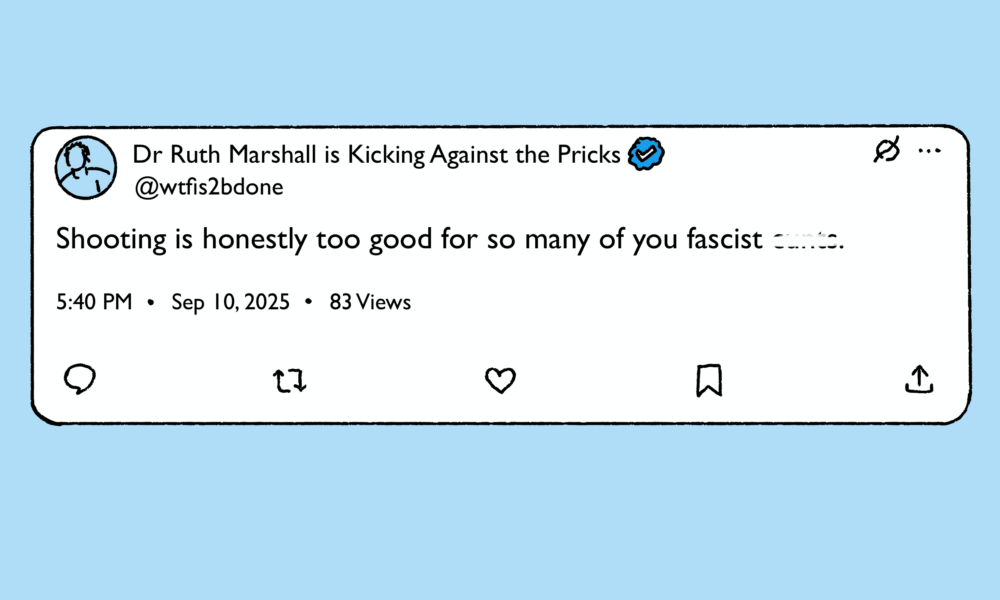

At 12:23 p.m. on Sept. 10, far-right activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated in front of a crowd of 3,000 at Utah Valley University. An hour and 20 minutes later, Ruth Marshall, a professor of religious studies and political science at the University of Toronto (UofT), tweeted: “Shooting is honestly too good for so many of you fascist c**ts.” Because of this tweet, UofT placed Marshall on leave and opened an investigation into her actions. If she is found to have caused UofT ‘reputational harm,’ Marshall may be terminated. This respect for procedure is commendable, but Marshall’s tweet demonstrates that she should not be a university professor and justifies her immediate firing.

It is important not to conflate Marshall’s suspension with other instances of censorship following Kirk’s death. The Trump administration has used the event as justification to attack and silence its political opponents, casting all criticism of Kirk or his movement as ‘hate speech’; unsurprisingly, no such move was made against far-right groups following the murder of Minnesota Democratic lawmaker Melissa Hortman in June.

However, in Marshall’s case, her words were neither justified nor defensible. She was not criticizing the administration’s actions or Kirk’s views: She was calling for further violence. That is a line that should never be crossed in political debate.

In her tweet, Marshall calls Kirk a fascist, which he was. Kirk described all undocumented immigrants as “would-be rapists” to justify shooting them; he said that gay people wanted to “corrupt children,” a well-known homophobic dog-whistle; he implied trans women should be lynched. Kirk’s arguments were also frequently based on conspiracy theories: He famously denied the validity of the 2020 election. Such disregard for truth and democracy, along with blatant normalization of violence, is the foundational material on which fascist movements are built. But before it is a movement, fascism is a rhetoric that claims: Some lives are worth less than others. Some people deserve to be killed. Marshall’s tweet espoused that rhetoric.

It is common these days to hear that free speech and open diversity of opinion are integral to universities and to society as a whole. It is true that society cannot progress without debate. However, proper and productive debate is not ritualized ‘destruction’ of ‘opponents,’ but rather honest discussion between good-faith parties with the aim of learning and moving forward towards a better reality for all.

Some things, however, are not up for debate. An opinion that justifies violence as a means to a political end is not worth platforming: It intrinsically rejects dissent, and so it is antithetical to the mission of universities. Charlie Kirk was killed on the campus of Utah Valley University while promoting violent views. He should not have been invited to the campus at all. Ruth Marshall, having projected similarly violent opinions, should not be allowed on UofT’s campus.

It would be naive, of course, to claim that Marshall’s deviation from proper and respectful debate was the actual reason for her suspension. Earlier this year, Marshall herself rightly called out UofT for failing to formally condemn professors using similarly violent language against pro-Palestinian protesters and journalists.

Rather, UofT may have had much more pragmatic reasons for sanctioning Marshall. On the right and far-right, Kirk’s death has prompted explicit talk of war and revenge. Tweets celebrating the murder could reasonably be expected to provoke violent retaliation against Marshall’s colleagues, her students, and herself. UofT has not publicly stated its reasoning in sanctioning Marshall. After her suspension, however, UofT blocked public access to her department webpage, which presumably contained information on the location of her office. On Monday, the building where she works was closed.

One of the great successes of liberal democracy has been unprecedented safety from political violence. Before the late 20th century, most of our ancestors lived in dread of brutal, arbitrary attacks. Free speech is fundamental to preserving this achievement—but only when it serves discourse rather than destroying it. The moment we use our freedom of expression to call for violence against our political opponents, we abandon the very principles that make free speech worth defending. Universities, as guardians of open inquiry, have both the right and the responsibility to draw this line.