The Vietnam War and the correlated counterculture movement disenchanted many young people with the way society functioned, and for some, the outlet to this frustration was murder. The ‘60s also saw a rise in serial killers, including Charles Schmid—also known as the Pied Piper of Tucson—who murdered three young women between 1964 and 1965. During that same year—1965—Bob Dylan wrote the song “Its All Over Now, Baby Blue,” supposedly about the end of his relationship with singer Joan Baez. In 1966, Joyce Carol Oates combined Dylan’s song and the story of the Schmid murders and wrote the short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” in which she brings one victim’s experience to life. There is no explicit connection between Dylan’s song and the Schmid murders, but the farewell ballad has strong connections to the murders and to Oates’ story. The story, especially with its connections to the murder and Dylan’s song, is emblematic of the influence of music changing societal norms that led some young men to take drastic and tragic action at the cost of innocent lives.

In “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” Connie, the protagonist, is presented as a typical young teen: Vain, jealous, frustrated with her overbearing mother, and obsessed with the boys she meets at a drive-in restaurant near the highway. In “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” Dylan cautions, “The highway is for gamblers, better use your sense,” in a foreboding nod to the incident that, for Connie, starts at the restaurant by the side of the road. Just a few months before these words were written, Schmid drove at length into the Arizona desert and murdered his first victim, Alleen Rowe.

Connie’s idyllic world is constantly infused with the soundtrack of new rock-and-roll tracks that were hitting the radio stations in the ‘60s. Beside the highway, late at night, it’s the music and comfort of the restaurant that draw together the victim, Connie, and her eventual murderer. There on one Saturday night, Connie catches the eye of a strange-looking man, with “shaggy black hair” that looks off, almost like a wig. He “wagged a finger and laughed and said, ‘Gonna get you, baby.’”

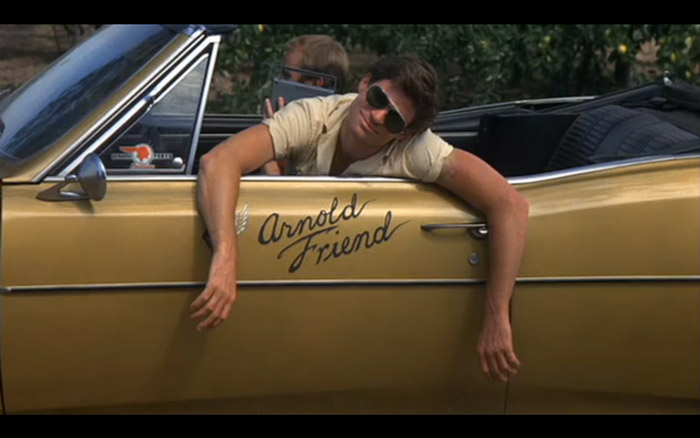

The next day, Connie lounges around the house, parents gone, listening to the radio, her long blonde hair drying in the sun. A car pulls up on the gravel drive and the same man from the previous night emerges. Connie approaches the screen door with caution, allured by the flattery of this man remembering her from the previous night. The man introduces himself as Arnold Friend, and invites her for a drive. In 1966 Dylan wrote, “Strike another match, go start anew / And it’s all over now, Baby Blue.” Dylan’s song reiterates that it’s all over, and there’s nothing more to be done. Arnold speaks to Connie in a similar way, manipulating her into believing that she has no choice but to go with him—both the song and fiction are alike in their genre of defeatism.

Arnold Friend reminds Connie that she has no home anymore; “The place where you came from ain’t there any more, and where you had in mind to go is cancelled out.” This assertion mirrors both the Dylan line “Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you,” and the terrible image of Rowe leaving her home for the last time.

Arnold’s companion, Ellie, sits in the car playing the radio on the same station that Connie had in the home. Although Connie doesn’t let her in, Arnold creates a line of connection between them through the music, which plays simultaneously inside and outside the house. Arnold blurs the line between inside and outside, between safety and danger. The spell of music is also present in the story of the Schmid murders. As he murdered his first victim, Shmid’s girlfriend at the time sat idly in the car, listening to the radio.

The fact that music is so present in Oates’ story, and also is a small detail in the Schmid murder, is reflective of the fact that music was beginning its transition to the forefront of popular culture; becoming the powerful force that it did during the ‘60s. At that time the music industry was changing rapidly, and some older generations claimed that the new rock ‘n’ roll style was depraved and frivolous. A murder, a song, and a story came to fruition during this time—a love triangle of tragic inspiration.