Despite being friends with several physics majors, when discussions of gravity and inertia inevitably shift into abstract theory, I can’t help but wonder, what is physics all about, anyway?

If you’re studying science or engineering here at McGill—or just interested in the mysterious inner workings of physics overall—there’s a pretty high chance you’ll find yourself at some point or another sitting in Leacock 132, as one in a sea of 650 students, taking an introductory physics class.

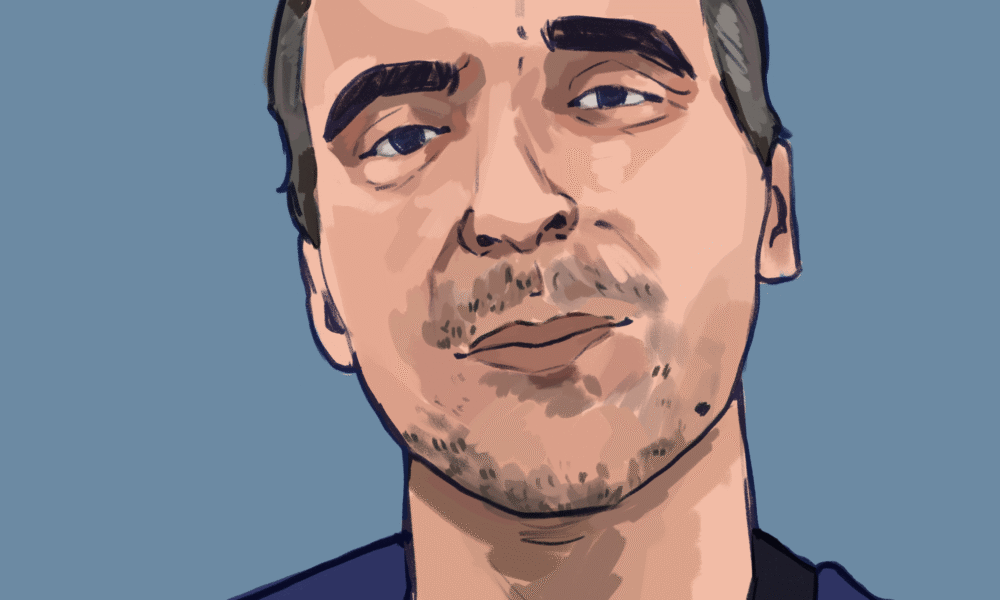

PHYS 102 is one such introductory course. In this introduction to electromagnetism, students learn the fundamentals of electric current, circuits, magnetism, and optics. These concepts are not only interesting but foundational to later studies in physics and engineering, and McGill students are in good hands: PHYS 102 is taught by Nikolas Provatas, a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair and member of the Department of Physics.

Like many scientists, Provatas traces his interest in science to early childhood. In an interview with The Tribune, he recalls being just seven years old when a picture book about Galileo Galilei and his theory of the pendulum captivated him.

“At that age, I had no clue about equations or anything, but I remember the text said that [Galilei] observed [his theory] by watching […] how long it takes the chandelier to swing,” Provatas explained. “So when I would go with my father to [his] restaurant in the morning, around 5:30 a.m. […] it would take a long time till things got busy. [So], I remember I took up a string, and I tied a little mass at the end of it. I can’t even remember what it was, [it] must have been a cup or something. And I would tie it somewhere, and I would just swing it in the kitchen and just watch it. And I remember my father looking at me, thinking, you know, like, ‘Do something productive with your life,’ [….] And I thought, ‘This is productive. The scientist did this. I’m trying to figure out how it works.’”

From here, Provatas’ curiosity continued to grow, eventually leading him through post-secondary education; he graduated from McGill with a PhD in theoretical physics in the late 1990s.

Given that he was interested in how the world works and why it works the way it does, Provatas found theoretical physics to be a natural fit. Unlike experimental physics, which focuses on data collection and analysis, theoretical physics relies on math and other models to explain phenomena.

After completing his PhD, Provatas went on to complete two postdoctoral positions—temporary research positions—where he explored different areas of physics. He emphasized the importance of these experiences, describing them as the academic equivalent of a doctor’s residency training.

“Labs hire you on a contract basis, and say, ‘Solve a problem or do something interesting, and then we’ll pay you to do that, and then we publish together.’ So I do the work, I publish, and then they provide me [with] some environment [or] ideas,” Provatas said.

His first postdoc was in Helsinki, Finland.

“I spent three years at the University of Helsinki, at their Institute for Theoretical Physics, doing work there on something called Percolation theory,” Provatas explained. “It’s a theory of how random things diffuse through materials so as to percolate through them, and this is very important when considering the structure of materials, ranging from paper to even metals.”

After his time in Finland, he completed a second three-year postdoctoral appointment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

It was after this second postdoc that Provatas began searching for stable work. Life as a postdoc is inherently uncertain; each job is contracted for a specified number of years, after which researchers are left to find new roles, potentially on opposite ends of the globe.

“I literally owned nothing because I knew that in any apartment I would go, whether here as a PhD, in Helsinki as a postdoc, [in the] United States as a postdoc, I knew I couldn’t really buy stuff because I’d be on the move in a couple of years,” Provatas explained. “So literally, I would just have my backpack and a suitcase to hold some clothes, and that was my whole ownership at that time.”

At UIUC, he worked under two professors: one in statistical thermodynamics and another in mechanical engineering. Mentorship from this engineer proved to be pivotal to Provatas’s future career, as he taught him how to communicate his research in ‘engineering terms’ rather than purely theoretical language

“He taught me how to talk the talk and walk the walk of engineers, and to focus on what’s important when you sales pitch your stuff to engineers versus just pure scientists,” Provatas said. “And he actually made me wear a suit to give conferences. And I started to go to engineering conferences and give seminars.”

It was through attending these engineering conferences that Provatas was able to land a job at Bush Paper Company, working as a Research and Development scientist. Eventually, through his work at Bush, Provatas was invited to apply for a professorship at McMaster University—not in the physics department, but rather in the materials science and engineering department.

“I thought, ‘Oh, boy, you know, this is nice.’ I’ve always wanted to be a prof, but I thought it’d be a physics prof.” Provatas said. “I didn’t know I’d go work as an engineering prof. So I practiced and practiced and got over the fear, and I went and gave an interview, and to my shock, they hired me.”

Provatas worked at McMaster for 11 years. It was only after an opportunity to teach physics at the university level—as opposed to materials science and engineering—that Provatas left McMaster. This opportunity was from none other than McGill University.

“I’ve been here since 2012, teaching physics, doing research on the same topic. I’m still a material scientist, but looking at it from a very physics[-oriented] point of view,” Provatas explained. “What ultimately made me make the transition from an engineering department to a physics department, is that you know, you can ask the questions that, on one hand, they could be useful, but on the other hand, it could be very impractical, but you know, it’s there. So, ‘Why does gravity work?’ So someone might say,’ Oh, come on, do something important [and] practical with your life,’ but [gravity is] there. I see it. It acts on me every day.”

As a professor, whether at McMaster or at McGill, Provatas has always taught freshman courses. Classes like PHYS 102 allow him to connect his research to his course content, finding ways to keep the material engaging and interesting for students.

“I always like to take what dry theory we’re learning, and say, you know, ‘this is important, because power generation works this way. Let me show you how making material works this way. An aircraft works this way.’ And I find that students like the fact that it is connected to the real world. It’s not just ‘Oh, I’m sitting here in a physics class learning all these equations.’”

Provatas’s current research focuses on understanding the microstructures of material—in other words, how they form and how they respond to material phase changes.

“If you now explore the depths of this material, at the level of atoms and thereabouts, you start to see that the material is just not some monolithic, boring object. It’s a myriad of interesting patterns [and] that the atoms [are] forming the tapestry of a solid form,” Provatas explained. “My research focuses on why these patterns form […] how they form, [and] what controls their formation. And it’s beautiful.”

This semester, Provatas is teaching PHYS 102 and PHYS 657—but anyone interested in learning more about physics or materials science is welcome to stop by his office hours: 3:30 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Mondays, in Rutherford 218.

While Provatas’s path to McGill wasn’t linear, his interests and curiosity led him to a career of research that his seven-year-old self may not have even been able to imagine. Ultimately, Provatas shows that the trick to life is the same as the answers to PHYS 102: Achieving through dedication and hard work, and seizing the opportunities in front of you.