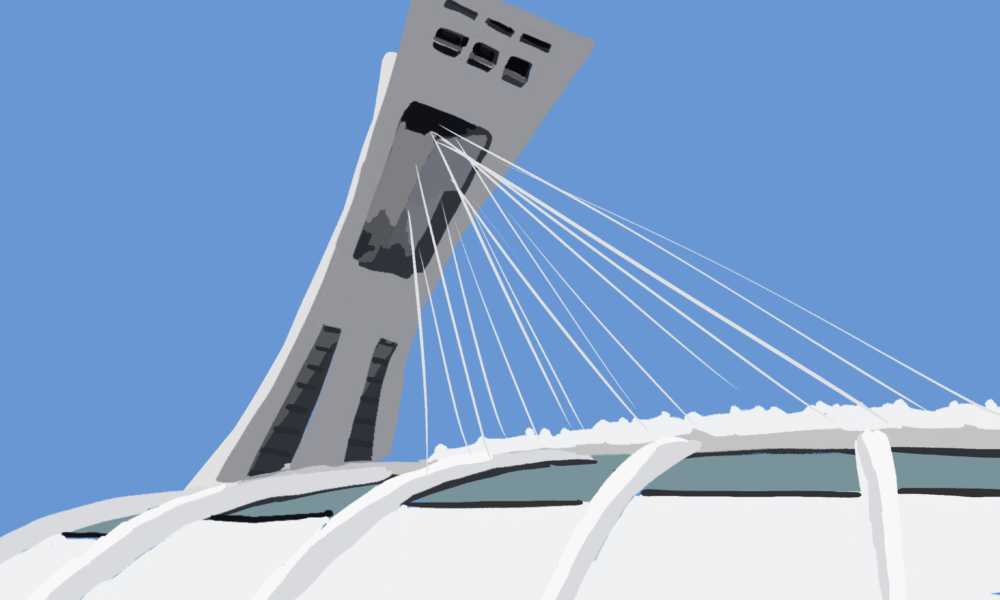

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. To this day, the Olympic Stadium, also known as the Big O, remains one of Montreal’s biggest architectural and cultural landmarks. Featuring the world’s tallest deliberately leaning tower and over 50,000 seats, the stadium is impractical to maintain from an engineering perspective. Due to its hefty maintenance costs, Quebecers frustrated by the continued use of their tax dollars have dubbed the stadium the “Big Owe,” as the facility remains unequipped to host large events, including the upcoming FIFA World Cup.

Despite calls for demolition, Quebec committed long-term to renovating the Olympic stadium. If taxpayers are funding this renovation, the stadium must stop functioning as a historical monument and instead operate as an active, publicly accessible venue that generates global attention through its events, creates quality jobs, and yields measurable economic returns for Montrealers.

The impacts of large government investments in sports stadiums have long been studied to determine the extent of their benefits to the surrounding communities. Academics largely agree that publicly funded stadiums rarely deliver strong measurable economic returns, often mostly profiting the few wealthy team owners and executives. Large stadiums rarely generate meaningful economic output such as higher local property values, tax revenue, or employment. The Big O’s inability to regularly host large events since the Expo’s 2004 departure shows that these indicators are even lower compared to other cities with fully functioning stadiums of similar capacities. These findings rightfully fuel public skepticism toward continued spending on the Olympic Stadium.

Recently, the Quebec tourist minister unveiled an $870 million CAD plan to rebuild the stadium’s roof, which was damaged in over 20,000 areas in 2024. This significant expense is compounded by other costs, such as $28.6 million CAD for the electric system and $20 million CAD for sound equipment. The new roof is anticipated to last only 50 years after the project is finished in 2028.

The other option for the stadium’s fate—demolition—also carries a hefty $2 billion CAD price tag, meaning the stadium will remain whether Quebecers like it or not. So if public money is what’s keeping the stadium alive, the public must be able to access it. To ensure that the investments made in the stadium’s recovery have the best chance at providing economic benefits to all Quebecers, this plan cannot repeat the unwise choices of other cities with large stadiums that have not delivered such benefits.

Meaningful efforts must move beyond renovation and include enforceable commitments regarding how the stadium is used. Investments should guarantee that the stadium hosts and supports community events, youth sports, and cultural programming for Montrealers. If these commitments are made properly with insight and collaboration from local residents, the surrounding neighbourhoods, the city, and the province as a whole would see tangible returns. The Olympic Stadium should function as a shared civic space, not a sealed monument maintained for hypothetical use in the ever-distant future.

Quebec’s hesitancy to develop an investment plan until 2024 led to countless missed opportunities for Montreal to host global events. Perhaps one of the biggest losses was the 2026 FIFA World Cup, where Montreal declined hosting due to financial concerns. Montreal was also unequipped to host Taylor Swift’s record-breaking Eras Tour, which would have brought millions into the city’s economy as it did in other Canadian cities such as Toronto and Vancouver. Missing out on these events caused Montreal to forgo tourism spending, employment opportunities, and international visibility that could have directly supported the city’s small businesses and surrounding communities.

Cities are not recognized globally for simply maintaining their world-famous infrastructure, but for using it to bring people together. Since the Olympic Stadium is here to stay, Quebec has the opportunity to have Montreal recognized on the world stage and make meaningful contributions to its local economies. The public funding for this project should be tied to protocols, including event-hosting benchmarks, community access guarantees, and transparency about its use and impacts. The true cost of the Olympic Stadium is not how much Quebec spends on it, but whether that spending is managed in a way that allows all Quebecers to reap its benefits.