In a corner of the exhibition’s second room, Émilie Charmy’s Still Life with Pomegranates sits beside Jacqueline Marval’s self-portrait Minerva. The scenes in oil are classical: Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, condemned to the underworld for six months for eating six pomegranate seeds, resurfacing in the spring only to descend six months later back into hell, becomes stained in rich red on Charmy’s canvas, where six open pomegranates spill onto a white platter. Marval’s Minerva stands in the woods holding a spear; the artist’s name emblazoned in large red letters across the bottom of her breastplate. Marval trained as a seamstress and signed her name on her image’s clothing as if embroidered onto the armour’s scales. The scenes are reimaginings, but ones that are true to the myths they spring from—women painting themselves into the past, not to insert themselves into history, but to tell the stories where they’ve existed all along.

We don’t know if Minerva hung in Berthe Weill’s gallery—documentation surrounding the painting is limited and scholarly work to unearth Weill’s life is ongoing. She was, routinely and repeatedly, by both historians and her contemporaries, written out of the story of the Parisian Avant-Garde and modern art as a whole.

Weill, a lifelong Parisian, grew up in an Alsatian Jewish family. Though she was raised without money and often struggled to stay afloat throughout her career, she displayed a categorical indifference to profit. She believed in her artists and the art they produced, did not charge them to exhibit their work (as her contemporaries did), and refused to exhibit art for its monetary value.

As Weill writes in her memoir, Pow! Right in the Eye!, “I would rather eat bricks.”

Berthe Weill, Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde is a joint force between Montreal, New York, and Paris, curated by Anne Grace, Curator of Modern Art at the MMFA; Marianne Le Morvan, founder of the Berthe Weill Archives; Lynn Gumpert, former Director of the Grey Art Museum at New York University; and Sophie Eloy, Attaché to the Collection at the Musée de l’Orangerie.

“We were able to draw attention to artists that certain museums have in their collection that they were not even very conscious of,” Anne Grace said in an interview with The Tribune.

The exhibition—centered around an art dealer as opposed to an artist—produces a polyvocal picture of Belle-Époque Paris: The story of artists who came and went, works Weill sold, and those she championed against the grain.

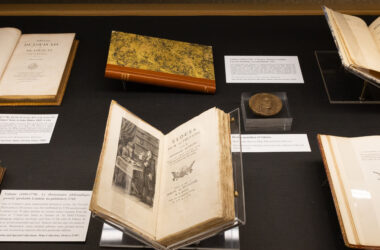

The resulting recreation compresses time and extrapolates space. Forty years spanning the first half of the 20th century in a small Montmartre space are transformed into a major exhibition spread across several rooms in Montreal. Modigliani, Picasso, Cézanne, and Chagall are displayed amongst invitations to costume balls at the gallery, bulletins, and courtroom sketches. Weill’s spectacles lie lens-less and unlabelled in a glass case beside an ink portrait of the dealer by Édouard Goerg.

Weill did not train in an art gallery, but in an antique shop. It belonged to her cousin, Salvatore Mayer, and upon his death, Weill opened her own antique shop alongside her brother. The shop transformed into a gallery of her own, carefully named so as not to reveal the dealer’s gender. Galerie B. Weill opened in 1901.

She lined her gallery with paintings, but also prints, pendants, pottery, sculptures, and jewelry.

“She, in general, had this openness and complete disregard for hierarchies [….] She probably finished school around the age of 10, when public education for girls stopped. So she wouldn’t have necessarily had this ingrained notion of hierarchies in medium or subject matter,” Grace said.

When Weill met Amedeo Modigliani, he was drunk in her gallery; two years later, in 1917, she became the first—and only—dealer to organize a solo exhibition of Modigliani’s works during his lifetime. The exhibition was later shut down by order of the police commissioner. The nudes had pubic hair. This overwhelmed many viewers. The commissioner took Weill into the local precinct for questioning: “Those disgust-” he exclaimed to Weill. “They…they… h-h-h-have hair!” No works were sold, save for those that Weill purchased for herself.

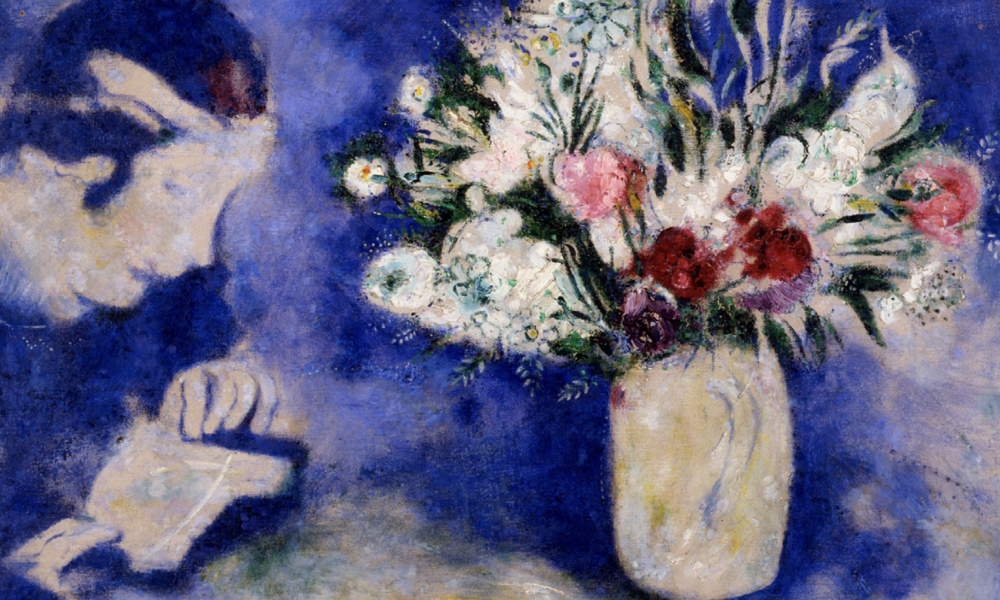

Weill wanted to exhibit young artists, the unknown names—a group she affectionately referred to as “les Jeunes”—and championed émigré artists in Paris. The vibrant world of 20th century art is spread out across the exhibition. In the first room, there’s The Wretched, a mass of intertwined bodies in bronze by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller—an African-American sculptor who would train with Rodin in Paris before returning to the U.S. to sculpt the Harlem Renaissance. There’s The Bird Cage by Marc Chagall, a Jewish Russian-French modernist, featuring an anthropomorphic rooster-man in purple pants playing a fiddle. There’s Marie Laurencin’s Woman Holding Flowers, a gossamer scene in oil (the label recounts the story of Laurencin, a queer cubist painter, bursting into Weill’s gallery and declaring, “I want to meet a lesbian!”).

Suzanne Valadon’s Nude with a Striped Blanket, or Gilberte in the Nude Seated on a Bed shows her niece, nude, sitting with her legs swung onto the floor at the foot of her bed. She’s slightly slouched. Her form is not contorted for show: Not spread, not bent, not splayed. I recognize her body’s configuration—how she stretches her legs, how she leans, how she reads, the creases and folds on her stomach—it’s how I sit.

Valadon painted women who exist as they are, without a voyeur. It’s a nude form that doesn’t exist to produce desire.

The movements that Weill championed—Fauvism, Cubism—are those that took reality and refused to canalize it into something empiric or straightforward. They mirror the approach that Weill herself took in her indifference to profit: She desired something beautiful and intangible that focused on the heart of the art itself, as opposed to trying to turn it into something material and marketable. In her lack of education, lack of money, lack of opportunities, Weill reached inward to find what art moved her, and in looking outwards, advocated for art that subverted the language of production that she herself had never desired to speak.

A vision of the body that doesn’t exist to yield desire. Art that doesn’t exist to yield money.

In 1940, the Nazis invaded Paris. Le Cahier jaune—an antisemitic French periodical—published a virulent attack on Weill, writing that she was greedy, caring only for money and not for art. Weill went into hiding, transferring her gallery to a non-Jewish friend in an attempt to save it. A year later, Galerie B. Weill closed forever.

Weill survived the war. Details of her life under occupation are obscure, made more difficult to pin down because Weill had to make herself hard to find in order to have a chance at survival. Two of her artists, Otto Freundlich and Sophie Blum-Lazarus, died in concentration camps.

Photographs of Weill from any period are hard to come by. Portraits of her are limited, and those that exist and survive, namely Émilie Charmy’s Portrait of Berthe Weill, show her standing upright, unsmiling, her five-foot frame swallowed by a large black coat buttoned up to the neck, her left sleeve rolled up to reveal a wristwatch.

“She really focused her attention on the artists themselves, and not herself. So the self effacing aspect, I think, is revealed in both her physical appearance, the way she dressed and the lack of portraits, whether they be painted or photographic portraits,” said Grace.

Contrary to the lack of images of Weill, she is thought to be the first art dealer to write and publish her memoirs during her lifetime (she beat out the publication of her rival dealer Ambroise Vollard’s autobiography by a year).

Berthe Weill died in 1951. She was blind. Weill—who had never married, and used her dowry to fund the gallery in its early days—was left destitute in the wake of the war. In her last years, as her health declined, the artists Weill had championed early in their careers, when no one else would, organized an art auction to raise money for her care. Chagall, Picasso, Metzinger, and other prominent artists and gallerists raised 1.5 million francs for the woman they called Mère Weill—a homophone with “merveille,” “wonder” in French—and supported her until the end of her life, as she had once supported them.

Berthe Weill: Art Dealer of the Parisian Avant-Garde will run until Sept. 7, 2025. Tickets are available online or in-person at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Weill’s memoir Pow! Right in the Eye! Thirty Years behind the Scenes of Modern French Painting is available in print and as an ebook through the McGill Library.