The International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation (IBSF) has denied the allegations of Olympic ‘sabotage’ involving the Canadian national team and cleared the coaching staff of any wrongdoing. The controversy stems from American skeleton veteran Katie Uhlaender, a five-time Olympian whose hopes of competing at a sixth Winter Games Milano Cortina were swiped from her despite winning a key qualifying race.

The disagreement came down to how skeleton athletes earn Olympic qualification points. Points are not only based on finishing position, but are also tied to the size of the field. The more athletes in a race, the more points are available. In this situation, four of the six Canadian women who had originally been entered in a North American Cup race in Lake Placid from Jan. 7 to 11 were withdrawn before competition. That significantly reduced the field size, which lowered the total points that could be earned. Although Uhlaender won the race, the reduced points haul meant she could no longer qualify for the Olympics.

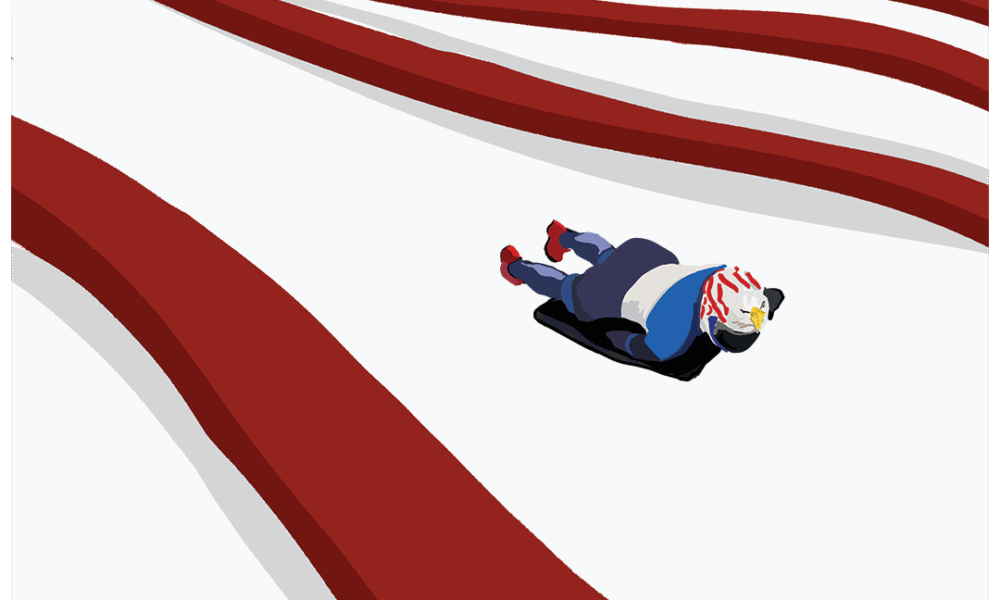

Uhlaender, one of the most experienced athletes in the sport, accused the Canadian head coach of intentionally withdrawing athletes to manipulate the points system. From her perspective, the decision was a strategic move to protect Canada’s Olympic spots by limiting the ability of rival athletes to earn points. This was perceived as a clear message that even winning was not enough when tactical decisions could override performance.

Bobsleigh Canada Skeleton (BCS) has strongly rejected those allegations. The organization insists the withdrawals had nothing to do with points or Olympic strategy, but instead had everything to do with athlete welfare. According to BCS, the athletes who were pulled were young and relatively inexperienced, and they had already endured a difficult week on a demanding track. After assessing their readiness, coaches concluded the athletes were not prepared to race for a third consecutive time, and withdrawing them was framed as a responsible decision rooted in safety and long-term development.

This clash of perspectives highlights why the situation has become so controversial. On one hand, Uhlaender’s frustration is entirely understandable. Winning a qualifying race is usually the only thing that matters, and for athletes who have worked for so long to achieve this dream, having it stripped away would be devastating. The idea that another team’s roster decisions can determine the value of a victory feels fundamentally wrong, especially for something as highly regarded as Olympic qualification.

On the other hand, Canada’s explanation cannot be dismissed outright. Coaches regularly make judgment calls about athlete readiness and risk, particularly in extreme sports like this, where mistakes can lead to serious injury. Athlete safety is not a convenient excuse; it is a legitimate reason and is necessary to protect the team and its athletes.

The deeper issue seems to lie not in proving malicious intent, but in the structure of the qualification system itself. The fact that this controversy is even possible exposes a colossal flaw in how points are awarded. A system where the withdrawal of athletes could alter another competitor’s participation is logistically unsound. Even if Canada acted in good faith, it is hard not to see how it could have been manipulated.

Ultimately, this controversy is not just about Canada versus the United States or athlete versus federation. It is about whether Olympic qualification systems truly reflect athletic performance. The investigation may have determined responsibility, but it is clear to see that when winning on the track is not enough, the system itself needs reform. Olympic dreams should fall to the fate of hard work and performance, not the unintended consequences of decisions made behind the scenes.