When thinking of museum walls, one does not typically imagine blown-up photographs of leather-clad men engaging in sexual acts. In museums, penises are meant to be covered with little stone leafs, or left flaccid. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ current temporary exhibit Focus: Perfection is the late Robert Mapplethorpe’s largest to date. The exhibit plays with viewers’ expectations and presents sexually explicit scenes as high art. What one would typically keep a secret is thrust into the public eye; however, the atmosphere is anything but awkward.

Mapplethorpe is famous for his controversial images, probing portraits, and self-professed goal of capturing perfection in photographic form. Monochromatic portraits of the New York art scene’s brightest members, such as Patti Smith and Yoko Ono, line the walls of the largest exhibition room. These walls are accented with shades of purple—the colour of royalty, an intentional choice given Mapplethorpe’s tendency to seek aristocratic company. Faint sounds of punk rock music play from speakers, and the exhibit features a large display of art relating to Mapplethorpe’s artistic relationship with Smith.

In the next room, the mood is pensive and mysterious. The dampened music and dim lighting in the portrait hall is interrupted by a caution sign. Visitors are warned by signs at the entrance that if they venture through the rooms on either side of the hallway, they will see sexually explicit content. If they do not wish to see such content, they can remain in the centre hall to look at still life photographs of flowers, the first component of Mapplethorpe’s X, Y, Z series—a later project in which he revisits his favourite subjects.

However, if visitors look at the spaces between these floral photographs, they will catch a glimpse of the extremely sexual scenes that are being showcased in the rooms beyond. The display is fully revealed when one enters the side rooms, where the second component of the series is displayed: A sequence of photographs of gay couples engaging in sadomasochism. Rather than marveling at the pornographic imagery on display, viewers appreciate how beautifully it is presented. Mapplethorpe’s photographs, presented in black and white, are smooth and flawlessly lit. His technique alone demarcates him as a master of his craft.

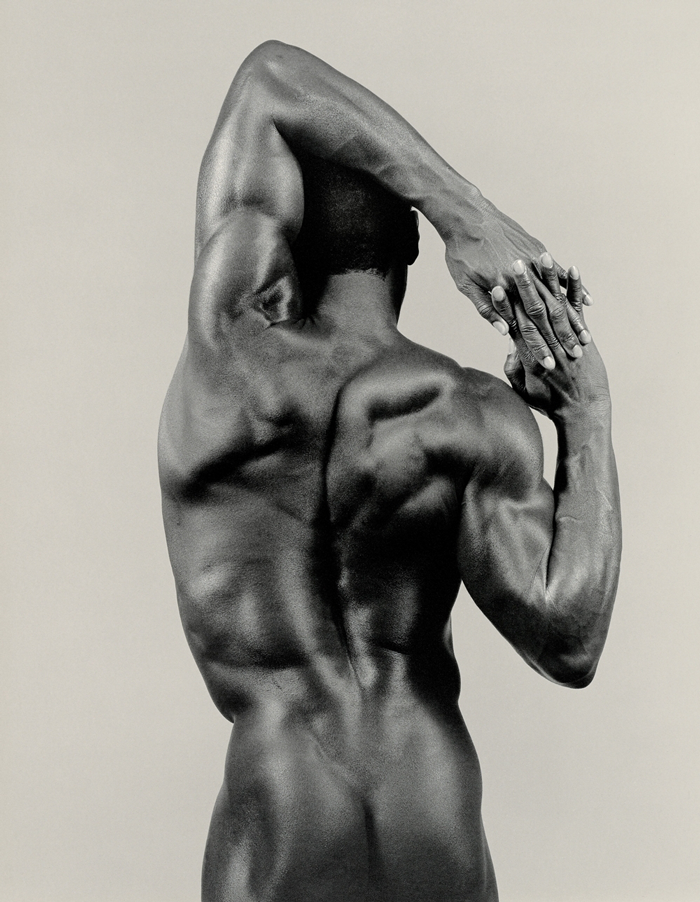

The classical music playing in the background of the next room seems jarring when considering the salacious display in the previous area. Pictures of black men in contorted positions are shown next to images of marble statues. These statues challenge high art’s longstanding tradition of sculpting bodies out of white marble—a trend which implicates that whiteness is a hallmark of high art. This comparison has been criticized as fetizhising, but it is important to note that Mapplethorpe treats the bodies of most of his subjects as sculptural objects. In his non-portrait works, personal identity takes a backseat to aesthetic perfection. Mapplethorpe’s technique certainly succeeds in pleasing the eye.

The final space of the exhibit focuses on the reception of Mapplethorpe’s work, which was exhibited at a crucial time during the American Culture Wars of the 1980s and 90s. Many groups protested the presentation of his work in museums due to its so-called scandalous nature, and claimed his work was not art.

In interviews from the 1980s, shown on the wall alongside the critiques, many interviewees compliment his formal technique and treatment of sensitive subjects. Each of Mapplethorpe’s photographs reveal the hand of a perfectionist and a confident master. As the interviewees claim, his work should be treated accordingly. Although the critical comments are valid, they seem to intentionally avoid talking about the taboo subjects that the photographs overtly address. Focusing on formal attributes over subject matter plays into Mapplethorpe’s artistic intentions: The viewer is not meant to focus on the subject, but on the beautiful way the subject is presented.

Some viewers believed Mapplethorpe was glorifying porn, presenting salacious photographs as art in order to gain notoriety. These critics, however, must have never seen his art in person. Mapplethorpe’s sincerity is apparent through the awe-inspiring mastery of his technique. One would be hard pressed to find another room in the world where it feels comfortable to view explicit sexual scenes while standing next to strangers.

This exhibit runs at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until Jan. 22. Admission is $12 for those under 30, $20 for ages 30 and up. Learn more at mbam.qc.ca.