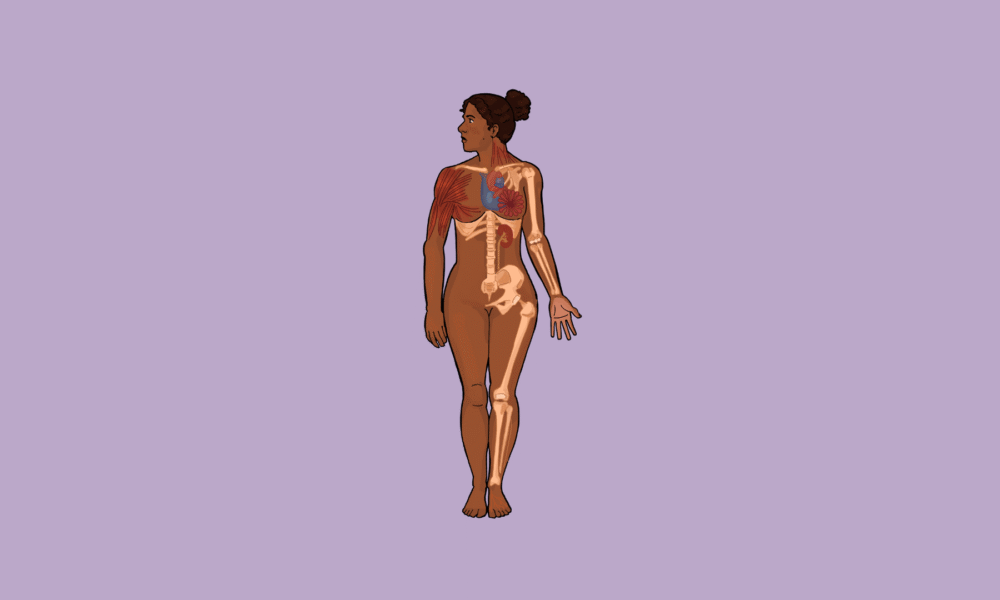

To be a woman is to live within systems designed without your body in mind. Whether or not this divide is felt or acknowledged is a far more personal question, but regardless, the reality remains: The marginalization of women is fundamentally ingrained in Western society. From endless bathroom queues to uncomfortable seatbelts calibrated for male bodies, the male lived experience is systemically privileged in all aspects of life—even the most mundane.

This foregrounding is not always benign. It is more than a general inconsideration of the female social experience—the lack of free and available menstruation products in public restrooms, and the absence of garbage cans in restroom stalls for sanitary products, for example—it is a pervasive diminution of women’s physical and mental agency.

This marginalization is especially prominent in the medical sphere, a sector historically designed by men, for men. Women’s pain is frequently ignored or dismissed as ‘exaggerated.’ Their concerns are attributed to menstruation or anxiety, and diagnostic criteria and treatments centre on male symptomologies, rendering women’s experiences as secondary within their own care.

Systemically, this places women in the centre of a social schism: Women face pressure to remain healthy, yet are continually prevented from accessing adequate health resources when they have medical concerns. While progress has been made, the medical system is still failing women—especially Indigenous women and women of colour.

To gain true social equality, medical biases must be addressed.

//Women and the medical gaze//

Women have been notoriously excluded from medicine throughout history. McGill’s first graduating medical class to include women —Winifred Blampin, Jessie Boyd Scriver, Mary Childs, Lilian Irwin, and Eleanor Percival—was after WWI in 1922. This exclusion was rooted in the misconception that women are inherently more emotional and irrational, a belief used both to bar them from medical training and to justify their absence from clinical research

Phoebe Friesen, an Associate Professor in McGill’s departments of Social Studies of Medicine and Equity, Ethics and Policy, discussed this gendered history in an interview with //The Tribune//.

“Traditionally, the notion of hormones disrupting the sort of normal state of a body constantly in a woman’s body was seen as noise,” Friesen explained. “So we have this really again, another sad history where a lot of experiences, symptoms of women in health have been dismissed or have been entangled with stereotypes like an emotional woman, a dramatic woman, an attention-seeking woman, a woman who’s faking it.”

While women are no longer deemed irrational by virtue of their sex, these stereotypes are still dangerously prevalent in medical atmospheres. There are countless recorded instances of women being turned away from medical care with their pain ignored, as doctors—both male and female—have operated under these faulty assumptions. With gender biases so deeply ingrained in medical curricula and interactions in medical schools, all doctors—regardless of sex or gender—are susceptible to undermining concerns expressed by women.

Studies have consistently shown that women receive lower doses of pain medication in the emergency room compared to men experiencing comparable pain levels. The Victoria State Government’s state report on the gender pain gap concluded that 71 per cent of women and non-binary individuals seeking care felt dismissed by their providers.

These stereotypes are particularly dangerous for Indigenous women, women of colour, and women from other marginalized communities. The intersectional nature of oppression compounds practitioner biases, preventing women from getting the care they need. According to a report published by the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in 2019, maternal mortality rates are directly correlated to race: Non-Hispanic Black women had a maternal mortality rate 2.5 times higher than that of white women.

//Getting a (mis)diagnosis//

Women’s enforced absence from the medical sector resulted in male physiology being exclusively studied in medical education, while women were continually excluded from scientific study and clinical trials.

“The history of medical research is just a sad story of the ‘normal’ body being a man’s body,” Friesen said. “So I think it made sense to early researchers, who were primarily men, to focus on the standard male body and utilize them as human participants in research, and it wasn’t until later that people started to recognize how profound the harms were to women.”

This perspective was corroborated by Sara Bishop, a Vancouver-based occupational therapist, who explained how our medical system privileges male symptomatology. When a diagnosis comes before a plan of action, having sex-specific symptomologies is critical to an accurate diagnosis—something our medical system is clearly missing.

“If the diagnostic manual is based mostly on men’s issues and how these issues present to men, then, therefore, some of the symptoms can be missed, because those symptoms are going to present differently in a man versus a woman,” Bishop explained in an interview with //The Tribune//. “But the manual where we, especially doctors, refer to is, I believe, based on men’s symptoms, and so right off the get-go, it’s hard for a woman to get the diagnosis, and therefore the correct treatment that would follow.”

She went on to describe her experience working with people with autism, noting the higher rates of misdiagnosis in girls as opposed to boys. One study showed women are 31 per cent more likely than men to receive an alternate psychiatric diagnosis prior to an autism diagnosis.

“[In girls], autism is often diagnosed as anxiety, depression, or OCD. Girls are given every other kind of mental health diagnosis, and autism is not even considered as a diagnosis,” Bishop said. “It’s treated with antidepressants or anti-anxiety medication, or sometimes ADHD medication, and it’s not helping, and it’s because the real diagnosis is something like autism or some sort of neurodivergency.”

Friesen further explained that, in addition to neurodivergencies and mental health conditions, this pattern of gendered misdiagnoses is prevalent with physical conditions. A salient example is that of heart attacks. Women experiencing heart attacks and other cardiac events are often //sent home// because their symptoms don’t line up with the symptoms //men// display during cardiac events. According to the University of Alberta, 53 per cent of women with heart-attack symptoms are dismissed and left undiagnosed despite seeking care.

This creates a devastating feedback loop, wherein a woman’s pain is not taken seriously, she is sent home without further investigation, and her pain propagates. After being dismissed, women begin to feel discouraged by the lack of support they have received and hesitate to seek out medical care.

“And then also sometimes people, just like in the desperation to be taken seriously, look for their own sort of objective reports to demonstrate their suffering,” Friesen said. “We see people paying out of pocket to get extra blood tests, so that they have something to take in to show, like, ‘look, here’s something real that shows that I’m suffering’ if they’re just continuously being dismissed.”

These extra, out-of-pocket fees add up; in 2023, CNN reported that women in the United States spent approximately $15.4 billion USD more than men, despite ‘equitable’ insurance coverage. This, when coupled with the gender wage gap, showcases just how inaccessible healthcare is for women.

//Forging autonomy//

It was only in 1986 that the U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH) adjusted its guidelines to recommend that women be included as subjects in clinical trials. Since then, the field has been made more accessible. Women can now work in the medical field and participate, both as scientists and subjects, in clinical research.

However, while progress has been made, there is still much work to be done. While women are now studied in a clinical setting, this research is not always done with patients’ consent.

Informed consent is one of the cornerstones of the modern medical system; it is required for participation in any check-up, exam, procedure, or clinical trial. Further, consent critically affirms respect for all persons involved. Yet despite the moral underpinnings of consent, while under anesthesia, women are frequently given pelvic exams without having given prior, explicit consent.

Friesen explained how medical students on OB-GYN rotations are asked to do pelvic exams on anesthetized patients before their surgeries; patients have no way of knowing if these exams are taking place.

“[They are] just using an unconscious body as a teaching tool without [the patient] knowing. And it’s, like, maybe one of the most vulnerable unconscious [bodies], naked from the waist down, faces sometimes covered,” Friesen said. “You don’t need, for the patient’s benefit, several extra pelvic exams by students, who are […] just there to observe.”

Friesen explains that this practice is often defended through claims of ‘students needing to learn,’ however, a desire for education should never override a patient’s right to clear and informed consent. There is no other sector of medicine where consent is breached so clearly and continually. Even //when// women are afforded adequate care, how can we expect them to trust a system that repeatedly violates their boundaries and autonomy?

“Sometimes people talk about ethical erosion in medical school. Just like some things fall away depending on what you learn, often in this sort of hidden curriculum,” Friesen explained. “This is a very implicit lesson about consent, about which bodies can be utilized as teaching tools without consent. And in other cases, you ask for consent.”

//Hear hoofbeats, think horses//

‘Hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras’ is a common refrain in medicine, urging clinicians to pursue the most statistically likely diagnosis rather than a rare one. While this may seem practical, it can have devastating consequences, especially for women.

When providers default to common diagnoses over serious medical concerns, they overlook critical symptoms in favour of simpler, less dangerous, and often inaccurate explanations.

“A lot of things are dismissed from women as anxiety, depression, menopause, and menstrual problems,” Bishop said. “All of these things are kind of considered first before necessarily looking at other diagnoses or comorbidities.”

Treating women’s concerns as inconvenient or routine not only delays proper care but entrenches a cycle of dismissal that prevents adequate treatment altogether.

Gabriella Giorgi, a U3 student studying English and Environmental Sciences, shared her experiences with medical dismissal in an interview with //The Tribune//.

“One time, I had Lyme and pneumonia at the same time,” Giorgi said. “I was very little, but I remember that I was in pain for, like, a year, and [doctors] kept just being like, ‘It’s growing pains.’ And my mom was like, ‘No, like, you need to test her for Lyme.’ And finally, she made them, and I had Lyme, and I had had it for a year. Then [my mom] was like, ‘Can you also test for pneumonia?’ And they [said] ‘No, she just has Lyme. That’s what it is.’ And my mom was like, ‘No, you’re [dismissing her] right now. You said that about Lyme.’ [Meanwhile] I had both of them.”

This was not an isolated incident for Giorgi. Growing up, she suffered from severe stomach aches, with her pain progressing, and further symptoms such as dizzy spells, migraines, and heart palpitations. Yet she was ignored by her doctors when she voiced her concerns.

It was only once Giorgi started //passing out// that she was referred to both a cardiologist and a neurologist. But these specialists, both of whom were male, were no different than the doctors she had seen before: They ignored her concerns, simply chalking her symptoms up to “just anxiety.”

Strikingly, this pattern of dismissal changed as soon as her father—as opposed to her mother—advocated for Giorgi.

“I went back with my dad for a follow-up a few weeks later. And it was very different, like, even just having a male figure there, and they ran, like, a bunch of tests and stuff.”

All it took was having a man voice her concerns, and diagnostic progress was suddenly a conceivable option.

//The prognosis//

Giorgi’s story is not unique. There are innumerable stories of women facing similar circumstances: Women being told they are exaggerating, that they just have anxiety, that their pain is a joke. But women’s pain isn’t the problem; the medical system is squarely at fault.

To be treated, women’s pain first needs to be recognized for what it is: Valid. Women’s symptomatology needs to be understood in its own right, not only perceived through the lens of male presentations, and as Bishop explained, the diagnostic manuals need to be updated to reflect these differing symptomatologies.

“If you’re given the wrong diagnosis, then that leads to the wrong treatment, which takes time away from that girl’s life, where they could be feeling better,” Bishop said. “So if the DSM-5 could be revived, and the studies could be done on girls and women, then that would lead to [a] better diagnostic manual.”

Women need to be heard. Women need to be given the attention and care that men are arbitrarily afforded, and this care must be granted without sacrificing a woman’s dignity, autonomy, or boundaries. It is critical that we continue to advocate for women’s lived experience within the medical system: That we support policies which address healthcare inequities, challenge our own biases about how women experience and express pain, and lobby for consistent application of consent policies in OB-GYN rotations. Medical care must be made equitable for all, and this simply cannot be achieved when women are continually pushed to the periphery of medical studies, practices, and treatment.