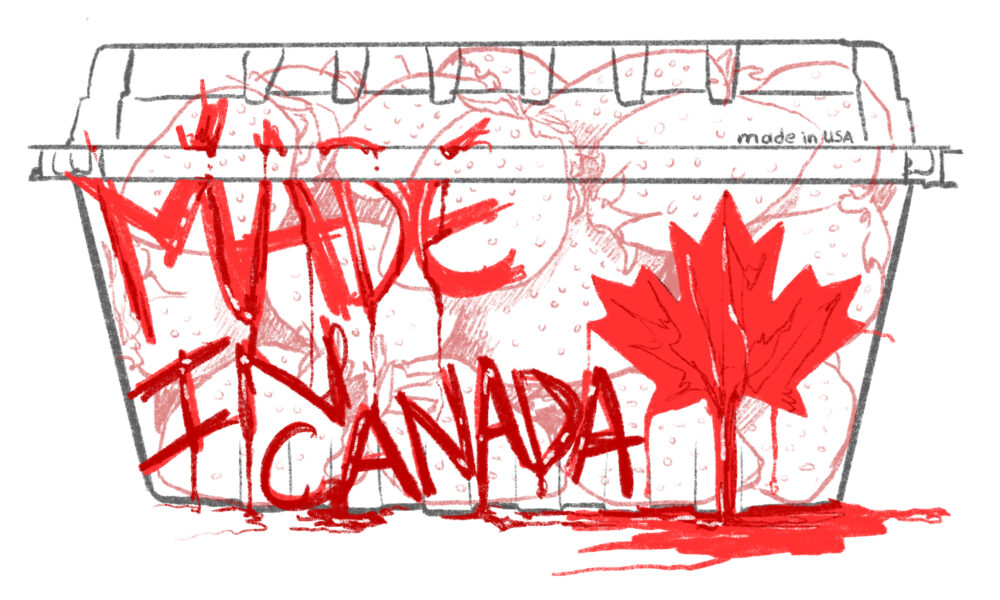

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) confirmed 12 cases of ‘maple-washing’ between February and May 2025, a marketing tactic that exploits Canadian patriotism to encourage sales of imported goods. The agency caught multiple grocery chains promoting non-Canadian products using “Product of Canada” and “Made in Canada” labels, as well as a maple leaf symbol, thus threatening consumer trust, harming local businesses, and disadvantaging the domestic market in the process.

The CFIA can fine offenders up to $15,000 CAD when they jeopardize access to Canadian goods on the market. Yet, the agency issued no fines over the recently observed cases of maple-washing, despite their clear violation of Canada’s advertising laws. The CFIA’s reasons for the lack of fines stay vague; it states that labels had been corrected and issues therefore settled. Grocers receiving complaints have tagged false labelling as mere errors—and the CFIA seem more than willing to ignore the corporations’ plausibly calculated intentions.

However, incidents of false advertising deemed ‘simple mistakes’ have not gone away nor settled following the issuance of complaints. In fact, maple-washing saw a recent increase: The CFIA observed more than 70 complaints in July and August. Maple-washing’s rise in prevalence represents a strategic ploy by non-Canadian corporations. As Canadians attempt to promote the domestic market amidst tariff disputes and tensions with the White House, maple-washing offers a sly way to boost sales of boycotted imported goods.

President Trump’s reiterations—in March and June—of his wish to colonize Canada as the U.S.’ 51st state, combined with new 35 per cent tariffs on Canadian goods implemented on Aug. 1, galvanized Canadians into promoting domestic industry. The ‘Buy Canadian’ movement emerged as consumers began to prioritize buying local: 45 per cent of Canadians state they actively boycott U.S. goods in response to tariffs, choosing instead to purchase Canadian substitutes. McGill students shopping around campus at Provigo and Metro may have been impacted by maple-washing, as they have an incentive to buy Canadian as a statement against Trump’s policies.

Aware of these changes in consumer preferences, corporations have used maple leaf logos or “Made in Canada” labels to avoid market share decline. Riding the wave of Canadian patriotism to promote international products is a clever marketing strategy. However, it becomes an unethical one when companies weaponize nationalism for profit by lying to their customers about their products’ country of origin.

The CFIA led a four-month investigation against Canadian grocery store Sobeys over imported avocado oil marketed as “Made in Canada,” but closed the case without issuing any penalties. The CFIA’s failure to act on recognized maple-washing pushes aside customers’ concerns and rights to accurate, truthful advertising. Consumers who have reported maple-washing cases say grocers have eroded their trust and demand punishment for misleading marketing patterns.

Montreal lawyer Joey Zukran took matters into his own hands in mid-September by seeking court approval to sue Provigo, Metro, and Sobeys, among other companies. After witnessing the CFIA’s inaction, Zukran aims to show that systemic false advertising cannot go unpunished.

As a result of maple-washing, Canada is losing an opportunity to benefit from its tariff war with the United States. By fearing a loss in capital, corporations have selfishly squandered Canada’s chance to capitalize on nationalistic momentum transparently and without threatening long-term market development. Instead, local companies remain overshadowed by imported goods even when citizens express a strong commitment to strengthening the national economy through their individual consumption choices.

Labelling inaccuracies, when recurring and consistently made by multiple commercial corporations, are not mistakes. Companies falsely promoting products as Canadian should suffer a penalty: Normalizing incorrect labelling allows misleading advertising to secure its position in the food-selling industry. Until fines follow from fraud, the maple leaf risks regressing from a national emblem to a mere marketing gimmick.