In 1974, the first Black woman Random House editor gathered photographs, sheet music, advertisements, obituaries, patent applications, materials, art, and ephemera in a collection entitled The Black Book. These archives, anthologies, collages, and scrapbooks celebrated, bore witness to, and captured the spectacular and the quotidian of Black life in all its forms since the so-called United States founding, all in one. Of, by, and for us––two scripts run parallel, knowing their touch, their fraught point of intersection is tender, causing blood and ink to spill. How could this publishing house make legible histories, performances, and comings-into-being of Blackness without minstrelizing, over-disclosing, running foul of the secrets we’ve kept for ourselves across generations––shared in the quiet moments of collective grace?

I (once again) heard about Toni Morrison’s editorial pursuits in this endeavour in the Leacock Building, for a public talk. As one of few Black attendants, other than the speaker, my walk to the building passed the Arts Building’s steps. A gateway to the humanities that stands in front of the violent memorial to our namesake who slumbers peacefully, with no regard for his enslavement of Indigenous children and Black people. The haunt of our ancestors hangs in his wake, Black life, labour, aliveness, solidarity, at the place where margin erupts into the centre; for to be advertised is to be remembered. By work all things increase and grow.

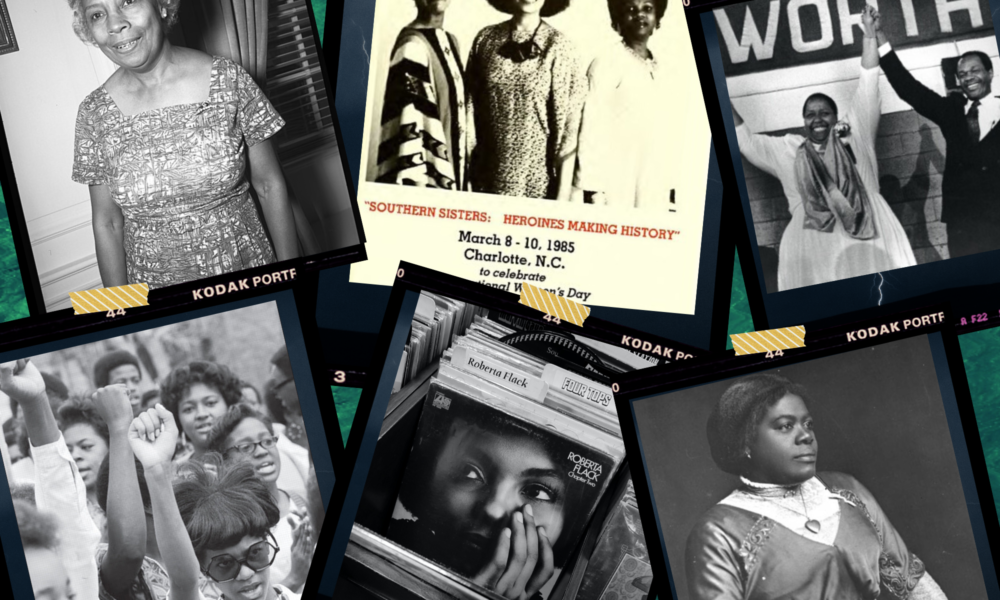

How do we commemorate lives and ourselves outside of the popular modes of redress, commissions, public declarations; the plans, lists, records, books, numbers, and names made available? The Tribune sat down to articulate practices of counter-archives, archives that feel, that glint with golden futurity, that hold the muck and mess of the past and acknowledge the inaccessible dimensions of what we consider to be the standard archive.

Forging the ephemeral

When we think of archives, or extracting from archives, the image we construct are thick stacks, sign-up sheets manned by an agent with extraordinary discretionary power, silence, clubs that not all of us can join (they scattered the ashes and went). What would it be to say the informal archive might be loud, clamoured by voices chanting, singing, screaming, guiding, fostering, choking, or not always tied to the institution? Your memories matter because you studied at an international institution, shielded from the fall, and actively manufactured death.

Think about the amorous, nebulous glance from a potential lover, the nod from a comrade, the modes of social organizing and policing that attempt to strip Black and Indigenous people, women and queer and trans people of colour from spreading the unspeakable for revolution, the contact points that touch softly in times of peace and war. The photos, the laughs, the stillness of wandering in a time outside of the clock.

The art of losing’s not too hard to master. Write it! Scribble on the peripheries. Avoid the malconstructed public demands that impede your privacy. Our lives depend on the extraordinary within the ordinary practices of remembering, seeing, thinking, and living with each other differently.

Archiving with each other

The private is ripe with offerings to transform our public accounts of memory practice. Activist-author-organizer-researcher-librarian-abolitionist Mariame Kaba reminds us to move beyond carcerality and policing in the blooms only a library could gift us. We must navigate the violence that asks us to remember when our media circulates photographs of Black death and suffering, violence against refugees, Indigenous peoples, women, girls, and Two-Spirit people missing in the favour of white sentimental global uplift. No apologies without structural transformation should be accepted.

The question endures––what can the library, the more formal archive, build from this? Our communication, cryptic and coded, must work to a critical consciousness. Radical library practice means opening up doors, placing value on the democratic need to sit, to recover, to evade the seemingly insuperable burdens of in the cracks of underfunded social institutions. Sharing what we have, the books, the zines, the newspapers of eras gone by, the films, the music, and the tapes, in and outside national, provincial, and local libraries fuels what a better world could be. What it must start with, however, is reimagining the archive and its exclusive practices informally and otherwise.