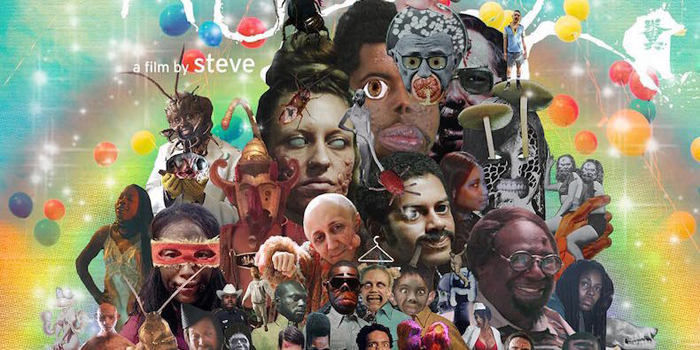

The magic of cinema lies in projected images’ power to profoundly move us. Everybody knows what it feels like to laugh at Ghostbusters (1984), or to cry at Marley & Me (2008). Kuso, the new film directed by the electronic musician Flying Lotus, demonstrates the power of movies to move us in a different way: That is, to gross us the fuck out.

Kuso prompted walkouts when it premiered at Sundance, along with awed reviews declaring it the “grossest movie ever made.” Even before it screened as part of FilmPOP (the film component of Pop Montreal), a Cinema du Parc employee gave a blunt warning: “This movie is really fucked up.”

Kuso is spectacularly, mercilessly disgusting—a film difficult to describe and even harder to watch. It is a journey into the darkest depths of the human subconscious. Unfortunately, in spite of the countless bodily substances smeared across the screen, the film itself lacks substance. Kuso engages neither the mind, nor the heart, but rather the gag reflex.

Imagine an experimental conceptual short made by a hipster film student, then cross it with The Human Centipede (2009). This is Kuso. The plot, as far as can be ascertained, follows the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in Los Angeles—weaving together the stories of several survivors. In one scene, a boy befriends an alien creature in the woods—and then feeds it his excrement. At another point, a talking cockroach appears out of nowhere and declares, “Do not fear the feces.” It’s not a joke, but rather a necessary piece of advice, for it’s hard to overstate the sheer quantity of feces—along with pus, blood, and semen—in which the film is drenched throughout its 92 long minutes.

Alternating between jarringly indiscernible plot lines and confusing visual tangents, Kuso is a disorienting experience, creative if not cohesive. One highlight is the soundtrack, an ominous groove created by Flying Lotus himself, along with various artists including Aphex Twin and Thundercat. The music gives the film an underlying consistency, which it otherwise lacks.

Occasional relief comes from the film’s perverse humor, and the best moments of Kuso are its funniest as well. When you laugh at a woman getting hit in the face with her own fetus, you’re also laughing at how quickly your own morals have degraded.

At times Kuso hints at aspirations of becoming something more than a gross-out flick, like in the segment of spoken word poetry referencing “21st-century power structures.” Yet the film teases such themes only to fall back into self-indulgent depravity. That’s a shame, because a post-quake Los Angeles would be a perfect setting for an allegorical look at American society, and the shock of Kuso would have been more powerful if there was something thought-provoking underlying it.

Instead, the film is primarily an experiment in just how far the moviegoer is willing to be pushed. “When will you walk out?” it seems to ask. When a cockroach emerges from the therapist’s anus? When a guy gets a blowjob from the talking boil on his girlfriend’s neck? Kuso makes you question your own limits, even if you don’t want to.

Kuso is a difficult experience to communicate. Just as the film’s earthquake bonds its survivors together, the film itself creates a special bond between anyone who sits through it. For better or for worse, it’s hard to forget.