Electronic cigarette usage has increased rapidly in recent years, with global estimates surpassing 100 million users. As vaping continues to grow in popularity, physicians and public health researchers are facing a difficult question: How should people quit a habit for which there is virtually no medical treatment consensus? A new clinical research review suggests the answer may already exist.

Tamila Varyvoda, a first-year student in McGill’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, found that varenicline—a medication prescribed to help people stop smoking cigarettes—may also help users quit vaping. The drug appears safe and potentially effective, though scientists emphasize that evidence is still developing.

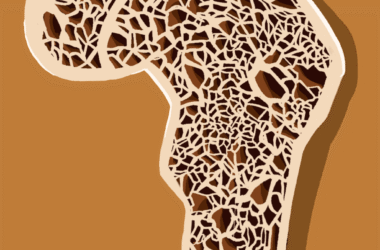

Although vaping is often marketed as a safer alternative to smoking, it still administers nicotine, a substance that creates addiction by stimulating reward pathways in the brain. Despite growing concerns about its effects, there are no medications specifically approved to treat vaping dependency.

“Historically, teenagers were introduced to nicotine through cigarettes,” Varyvoda said in an interview with The Tribune. “Now that’s no longer the case. The first thing many young people try is vaping. When I was in CEGEP, there was literally an entrance where everyone would stand and vape. Seeing that made it clear that if we’re going to help people quit nicotine addiction, we need treatments designed for this new reality [….] If there’s a time we need treatments to help people quit, it’s now.”

Researchers are intrigued by varenicline because, although it is typically used to help cigarette smokers quit, it is suspected that the medication could work for e-cigarette users as well. Varenicline targets the same brain receptors as nicotine, partially stimulating the receptor while blocking nicotine’s full effect, and thus maintaining a moderate dopamine release that reduces cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

To investigate this hypothesis, Varyvoda conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, combining the results of three randomized controlled trials conducted between 2023 and 2025 in Europe and the United States.

Across those trials, 178 participants received varenicline while 177 received a placebo. Participants ranged in age from roughly their early twenties to mid-fifties, and about half were male. Treatments lasted between eight and 12 weeks, and participants were followed for up to 24 weeks. In addition to medication, many participants also received behavioural support such as counselling sessions or text-based quitting programs.

Researchers measured success primarily by whether participants stopped vaping. Results showed that people taking varenicline were estimated to be about twice as likely to achieve abstinence as those receiving a placebo, although the limited sample size prevented any statistical significance.

“We couldn’t say, in good conscience, that varenicline was definitively effective yet,” Varyvoda explained. “Two of the trials showed clear benefits, but a smaller pilot study was inconclusive, which widened the confidence interval. Larger studies with longer follow-ups will likely clarify the effect, but right now the evidence points in a promising direction rather than a final answer.”

Stronger evidence appeared in secondary measures. Participants using varenicline were more than twice as likely to report not vaping within the previous week, both at the end of treatment and during follow-ups. In two of the trials, continuous abstinence rates reached roughly 40 to 51 per cent in the varenicline groups compared to about 14 to 20 per cent in placebo groups at the end of treatment and remained higher months later.

Safety findings were reassuring as well. Serious adverse reactions occurred in zero to three per cent of participants. The most reported side effects included nausea, insomnia, and vivid dreams, which were typically mild and temporary. Overall, the drug did not produce a higher rate of serious complications compared to the placebo.

Varyvoda reiterated that evidence remains limited. With only three trials available, and one involving only 40 participants, the results are not necessarily conclusive. Differences in treatment length and how quitting was measured also reduced certainty in the findings. In any case, Varyvoda reminds us that quitting nicotine is a path worth pursuing.

“It’s never too late to take care of your health,” Varyvoda said. “Quitting nicotine is difficult, but the body can recover, and it’s always worth trying.”