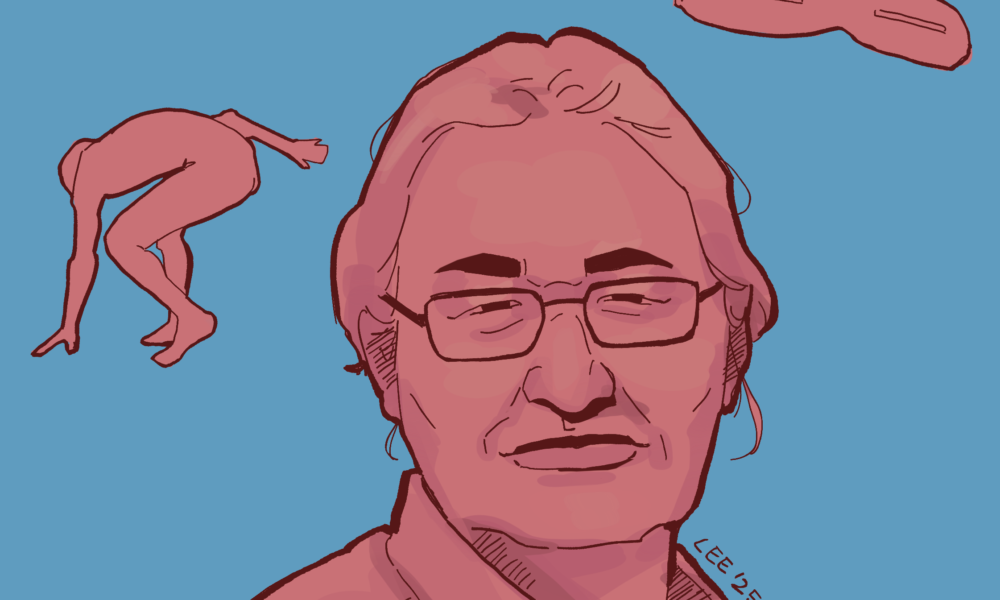

At the Toronto International Film Festival on Sept. 14, Inuit filmmaker and co-founder of Isuma Productions, Zacharius Kunuk, received the Best Canadian Feature Film Award for his latest work, Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband). This award recognizes his career’s continued influence—defined by innovation, community, and cultural reclamation. Over two decades after his 2001 hit film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, Kunuk once again reclaims myth from the colonial lens, showcasing Inuit life in all its cultural richness. He asserts that Indigenous life is not an archaic history to be caricaturized, but that it belongs to a present and future to be expanded on in Indigenous pop culture.

Uiksaringitara carries this narrative forward, using its plot to intertwine themes of survival, personal struggle, familial ties, and spiritual guidance into mythology. The film opens with a promise of two young lovers, Kaujak and Sapa, pledged to one another at birth. Their relationship is split apart when Kaujak’s mother remarries after her husband’s death, forcing Kaujak into another camp. She sets out on a journey to find Sapa, guided by spirit helpers, blurring the line between physical and mythical.

Uiksaringitara also captivates its audience by combining authenticity with imagination. It pushes against Hollywood’s reductive portrayal of Indigenous characters through its careful casting. The film’s cast consists almost entirely of new Inuit actors, allowing community dynamics of traditional narratives and spiritual practices to shine through naturally, rather than be distorted by old Hollywood conventions. His film is not to be examined through the Western lens; shamans and spirit guides are reflections of Inuit cosmology, not metaphors to be critiqued. This intention of creating community, rather than international critical acclaim, is a sentiment reflected by many contemporary Indigenous filmmakers.

Kunuk is not working alone in his reclamation of the screen—he is part of a larger scheme in contemporary Indigenous media. Wapikoni Mobile is a Montreal-based travelling film studio that works with Indigenous youth across Québec and Canada. Their short films construct narratives of everyday life, joy, humour, and continued resilience, despite the harmful stereotypes imposed on them by film history. Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin contributes to this larger movement as well, using film as a political tool. In her 1993 documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, she depicts the events of the Oka Crisis through an Indigenous lens. Her work dismantles the harmful narratives perpetuated by Canadian media, which have often portrayed the Kanehsatake people as violent aggressors.

In Uiksaringitara, Kunuk’s attention to detail, evident in his use of language, extends to his visual portrayal of Inuit culture. During the filmmaking process, he consulted elders to ensure accuracy in all aspects, notably in the costume department. Their deep knowledge contributed to the rejection of stereotypes through a hands-on approach, as they taught the younger community sewing traditions. The costumes in Uiksaringitara are handmade from caribou and sealskin, using methods of Inuit clothing tradition. Every aspect of these films is reconstructed with painstaking care, not as static museum pieces, but as living things. Compared to old Hollywood’s mocking costumes of fringe jackets and cowboy clothes, the contrast is stark.

Kunuk’s work also revives the Indigenous tradition of oral history, giving voice to Inuit culture for future generations. Both Atanarjuat and Uiksaringitara are filmed entirely in Inuktitut, with the former being the first Canadian film produced entirely in the language. Québecers in particular know the power of language in preserving culture and building identity. Yet, this urgency rarely extends to the Indigenous languages spoken here long before the arrival of French or English. Their language is not a relic of the past, but a living vessel of culture and identity.

Kunuk and his peers do more than fight stereotypes: They transcend them. Uiksaringitara creates an art world where Inuit audiences see themselves not as exotic relics, but as protagonists. This is art made first for the community, and then for the world. Kunuk writes Inuit life into the present tense, claiming the screen as a space of belonging, imagination, and cultural sovereignty.