While all of the clinical rotations in which medical students participate are challenging, one of the most intimidating rotations is general surgery. This is not surprising given what is at stake in an operating room (OR).

“First of all, you have to understand sterility and how not to contaminate the table,” Dr. Mirko Gilardino, plastic surgeon and professor of surgery at the McGill University Health Centre, said in an interview with The Tribune. “And then there’s this old adage that surgeons are grumpy […] [although] that’s not necessarily true, of course [….] But still, it’s scary and overwhelming, nevermind the fact that there’s a body that’s being operated on.”

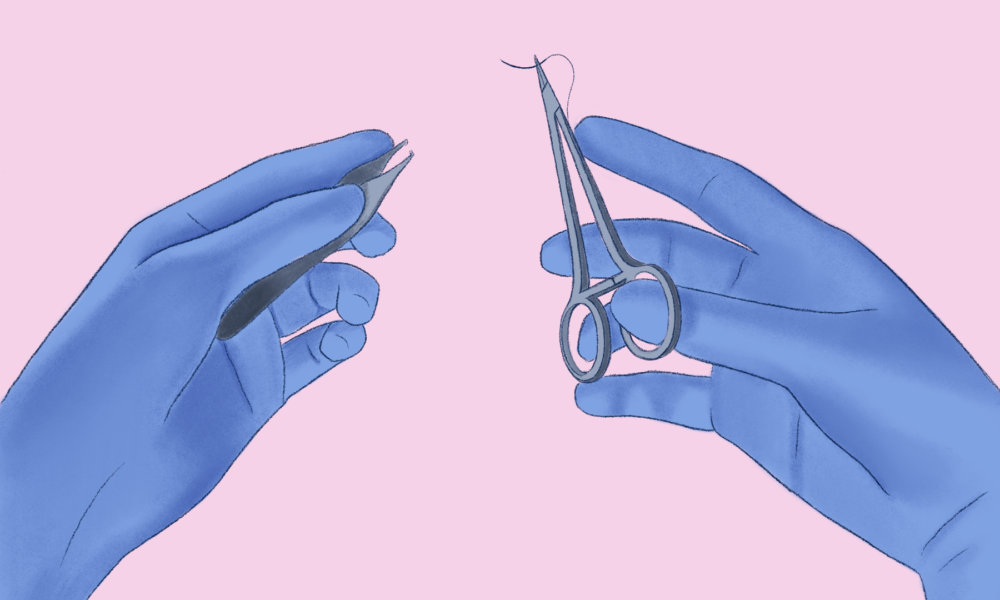

Despite how stressful it may be, spending time in the OR as a medical student is an incredible opportunity to practice and apply one’s basic surgical skills, such as the skill of suturing—stitching a patient’s wound or incision closed. Therefore, learning to suture with confidence before getting to the OR is a huge asset.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Surgical Education, Gilardino, along with Dr. Hassan ElHawary—the paper’s primary author—and their collaborators examined how training medical students to suture with their non-dominant hand affected both their skill acquisition and their confidence.

They assessed the medical students’ aptness for suturing on practice material using both their dominant and non-dominant hands, before and after training. One group of students completed the suturing training with their dominant hand, while the other trained with their non-dominant hand. Afterwards, the researchers administered a questionnaire to assess any changes in the students’ confidence in their skills, how well they could use them in the OR, and how they perceived the ambidextrous training.

The authors found that both groups of students improved their one-handed suturing skills to the same degree. Furthermore, they discovered that those who had trained to suture with their non-dominant hand actually improved their dominant-handed suturing as well. Both groups of students generally reported increased levels of confidence in their surgical skills and in their ability to use them in the OR. Finally, many of the students expressed that ambidextrous training should become standard practice in surgical education.

Rather than being driven by an interest in ambidexterity alone—although this was a key focus—this study was born out of a more general desire to improve how surgical skills are taught, and to do so in a way that makes students more comfortable with the idea of surgery.

“Hassan was really interested in what he called ‘surgical workshops,’” Gilardino said. “So what he felt was that students didn’t enter or didn’t even seek out careers in surgery, unless somehow they were exposed and had a positive experience.”

After seeing how successfully the workshops were running, ElHawary realized the research opportunity sitting in front of him.

“Hassan thought about it, and he was like, ‘Wow, you know, people are liking surgery more. I wonder if we can even do it better by training them on their non-dominant hand,’” Gilardino recalled. “It was more like a curiosity. And since you already had the whole structure in place and his courses, it wasn’t that complicated for him to dive into this.”

There are many benefits to being a surgeon who is adept with their non-dominant hand. For example, some operations are better suited for right-handed maneuvers, and others are better suited for left-handed maneuvers. It is useful to be able to tackle a problem from both sides. Surgical ambidexterity has also been shown to improve both the efficiency and the outcome of an operation.

Overall, this study underscores the need for surgical education that not only encourages training with one’s non-dominant hand but that builds a sense of confidence in medical students at the same time.