Wes Anderson is widely distinguished for his aesthetic style—features ranging from striking symmetry to eye-level points of view, pastels to vibrant hues. Highlighting ordinary objects in otherwise distinctive ways, viewers have even begun to excavate these aspects in their everyday lives. @Accidentalwesanderson on Instagram has amassed nearly two million followers, featuring photo submissions that echo cinematography seen in Anderson’s films. However, as his audience continually praises his work for its visuals, does Anderson risk relying solely on aesthetics?

The Phoenician Scheme, Anderson’s most recent film, tells a simple tale of a jaded tycoon confronting the reality that one day—and very soon—he will die. The film begins poignantly, featuring cinematography and colors reminiscent of a stereotypical Coney Island, with expressions almost straight from a stop-motion animation. Within the first five minutes, the protagonist, Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), survives a plane crash: His first near-death experience of the narrative. With an abrupt shift from Anderson’s typical retro and pastel coloring, the film skips ahead to a Lynchian-style purgatory. Now, in black and white, Knave (Willem Dafoe) materializes, sporting an overgrown, darkened beard within a clouded backdrop, a side character whose sole purpose in the narrative seems to be to provide a sense of turmoil and unrest.

Following his first flash of purgatory, Korda reaches out to his only daughter of ten children, a nun named Leisl (Mia Threapleton), to take over his business in the likely case that he gets assassinated. Sister Leisl acts as a symbol of hyperbolized purity, providing a stark contrast to her father and ultimately cheapening an already plain plot. In the scene, Korda is seen ruthless, covered in blood, staggering about while holding his guts in. In comparison, Leisl arrives head-to-toe in white, adorned in a bright red lipstick that matches her lengthened nails. Anderson is known for characters who are stylistically cartoonish and poignant, but in The Phoenician Scheme he fails to write his characters beyond aestheticism. Leisl is an esoteric Halloween costume at best.

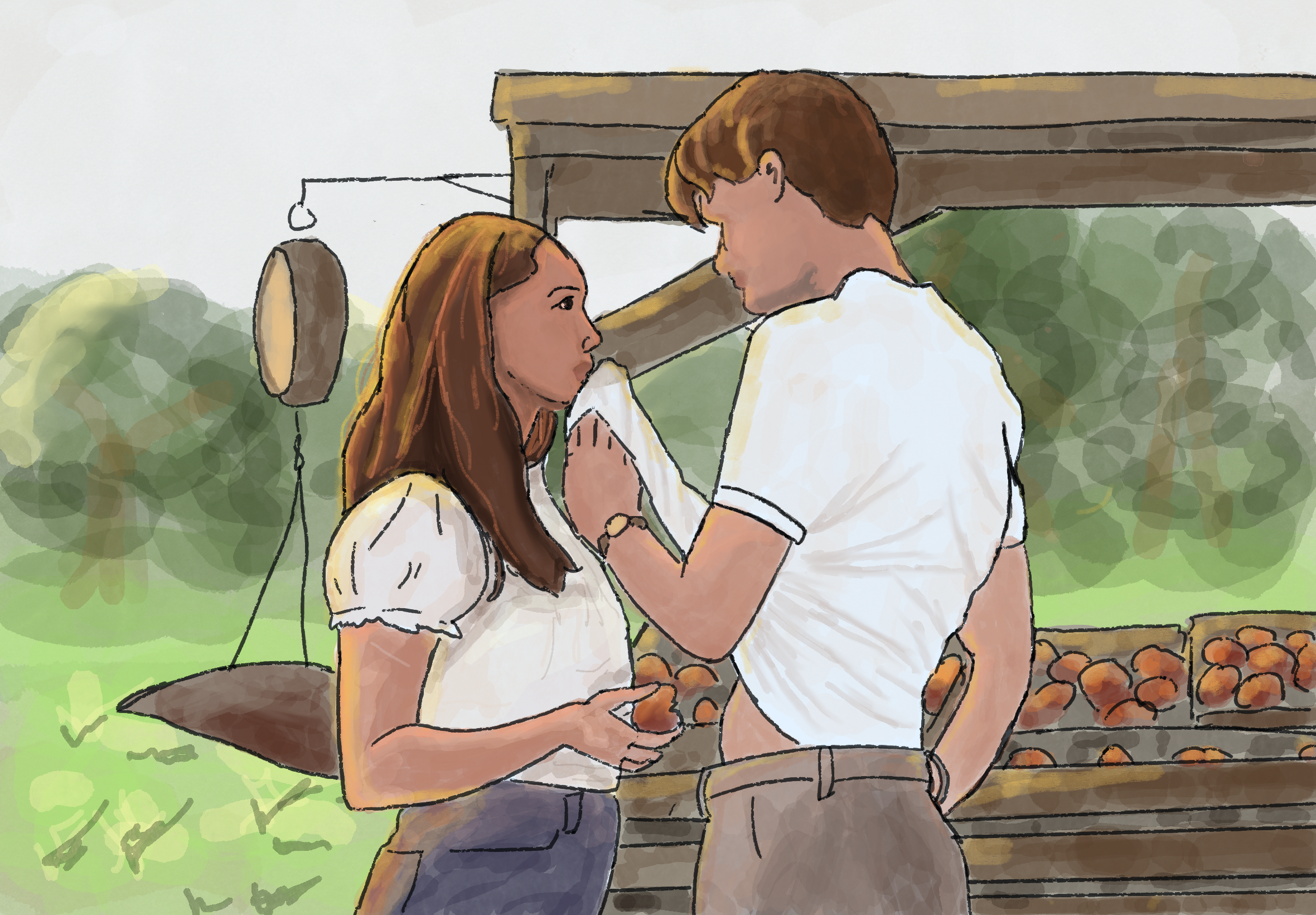

As the film progresses, her morals quickly crumble. At the first sign of conflict, she whips a knife out from under her habit, one she says she picked up right before they left for the venture. When offered a beer, she promptly says she has never had hard liquor in her life. Korda’s assistant, Bjorn (Michael Cera), reminds in his Norwegian accent that beer is not hard liquor. Without skipping a beat she turns to the waitress: “Two beers please.” She soon picks up pipe-smoking, eventually switching out her plain, white pipe for a bejeweled one. The ease with which she is convinced to sacrifice her morals feels parallel to asking your alcoholic friend to have a drink: “Okay, fine, I guess I’ll go out.”

The film is hilarious—but it is not profound, no matter how hard it tries to come across as such. The viewer understands that life cannot be separated into good and bad, so what else? As the film continues, those binaries flatten. The tycoon and the nun meet each other in the middle, at the sea level of morality. Anderson shows us that a nun can wield a knife and a murdering tycoon can adopt catholicism, reducing the film to a shallow cliché.

Beyond diving into—or skimming—the grey area between morally superior and inferior, and the confrontation of what makes the balance tip in either direction, The Phoenician Scheme lacks any unique take on an overused theme. The Phoenician Scheme is neither extraordinary nor horrendous, but the grey area between the two: Mediocre.