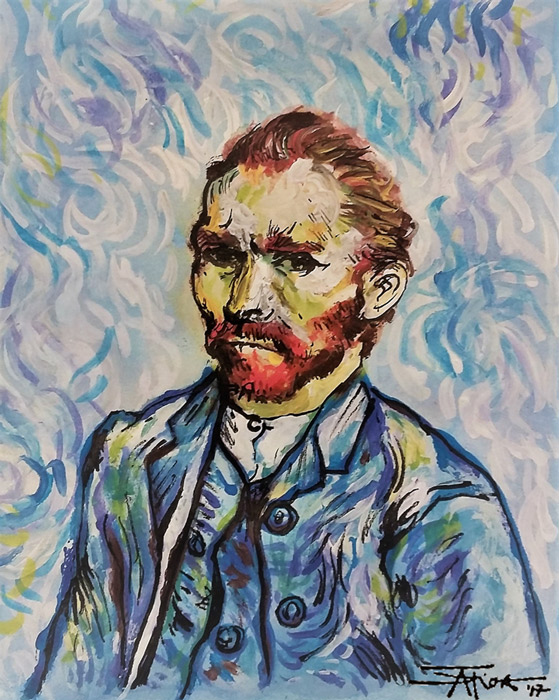

Loving Vincent, to put it simply, is a work of art. Directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, the film advertises itself as “the world’s first fully painted feature film.” Each shot in the film was hand-painted in Vincent Van Gogh’s style by a team of over 100 artists. A Polish-British co-production with a budget of US $5.5 million, $70,000 of which were raised in a Kickstarter campaign, the film succeeds as being the first of its kind, engaging viewers in its immersive, dramatic story.

The events of the film take place one year after Van Gogh’s (Robert Gulaczyk) death. The postman (Chris O’Dowd) who collected Van Gogh’s many letters, requests that his son Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth) personally deliver Van Gogh’s last letter, written to his brother, Theo. On this journey, Roulin meets people who interacted with Van Gogh in different ways. Listening to all of them speculate on the cause of Van Gogh’s alleged suicide, Roulin must distinguish fact from fiction in order to get to the truth.

The hand-painted nature of each still creates a distinct visual dynamism. The film finds its appeal not in a speedy plot, but in sequencing its 65, 000 meticulously painted stills. From European cafes to scenic backyards and starry nights, the film’s scenery wonderfully replicates Van Gogh’s aesthetic. The animation never comes across as abrupt or unpolished—even shots of clouds and cigarette smoke feel fluid and realistic. The project is ambitious, depicting a range of technical scenes, including distorted point-of-view shots, nightmares, and dramatic flashbacks.

Loving Vincent is reflective but also, surprisingly, investigative. Roulin’s attempts to uncover the truth by retracing Van Gogh’s steps could be straight out of an Arthur Conan Doyle mystery novel. The film’s score (composed by Clint Mansell) employs string instruments and choir vocals to produce a mystical, curious mood. The balance between dialogue and music is highly effective; while the film does rely heavily on dialogue to develop its characters, the dialogue recedes in the more emotionally-charged scenes, which fittingly swell with cinematic music.

The actors’ voice work breathes life into the characters. Jerome Flynn’s stiff voicing communicates the sophisticated—at times arrogant—personality of Paul Gachet, Vincent’s friend and psychologist. Eleanor Tomlinson’s performance as Adeline Ravoux, the caretaker of the inn in which Vincent dies, is lively and charming.

The film develops an immersive narrative with a limited host of characters, but in doing so cannot create a complex plot. The movement from one scene to the next, especially in the first half, is predictable and repetitive. Over the course of his journey to deliver Vincent’s letter, Roulin gets constantly redirected to different locations. The screenplay does not make this inconspicuous, perhaps for the worse; the turns in plot are very explicit, at times even on-the-nose. Nevertheless, this conventional structuring becomes less visible in the latter half, in which the suspense of the story culminates.

Loving Vincent successfully depicts Van Gogh as a likeable character, without romanticizing his mental state. The film praises Van Gogh’s eccentric creativity, while also capturing the mistreatment he faced at the hands of those who saw him as a “nuthead.”

Ultimately, Loving Vincent’s storytelling is simplistic but charming, prioritizing characterization over development. With dynamic visuals and a palpable mood, Loving Vincent is a visually stunning and moving depiction of the complexity of human emotions and the difficulty of processing the death of a loved one.