The McGill Department of Family Medicine’s Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion Committee hosted a seminar titled ‘Queer History Month: Inclusive Language Awareness’ on Oct. 28. Family Medicine graduate students Brigitte Durieux and Joshua Ramos presented the seminar in which they discussed the importance of inclusive language, emphasizing its vitality in professional and academic spaces.

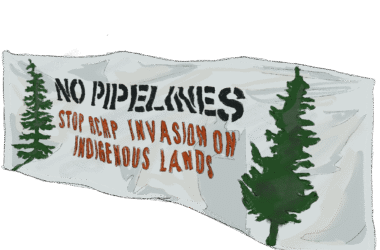

The event coincided with increasing debates over inclusive language in Quebec. Earlier this year, French Language Minister Jean-François Roberge introduced legislation banning the use of gender-neutral inclusive language in all government communications. This policy has raised concerns among 2SLGBTQIA+ advocates and others who see inclusive language as crucial to visibility and respect. The Family Medicine Department’s seminar aimed to reaffirm that language is not just a policy issue, but one that affects the everyday lives of queer people.

Brigitte Durieux, a second-year graduate student in the Department of Family Medicine, presented the first segment of the seminar. They stressed the importance of respecting people’s pronouns, even if they appear unfamiliar or confusing.

“You don’t need to deeply understand or relate to something to respect its existence,” Durieux stated. “So it’s okay to be confused if you meet a new person and they use pronouns you’ve not heard before. It’s hard at first. It’s okay as long as you’re trying.”

Durieux went on to provide brief historical context on the treatment of 2SLGBTQIA+ people, discussing how systems of power have historically defined what is considered ‘normal’ or ‘acceptable,’ often marginalizing queer identities.

“Most queer people in most places have experienced some sort of power structure that ensures its own viability over time through identifying a correct way to live, [either] explicitly or implicitly through the way people socially treat each other,” Durieux explained. “In many places, it’s very illegal for sex between men to take place. This is usually related to religious texts and arguments about nature, despite the fact that homosexuality is naturally occurring.”

The seminar proceeded with a segment from Joshua Ramos, another graduate student in the Department of Family Medicine. They presented an overview of some theoretical frameworks of feminist and queer theory.

“There is no single feminist theory. Feminist theory can be considered a family of critical theories and approaches,” Ramos stressed. “Queer theory, [a term] coined by Teresa De Lauretis, is a critical approach to challenge norms and inequalities related to sexuality and gender. De Lauretis saw queerness as a way to understand sexuality and gender as fluid, socially-constructed concepts that enact resistance to dominant cultural and institutional powers.”

While Durieux and Ramos’ presentation emphasized the academic and theoretical dimensions of inclusive language, campus advocacy groups at McGill are also pushing for a broader cultural shift. In a written statement to The Tribune, Queer McGill’s administrative coordinator Val Munoz emphasized that Roberge’s bill is an example of how language can be used to limit rather than empower.

“[Roberge’s language] ban is deeply concerning because it reinforces the idea that inclusivity is optional, something to be regulated rather than lived,” Munoz stated. “It also exposes how language and power are intertwined. By restricting how we can write or speak, the government is effectively restricting how we can think about gender. The French language’s rigid gender binary is already a barrier for many queer and trans people, and policies like this deepen that exclusion.”

Munoz concluded by highlighting the significance of linguistic inclusivity as a way to enact positive social change.

“Language is powerful; it can either liberate or silence,” they wrote. “True and critical allyship means recognizing that inclusive language is not about political correctness but about survival, dignity, and recognition [….] During Queer History Month, and beyond, I hope the McGill community reflects on how language shapes whose histories are celebrated and whose are erased, and chooses to speak in ways that affirm, rather than diminish, our existence.”