Biographical movies are not a recent phenomenon. From Lawrence of Arabia to Malcolm X, biopics in modern cinema have consistently met commercial success, as audiences seem to have an interest in seeing the lives of famous figures dramatized. But there is always the risk of biopics misrepresenting the lives of those who have passed. How then does one navigate the tension between telling a compelling story and maintaining historical accuracy? Ultimately, script writers can afford themselves creative freedom in crafting an entertaining story, but should still uphold a standard of realism and accuracy.

Take, for instance, Amadeus, a film about the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his rivalry with the composer Antonio Salieri. The costumes in the movie are grand and colourful, the set pieces magical; the movie gives an enchanting, lighthearted depiction of the Age of Enlightenment in Europe. There is, however, a major inaccuracy here: The historical rivalry between Mozart and Salieri was not as sensationalized as the movie portrays—in fact, it was likely based on a rumour. But would audiences want to see a more tame depiction of Mozart? Probably not. Despite the movie’s major historical inaccuracies, it is frequently listed as one of the best biopics of all time.

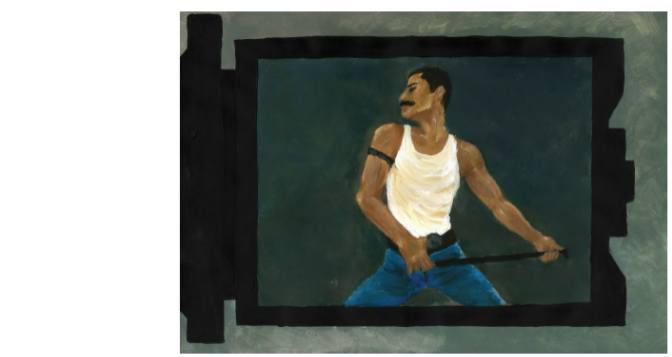

This trend of prioritizing theatricality over accuracy continues in biopic production today. Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman—recent biopics covering the careers of Freddie Mercury and Elton John, respectively—take major creative liberties in depicting real-life events. For instance, Rocketman portrays Elton John’s father as neglectful and unloving, but this fact is heavily contested by John’s own half-brother. In a different, but no less problematic turn, Bohemian Rhapsody diverges from reality by downplaying Mercury’s bisexuality and making it seem as if the band broke up in the early 1980s before their show at Live Aid, which is not the case. In both instances, historical accuracy is diminished in favour of crafting a story for the audience’s enjoyment.

But are there times when theatricality can come before accuracy? With Bohemian Rhapsody, former band members have stated that they liked how the movie turned out, including guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. But who is to say that Freddie Mercury would have approved of the movie—and its portrayal of his sexuality—if he were alive today? Closeting the main character is rather unethical, so situations like this need to be taken into account when writing the script.

These ethical decisions are rarely easy to make. Recall the success of Amadeus, which received critical praise and won numerous awards despite its historical inaccuracy. Mozart did not give his consent to create the movie, and producers today continue to fail to obtain the consent of the figures in question, as seen with the controversy concerning Pamela Anderson’s recent biopic series. Conversely, another celebrated biopic, Steve Jobs, received criticism for inaccurately portraying its titular character by highlighting the negative aspects of his life to make him appear as less loving than some people said he was. Both films’ creative liberties provide theatricality that audiences tend to like. But, in this case, some viewers actually did care about the biopic’s rightful portrayal, hinting at the possibility that perhaps the time between a person’s death and the creation of the movie changes viewers’ opinions on the importance of a movie’s historical accuracy. Historical fallacies in biopics are applied rather arbitrarily, so an objective moral solution to the dilemma of “fact or fiction” in cinema is muddled.

However, moral arbitrariness is not always a bad thing. Unless egregiously inaccurate, film creators should allow themselves creative liberties as they see fit. The inaccuracies of Bohemian Rhapsody crosses this paradigmatic line, as closeting the main character fundamentally changes who is portrayed on screen—here, fact should be preferred over fiction. On the other hand, the less serious and more playful inaccuracies of Amadeus are a classic example of when it is acceptable for fiction to rule over fact.

Audiences should be able to enjoy cinema, but some degree of historical reality should also be preserved. Although these two tend to be at odds in an industry specifically made to be sensational, entertainment value seems to take precedence—sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse.

Biographical movies are not a recent phenomenon. From Lawrence of Arabia to Malcolm X, biopics in modern cinema have consistently met commercial success, as audiences seem to have an interest in seeing the lives of famous figures dramatized. But there is always the risk of biopics misrepresenting the lives of those who have passed. How then does one make sure that deceased figures would approve of how they are represented on screen? Ultimately, script writers can afford themselves creative liberty in crafting an entertaining story, but should still uphold a standard of realism and accuracy.

Take, for instance, Amadeus, a film about the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his rivalry with the composer Antonio Salieri. The costumes in the movie are grand and colourful, the set pieces magical; the movie gives an enchanting, lighthearted depiction of the Age of Enlightenment in Europe. There is, however, a major inaccuracy here: The historical rivalry between Mozart and Salieri was not as sensationalized as the movie portrays—in fact, it was likely based on a rumour. But would audiences want to see a more tame depiction of Mozart? Probably not. Despite the movie’s major historical inaccuracies, it is frequently listed as one of the best biopics of all time.

This trend of prioritizing theatricality over accuracy continues in biopic production today. Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketman—recent biopics covering the careers of Freddie Mercury and Elton John, respectively—take major creative liberties in depicting real-life events. For instance, Rocketman portrays Elton John’s father as neglectful and unloving, but this fact is heavily contested by John’s own half-brother. In a different, but no less problematic turn, Bohemian Rhapsody diverges from reality by downplaying Mercury’s bisexuality and making it seem as if the band broke up in the early 1980s before their show at Live Aid, which is not the case. In both instances, historical accuracy is diminished in favour of crafting a story for the audience’s enjoyment.

But are there times when theatricality can come before accuracy? With Bohemian Rhapsody, former band members have stated that they liked how the movie turned out, including guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. But who is to say that Freddie Mercury would have approved of the movie—and its portrayal of his sexuality—if he were alive today? Closeting the main character is rather unethical, so situations like this need to be taken into account when writing the script.

These ethical decisions are rarely easy to make. Recall the success of Amadeus, which received critical praise and won numerous awards despite its historical inaccuracy. Mozart did not give his consent to create the movie, and producers today continue to fail to obtain the consent of the figures in question, as seen with the controversy concerning Pamela Anderson’s recent biopic series. Conversely, another celebrated biopic, Steve Jobs, received criticism for inaccurately portraying its titular character by highlighting the negative aspects of his life to make him appear as less loving than some people said he was. Both films’ creative liberties provide theatricality that audiences tend to like. But, in this case, some viewers actually did care about the biopic’s rightful portrayal, hinting at the possibility that perhaps the time between a person’s death and the creation of the movie changes viewers’ opinions on the importance of a movie’s historical accuracy. Historical fallacies in biopics are applied fairly arbitrarily, so an objective moral solution to the dilemma of “fact or fiction” in cinema is muddled.

However, moral arbitrariness is not always a bad thing. Unless egregiously inaccurate, film creators should allow themselves creative liberties as they see fit. The inaccuracies of Bohemian Rhapsody crosses this paradigmatic line, as closeting the main character fundamentally changes who is portrayed on screen—here, fact should be preferred over fiction. On the other hand, the less serious and more playful inaccuracies of Amadeus are a classic example of when it is acceptable for fiction to rule over fact.

Audiences should be able to enjoy cinema, but some degree of historical reality should also be preserved. Although these two tend to be at odds in an industry specifically made to be sensational, entertainment value seems to take precedence—sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse.