Monica Colín Silva and her family moved to Quebec City from Mexico four years ago, during which she obtained a Master’s degree at Université Laval. After completing the program and becoming fluent in French, she felt hopeful for her path to permanent residency in Quebec.

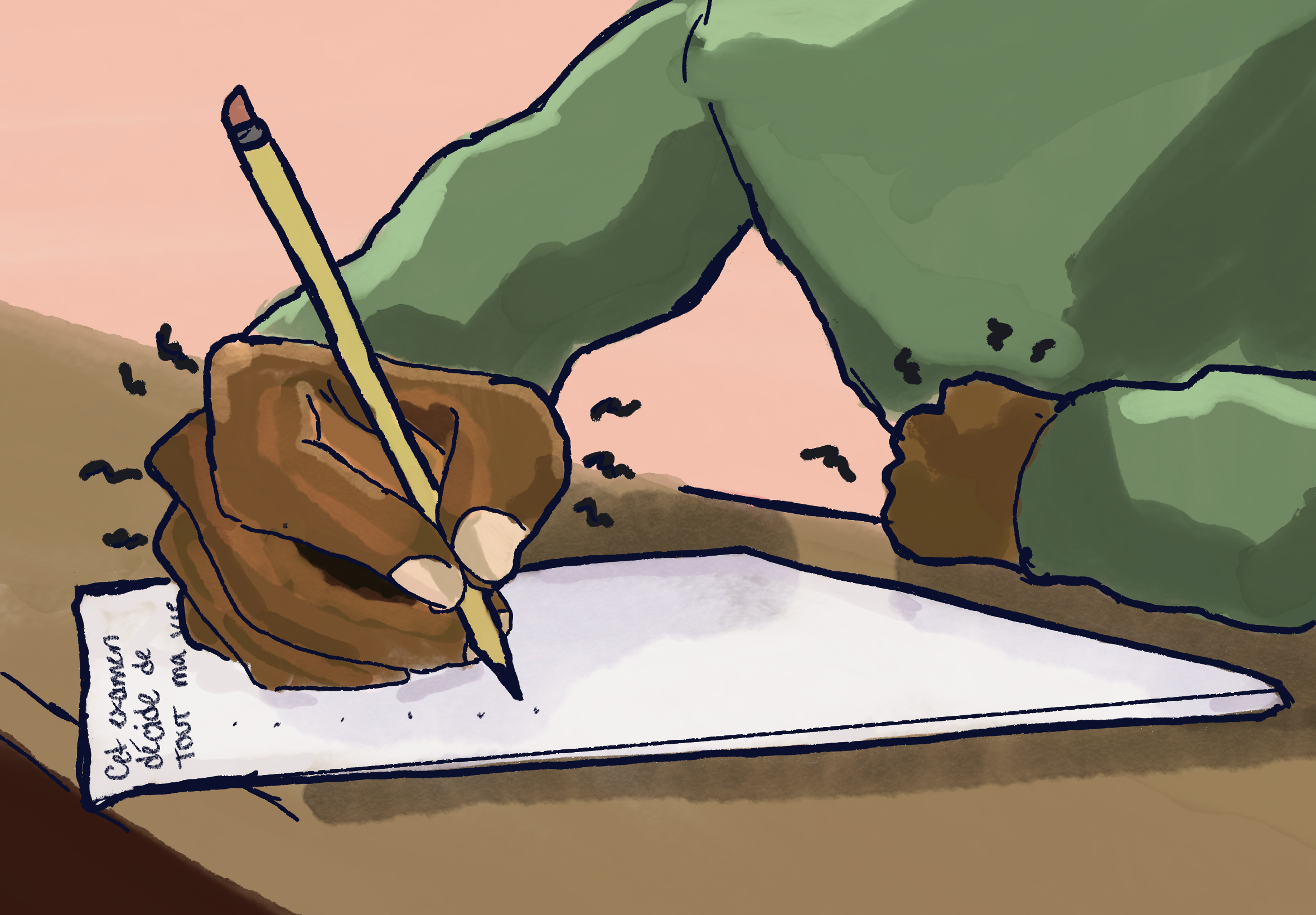

In late 2024, the federal government started requiring post-graduation work permit applicants to take a language test. Colín Silva’s score of 427 on the written section of the required French exam fell one point short of the minimum 428 threshold. Because the permit is directly tied to the applicant’s authorization to work, Colín Silva’s failing score meant that neither she nor her husband would be eligible for employment in Quebec. Facing limited options to support her family, Colín Silva is preparing to return to Mexico.

While framed as measures to protect Quebec’s linguistic and economic priorities, these reforms place educated international graduates in a state of uncertainty, where years of academic achievement and language acquisition are undermined by shifting immigration policies.

The stricter language requirements are just one example of controversial policy changes made to Quebec’s immigration system under Immigration Minister Jean-François Roberge this year. In September 2024, the government replaced the Quebec Experience Program (PEQ) with the new Skilled Worker Selection Program (PSTQ), shifting to a points-based system that evaluates applicants across several categories to determine how strongly they “match Quebec’s needs.” Roberge has argued that the new program allows Quebec to select workers in the sectors it considers most valuable, such as healthcare, education, and construction.

The PEQ’s dissolution has left thousands of international students, along with countless professors and other academics in Quebec, feeling suddenly abandoned, as it is almost impossible to predict one’s chances of being approved under the PSTQ. The point system leaves much to the government’s subjective interpretation of the value of one’s job instead of providing a clear checklist for hopeful applicants.

29.8 per cent of McGill’s student body of over 40,000 is made up of international students—and for many, repeated shifts in immigration policy can generate uncertainty around their chances of a future in Quebec. Quebec’s universities rely on international students for tuition and academic contributions during their studies, but its evolving immigration framework has made long-term settlement far less predictable once those students graduate.

For students like Colín Silva, the inherent issue lies not in Quebec’s desire to preserve French, but in how narrowly immigrants are defined under the law. When one score on an exam outweighs years of living, studying and working in French within Quebec’s institutions—including the completion of a Master’s degree in the language—it calls into question whether the current paths to permanent residency are fairly and holistically evaluating applicants.

Besides increased scrutiny on an applicant’s field of work, Quebec’s updated permanent residency pathways now require graduates to have completed at least three years’ worth, or 75 percent of their coursework in French, in order to qualify. For students who began their studies under previous criteria, the change has caused great anxiety, particularly for non-Francophone university students, as they now struggle to make up for the French coursework they’re missing.

When single factors such as line of work or language policy become the determinant in deciding who gets to stay and who must leave Quebec, the province sacrifices the minds of countless talented individuals whose stories, if considered through more holistic measures, would more than demonstrate their eagerness and dedication to contribute to the province’s workforce. While Quebec has the right to protect French and its cultural identity, rigid criteria excludes many graduates with proven intentions of contributing to Quebec in the long term. Colín Silva’s story demonstrates that she belongs in Quebec, and that the value her family can offer Quebec cannot be reduced to a single point on a standardized exam.