generations to come.

“It's a complicated issue and it's even more complicated now that [we’re getting] through this horrible phase of the deferred maintenance or a big chunk of it, but now we've got the Royal Vic on our plate, and we've got climate change on our plate,” Jemtrud said. “So I think it’s even more important now than ever to kind of rethink: Do we have the right structures in place to deal with all of that?”