Chronic pain is not unique to adults; it affects millions of children and teenagers worldwide. In fact, about one in four children will experience a period of chronic pain—pain which lasts three months or more—at least once in their lives. This often-invisible burden can interfere with school, friendships, physical activity, and emotional well-being, significantly impacting quality of life.

When improperly treated, chronic pain affects more than just the child. It can ripple through families, causing stress, disrupting daily routines, and leading to financial hardship. Over time, poorly treated pain can also increase the risk of chronic health issues and may even shorten life expectancy.

However, there is growing hope for chronic pain treatment through Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE): A method designed to help people understand what pain really is, why it happens, and how the brain and body interact when experiencing it. While PNE and its applications have been well documented in adults, much less is known about its effectiveness in younger populations. At the forefront of this emerging area, researchers at McGill University are now spearheading efforts to explore how to adapt PNE to help children and adolescents living with chronic pain.

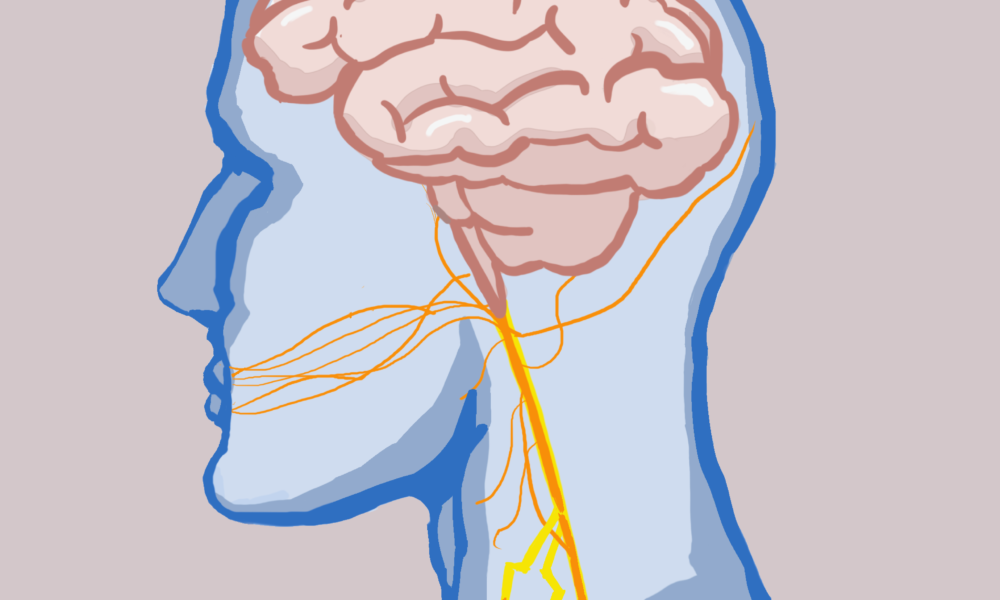

“Key strategies of PNE include the use of simple explanations, metaphors, images, interactive games, videos, and stories to teach concepts like how the brain processes pain, the role of emotions and thoughts, and how active coping strategies can help manage pain,” Felipe Reis, adjunct professor at McGill’s School of Physical and Occupational Therapy, explained in a written statement to The Tribune.

Noticing the lack of research on PNE for children and teens, Reis designed a study to explore how this promising educational approach is being used in pediatric settings.

“Our study addresses the lack of information about how PNE is delivered to children and adolescents,” Reis shared. “While PNE is well-studied in adults with chronic pain, there was very limited knowledge about what topics are covered, how the education is adapted for younger audiences, and how it is delivered in pediatric populations.”

The findings revealed wide variation in how PNE is designed and delivered to younger patients. Most programs addressed essential topics including psychological and social factors, pain-related concepts, coping mechanisms, and neurophysiology—how pain works in the body.

Some also included more advanced ideas, such as how pain shifts from acute to chronic and the brain’s ability to adapt through neuroplasticity.

When it came to the delivery of PNE, Reis found that programs used a wide range of methods.

“PNE was delivered through slideshows, educational videos, booklets, board games, comic books, virtual reality, and even mobile applications,” Reis wrote. “These strategies often aimed to make complex concepts more engaging and understandable for younger audiences by using visuals, storytelling, and interactive formats.”

The length and number of sessions also differed from adult programs. In children, PNE was usually delivered in one to six sessions, each lasting between 8 and 60 minutes—shorter and more concise than typical adult sessions. These adjustments can better align with children’s developmental stages and attention spans.

“The diversity in content, formats, and dosage reflects the early stage of research in this area and highlights the need for more standardized and developmentally sensitive approaches when implementing PNE for children and adolescents,” Reis noted.

His study is the first to map out exactly how PNE is being used with younger populations, providing an important foundation for future research and clinical work.

Looking ahead, Reis recommends that future studies focus on outcomes that matter most to young patients and their families, such as pain levels, physical activity, sleep quality, emotional health, stress, and family dynamics.

“Based on our findings, future studies should prioritize the development of age-specific PNE interventions that are carefully tailored to children’s cognitive and emotional development,” Reis wrote. “More research is needed to determine the optimal “dosage”; that is, the ideal number and duration of sessions to maximize learning and behavioral change in children and adolescents.”

His team also suggests that clinical trials explore how PNE works on its own as well as alongside other treatments like exercise. These studies will be key to understanding just how effective PNE can be in helping young people manage pain and lead healthier, more empowered lives.