Canada’s social economy is replete with innovators inspired by a global consciousness that transforms oppression into opportunity. It is a sector that is neither publicly nor privately controlled and touts one of the fastest growth rates in the country.

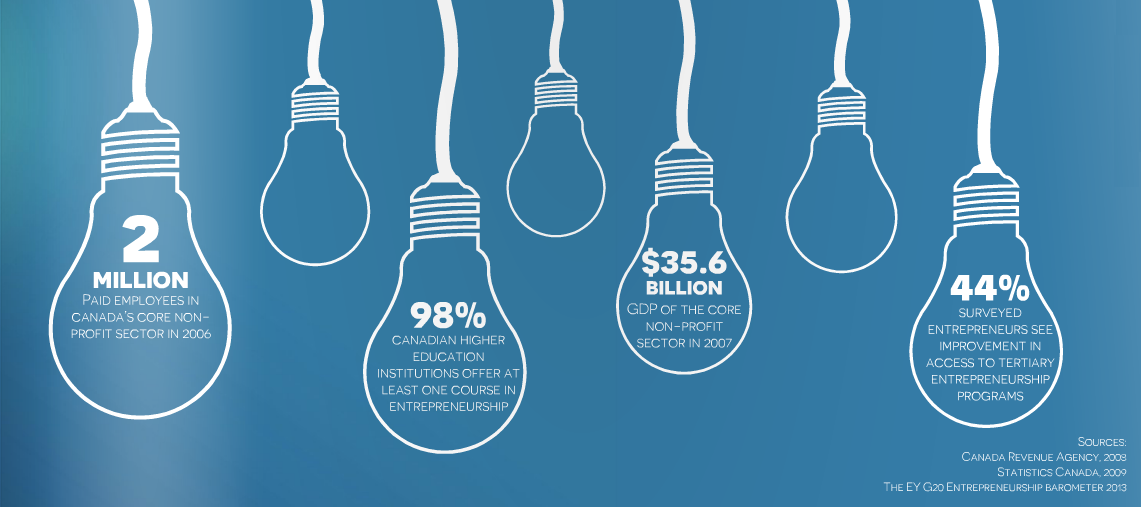

According to Statistics Canada, non-profit industries contributed $35.6 billion to the national economy in 2007, exceeding the value added by the agricultural industry more than two-fold and that of the motor vehicle manufacturing industry several times over. Within the social economy, entrepreneurs are leveraging the market system to think critically for solutions to the world’s most pressing economic, environmental, and social problems. Through critical interdisciplinary learning, niche mentorship, and networking opportunities, academic institutions like McGill are positioned to foster the talents of young innovators who inaugurate and add value to organizations within one of the fastest-growing sectors of the Canadian economy.

And much like a university cannot be represented by one feature, its methods for encouraging students to engage in the social economy can be seen at multiple levels of the institution.

Emulating empathy: a pedagogy of interdisciplinarity

Industry Canada reported that 98 per cent of higher education institutions in the country offer at least one course in entrepreneurship; however, entrepreneurs surveyed by the 2013 Ernst & Young (EY) G20 Entrepreneurship Barometer were critical of Canada’s lack of coordinated support for entrepreneurship and weak mentorship opportunities. In 2012, the Desautels Faculty of Management began to institutionalize a pedagogy tailored to address this issue by launching MGPO 438, an undergraduate elective called “Introduction to Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation.”

Anita Nowak, former integrating director of the faculty’s Social Economy Initiative (SEI) and professor of MGPO 438, noted how social entrepreneurship can invigorate new forms of academic instruction.

“It is a catalyst for different ways of teaching across the entire university system,” Nowak said. “Social innovation is about systems change. Any specific problem in one area has its tentacles in other issues, and systems-thinking addresses this holistically.”

Mentorship and outreach occupy a central place in the curriculum of Nowak’s popular course. The class features guest-speakers who serve as role models in the social economy.

The momentum of what Nowak coins the “social entrepreneurship zeitgeist” is establishing its foothold in the Faculty of Management, as the SEI plans to scale its efforts to offer related courses relevant to the social economy.

However, Nowak still sees room for improvement.

“There should be more opportunities that intentionally foster cross-border interdisciplinarity between management and other faculties,” Nowak said, emphasizing the ability of universities to magnetize and bring together the world’s brightest minds. “Every faculty on campus can contribute to social innovation. The convergence of different ways of problem-solving situates social entrepreneurship now in a great moment in time.”

Universities are often able to instigate important and informed conversations about specific social problems that can benefit from interdisciplinary dialogue and experiential learning. U3 International Management student Joanna Klimczak and McGill alumnus Mariana Botero worked tirelessly to pioneer the new Social Business and Social Enterprise Concentration within the faculty. They were both conscious of the advantage of interdisciplinary studies in the context of social innovation. This option allows Management students to integrate classes that focus on corporate social responsibility and social impact with those offered under the International Development Studies curriculum, in addition to other related courses outside the Faculty of Management.

As McGill moves forward, Klimczak hopes the new concentration will serve as fuel to energize a new generation of business leaders.

“It’s one thing to create an idea, and another to make it happen in a large institution with resource limits,” said Klimczak. “While certain management courses definitely [impart] skills for social entrepreneurship, this concentration will be a lot more encompassing.”

The university will thus be urged by students to temper its desire for innovation with the constraints of its structure as an administration.

“McGill is taking a step in the right direction, but its bureaucracy as an institution stifles innovation,” said Sean Reginio, U3 Arts, who completed Nowak’s course last Fall. “Procedures as simple as room-booking for meetings and venues on campus are difficult in an institution of McGill’s size.”

U3 Management student Nikita Pillai echoed this sentiment.

“McGill is a mecca for talent and skill,” Pillai said. “But, for as long as bureaucratic red tape exists, there will be inertia in academic innovation.”

Fostering confidence and competition

Through competitions and mentorship opportunities, universities can become micro-environments with the potential to address gaps in the public sector’s existing services supporting young entrepreneurs. According to Industry Canada, these shortcomings include unreliable access to start-up funds, long-term mentoring, and restrictions on a young entrepreneur’s eligibility for government assistance. HackMcGill and Computer Science Undergraduate Society’s (CSUS) McHacks—a 24-hour inter-university undergraduate hackathon—and the McGill Dobson Cup, a start-up competition, provide world-class mentorship opportunities from industry professionals and encourage inter-disciplinary solution-making.

“The Dobson cup could be the natural springboard for social enterprises to launch by gaining exposure to key impact investors,” Nowak said. “If [students] don’t have interface opportunities, innovation may never happen.”

Rewarding ingenuity through mentorship and thousands of dollars can make the formative difference in helping a young entrepreneur overcome significant barriers when starting a venture.

“I always knew that I had an interest in entrepreneurship, but it’s risky,” said U3 Arts Jessica Wang—who won first prize at the Dobson Cup in its social enterprise track. She and with her partner Jassi Pannu co-founded Sanitru, a social enterprise dedicated to reducing the incidence of drug treatment errors. “The social and financial support network gave me the confidence to pursue entrepreneurship. If we hadn’t won the Dobson, I don’t know if I would have tried.”

More so than through pedagogy, the university steps up to its role as a true catalyst for social innovation by galvanizing networking opportunities outside of the classroom.

McGill regularly mobilizes its resources to sponsor summits and symposiums that give students exclusive opportunities to interface with high-profile leaders and social entrepreneurs at little to no cost. Within the past academic year alone, McGill welcomed Thomas Mulcair, Justin Trudeau, former vice-president of the United States Al Gore, and Elizabeth May. Mentorship often inspires a certain veneer of confidence in young innovators to consider a vocation in social entrepreneurship.

“I didn’t plan for [Nobel Peace Prize winner] Muhammad Yunus to come to Montreal […but] I approached him at a global leadership summit at McGill about [starting] an incubator and accelerator for young people,” said Klimczak, who is also the President and Co-founder of myVision, a student-run business that focuses on creating social business projects. “He told me to envision the world and how you live in it. Then you can create that world. That’s how myVision was born.”

The myVision initiative leverages education as the fulcrum to resolve local challenges within Montreal, providing university and high school students with an understanding of how social business projects can sustain palpable community-level change.

“Social business was a way for me to personally integrate my life, career, and care for community,” Klimczak said.

Opportunity within the campus network

A major advantage of a campus environment is the wide array of clubs and organizations as well as internships offered to university students.

Internship programs facilitated through individual faculties at McGill also foster a social ecology that makes academic development come alive through praxis. New to Desautels is the SEI impact internship program which partners students with Montreal-based non-profit organizations engaged in social finance and fostering social innovation such as the Jeanne Sauvé Foundation and Artistri Sud.

“The network I have moving forward is way bigger than it ever would have been if I had never [attended] university,” admitted Reginio, who completed an SEI impact internship during its pilot year in 2013. “The intuition you gain about how to lead and manage the human dynamics of a team is from practice with real experience—everything [outside] the classroom. Through niche opportunities and experiences [facilitated by] McGill, I became comfortable with the idea of entrepreneurship as a potential career.”

The number of possibilities for student engagement in McGill’s hundreds of clubs and services has the potential to impart crucial skills that can add significant value for would-be entrepreneurs.

“A general skill-set derives from an executive position […] in extracurricular leadership,” said Pillai, who is also the former vice president external of McGill Women in Leadership. “Student organizations tend to have specific mandates, and students learn to tailor their communications and sell their ideas in accordance with that mandate.”

McGill’s robust approach to social innovation is supported by a campus-wide ethos supporting of community engagement. This operates on several scales through outward-oriented initiatives such as the Social Equity and Diversity Education (SEDE) office’s Community Engagement day and faculty-level working groups such as the Arts Community Engagement Committee. The university is able to further encourage critical thinking about social initiatives through inward-oriented social financing opportunities such as the McGill Sustainability Projects Fund and through the dozens of charitable organizations, leadership accelerators, and social activism groups that are financed by the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU).

The university-wide commitment to community engagement also helps to form networks that indirectly nurture the seedlings of students’ visions of social change into concrete projects.

Saba Balvardi, U2 Science, arrived at McGill from a small village in Iran with an initiative to address the pediatric health concerns of underserved communities in the southern province of her country, but lacked the network to do so. Meeting likeminded students with similar interests and complementary skillsets through the Muslim Students’ Association enabled Balvardi to start Project Hiva, a student-run initiative that translates and produces culturally-sensitive illustrations for Canadian Paediatric Society health education brochures issued initially in English.

“Joining different groups at McGill helped make Project Hiva possible,” Balvardi said.

The confluence of McGill’s resources provide long-term opportunities for students with visions that look beyond business and more towards a more equitable social economy.

Prospects for progress

Within McGill, innovators can look forward to myVision McGill’s social business summit on March 28, anticipated as the largest of its kind to ever take place at the university. The summit invites social entrepreneurs to facilitate social business workshops, culminating in the launch of the myVision internship database and a virtual address delivered from Yunus himself.

Social innovation is not just the flavour of the month, but the refrain of our generation. As the social economy becomes an increasingly attractive entry-point into the workforce, Nowak advised that students not ask, but demand that courses and observable institutionalized support for social innovation across all levels of the university be made available and accessible to students.

“What is required is a concerted effort across a critical mass of students,” Nowak said.

She encouraged students to reframe the parameters of their expectations for the future.

“University is the best time of your life [to consider social entrepreneurship] because you are unburdened by major responsibilities,” Nowak said. “When people are in alignment with what they’re meant to be doing, coincidences and doors open up and allow that energy to flourish.”