Dyskinetic cerebral palsy is the second most common subtype of cerebral palsy (CP). Children with DCP usually experience serious motor impairments along with comorbidities such as cognitive deficits, communication challenges, seizure disorders, and sensory impairments.

Despite its severity, very little is understood about DCP. McGill MD student Victoria D’Amours and her colleagues, representing prominent pediatric institutes across Canada, attempted to address these critical research gaps by conducting a large sample study on DCP, which was published in Pediatric Neurology.

“People tend to believe that cerebral palsy is just associated with a baby that lacked oxygen at birth. But actually, that’s not it,” D’Amours said in an interview with The Tribune. “You have kids that grew up without CP and can develop CP as long as there is a certain insult to the brain. And to know there are certain factors that can either cause or increase the severity of cerebral palsy.”

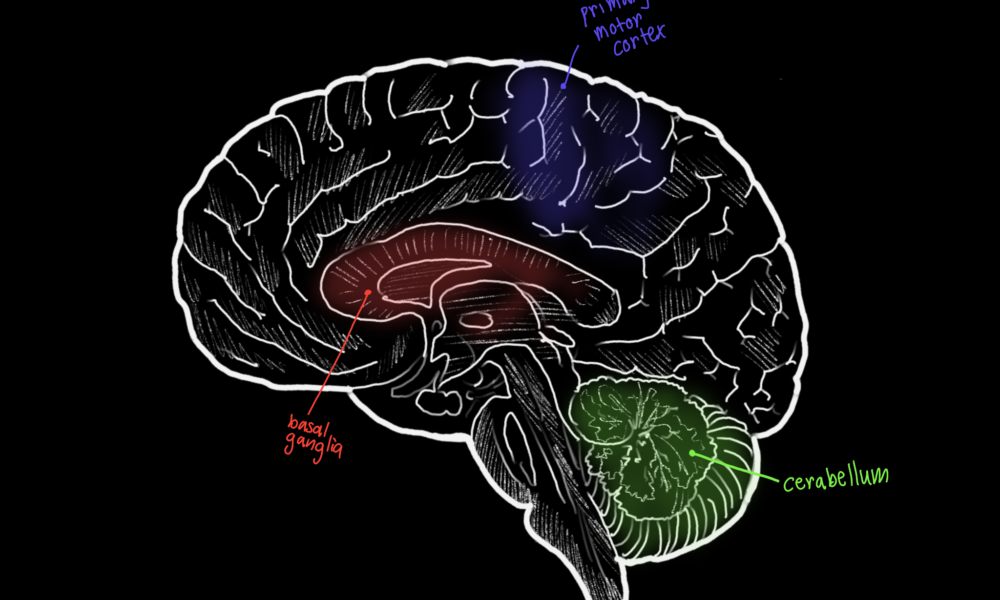

In their study, D’Amours and her colleagues evaluated the prognostic significance—how much a particular factor can be used to determine the outcome of a disease or disorder—of two potential early markers: Gestational age (GA) and neonatal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. GA is the time period between conception and birth, whereas neonatal MRI involves scanning a newborn’s brain to detect any abnormalities. Both methods are routinely available in early life care and have been proposed as predictors of developmental outcomes in other forms of CP, yet their use in DCP remains under-researched.

D’Amours’s analysis draws on data from a sample from the Canadian Cerebral Palsy Registry of 170 children diagnosed with DCP. This study’s large sample size is especially vital considering that the majority of previous research on DCP used relatively small convenience samples.

D’Amours and her colleagues compared the effectiveness of GA to MRI as early indicators of DCP. Based on their findings, they concluded that GA analysis was a more effective indicator for properly diagnosing DCP. Specifically regarding GA, D’Amours found that 60 per cent of the infants with DCP included in the study were born at term.

“I don’t think MRI is necessarily inconclusive. I just think when we do compare MRI to gestational age, gestational age is a better predictor of future DCP severity,” D’Amours said in an interview with The Tribune.

These results could help alleviate the delays in diagnosing DCP in children. If certain patterns of brain injury from MRI or thresholds of maturity in GA are found to reliably predict worse outcomes, then children exposed to these methods might benefit from earlier diagnoses and more intensive support. This could, in turn, help to improve the overall quality of life for children afflicted with DCP.

Although D’Amours’ work provides tremendous insight into this subtype of cerebral palsy, DCP remains a critically underexplored subject. Researchers have yet to understand why children born at term are more likely to have DCP than others. Investigating the root causes of DCP is the next step in uncovering these mysteries.

“We found that there are more kids with DCP that were born at term, but we also don’t know why,” D’Amours said. “So I think the future is in digging deeper and understanding the causal relationships between things, and also seeing where genetics actually plays a role.”