Black Canadians, on average, experience disproportionately poor health outcomes throughout their lives. While genetics may contribute to many chronic illnesses and mental health challenges, social and environmental determinants such as limited access to health care and anti-Black racism drive much of this disparity. This discrepancy is compounded by the legacy of colonialism and medical racism, which leaves Black communities underrepresented in mental health research.

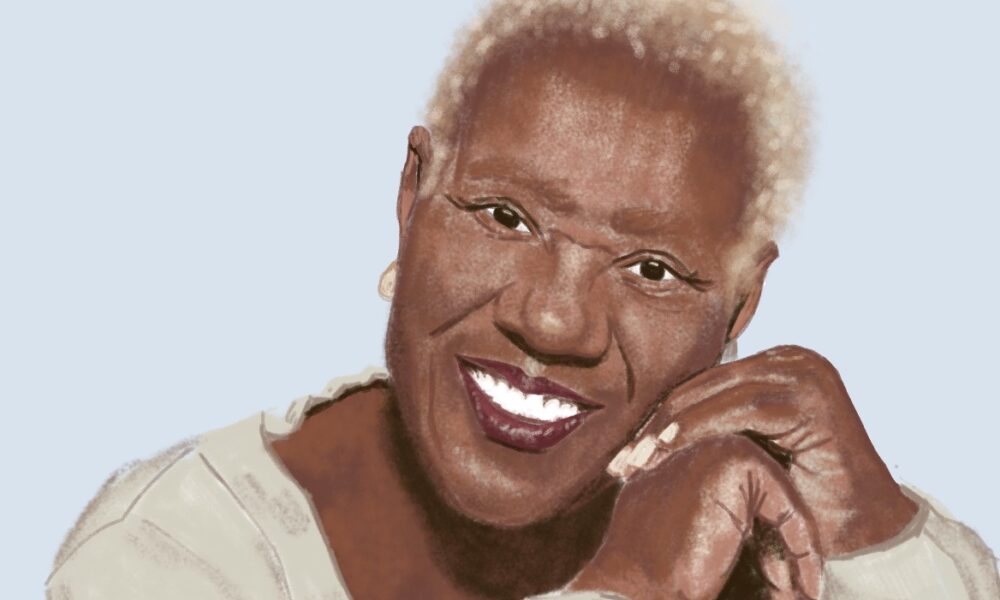

To explore how these inequities affect youth mental health, The Tribune spoke with Myrna Lashley, an associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and adjunct researcher at the Culture and Mental Health Research Unit of the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research.

While researching youth mental health, Lashley noticed that Black youth often carry a profound burden of intergenerational trauma relating to racism while also having to navigate structural racism, shaping how they see themselves.

“Structural racism is based on ideology,” Lashley said. “It’s in our laws, in the way we interact with each other, even in the way we teach religion, in the arts, and cultures, everything, and we have to be very conscious to set things so that Black youth see things that value them as citizens in the Canadian mosaic.”

These systemic pressures also bleed into Black youth’s educational environments. Schools’ anti-violence policies often define violence as solely physical rather than emotional. This results in disciplinary action being taken only against students who respond physically to racial bullying, ignoring the harm caused by racist language. Teachers may also dismiss racist comments or fail to document incidents, leaving frustrated students to undermine their self-worth and sometimes reshape their perceptions of mental health practitioners.

“Anti-violence policy is used against that child, who responded to violence that they have been suffering all along, because violence is often seen only as a physical thing and not as an emotional thing,” Lashley explained. “When you are young, you tend to look at everybody almost the same. So how do you say to somebody, ‘Let’s go and get you some mental health remedies,’ when the person who is going to help you looks like the person that you are angry at?”

Lashley highlighted several persistent barriers in accessing mental health care in Canada for youth, stemming from systemic bias to a lack of culturally competent care and adequately trained professionals.

“We don’t have enough people who understand the issues [.…] You still have people even to this day, who [incorrectly] think that Black people don’t feel pain to the same extent as white people,” Lashley explained. “There are barriers to care in terms of knowledge, there are barriers to care in terms of […] therapists taking racism into the therapy room with them. Have they done the reflection that’s necessary to look at their own privilege?”

In order to offer appropriate mental health resources to Black youth, professionals must recognize their privilege and understand how Black youths are affected by their lived experiences.

“How do you help someone when you already determined that they are genetically flawed as a group? […] You’ve made up your mind that they are aggressive […] You send that kid on the road to difficult mental health issues.”

These barriers often put the onus on Black youth to educate their caregivers or mental health practitioners about their lived experiences, which can discourage them from seeking care. The underrepresentation of Black service providers also leads to lower medical school enrolments within Black communities.

“We’re still in the process of trying to train people to understand not only the lived reality of Black people and therefore […] Black youth, but what effect this has on mental health,” Lashley said. “Because if you feel like you are going to see someone who doesn’t understand you, […] you are spending a bit of money in your first few sessions […] teaching people how to see you. We have to really make sure that when we train people who are working in mental health and are going to help others, that they have a better understanding [of this reality].”

Cultural stigma within Black communities adds another layer of difficulty.

“[There is] stigma within the community, and how we deal with, as Black people, […] mental health, and mental illness. And we are ashamed to have it, so we tend often not to seek the care that’s necessary, and so our youth don’t do it, because we’re not encouraging them to do it.”

Lashley also emphasized how adults’ lack of access to mental health services can create familial and environmental issues that harm children.

“People have to deal with racism in the workplace, and they don’t know how to confront it there, or they have to put food on the table, […] then they go home, and they take it out on the family. The kids get hit, or the partner gets hit, or the person starts to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs,” she said.

With these factors in mind, Lashley shared how she sensitizes professionals and the public to Black mental health through her work.

“I talk with my colleagues, I try not to get angry […] If I’m angry, they don’t hear me [….] When I go to the court, this is what I do: I go to the judge, I give them a history of racism in Canada, not the United States [….] I will talk about it here,” she said.

This ignorance comes from many not knowing their history, placing the burdens of education, which stem from systemic factors, on Black communities themselves.

“A lot of Canadians don’t know their history. And so, I approach it from that perspective and […] have them understand their history so they can understand why […] some Black people don’t trust them. We have to teach our kids that, so that they know how to protect themselves, not to hate you, but for them to protect themselves, and that’s something you don’t have to do with your kids [.…] I get them to address their privilege,” Lashley explained.

Medical and educational institutions also have a role to play in addressing systemic inequities, as they impact not only Black communities but also Indigenous, disabled, and other marginalized populations in various ways. This makes inclusion important in all spheres of life.

“It’s one thing to pull people in, but if you then end up putting people just like polka dots on the background of the hegemony of whiteness, what have you done?”

Looking ahead, Lashley’s work reinforces the need for more research and institutional inclusion to reflect the lived experiences of the studied communities rather than token representation.

“You have to look at the lived experience [….] If you go into a specific group, you have to create what it is you’re studying, the research, with that specific group,” she said. “We can no longer take a position of ‘I am the academic, I know everything, I am going to go and study, and then I am going to impose my results on you.’ That is very insulting. It’s inaccurate, it’s unethical, and it’s unhelpful.”Overall, Lashley stressed the importance of doing inclusive research on mental health in Black youth. She teaches and spreads her expertise not to divide people, but rather to create an egalitarian society where all communities can access the mental health services they deserve without stigma.

“We’re not looking at what divides people [….] We want to know what the issues are. What is dividing people and using that information to pull everybody together [….] We want to create a world, a city, where everybody feels included, and everybody feels equal, and everybody is getting equity.”