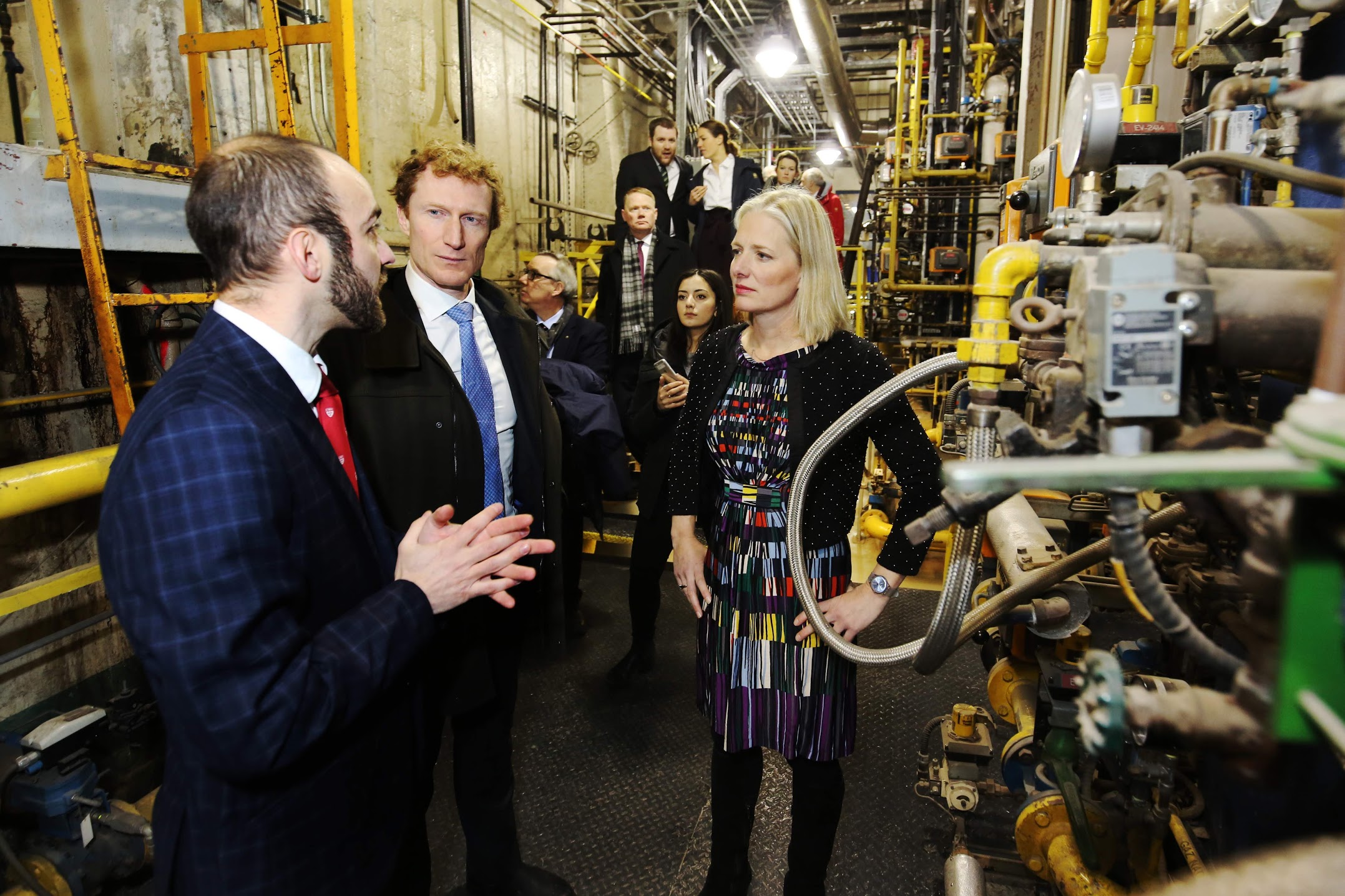

McGill has received $1.8 million in funding from the Canadian federal government’s Low Carbon Economy Fund (LCEF) for three projects aimed at lowering the university’s carbon footprint. Catherine McKenna, Canada’s minister of Environment and Climate Change, visited McGill on Feb. 22 to announce the decision.

“The federal government is partnering with McGill University, where McGill will receive up to $1.8 million under our Low Carbon Economy Challenge,” McKenna said. “We challenge businesses, universities, hospitals, and schools around Canada to come up [with] solutions that will reduce emissions, and McGill came up with a very practical solution.”

According to Interim Director of Utilities and Energy Management Jerome Conraud, McGill’s greenhouse gas emissions totalled 56,004 tonnes in 2017. With the LCEF funding the decarbonization of McGill’s energy systems, that number is expected to be reduced by 18 per cent. The first project, which will take place during summer 2019 at the Gault Nature Reserve, will convert all remaining oil heating boilers on the site to electric ones. Once the conversion is complete, Gault’s only source of greenhouse gas emissions will be its fleet of vehicles.

The second project, set to take place during summer 2020, consists of replacing one of the four natural gas boilers in the downtown campus powerhouse with an electric one. The space freed up through this change will accommodate the third project, the installation of a heat recovery system, during summer 2021.

Conraud explained that carbon dioxide and methane, by-products from burning natural gases, contribute to global warming by trapping heat in the atmosphere. Since electricity in Quebec is not generated by burning natural gases, converting McGill’s energy systems to electric will significantly reduce the institution’s carbon emissions.

“In the United States and Alberta, for instance, the electricity they consume comes mainly from coal or natural gas,” Conraud said. “Instead of using dams, as they do in Quebec and [British Columbia], or instead of using windmills, they burn coal or oil or natural gas, and that generates a lot of carbon dioxide.”

McGill’s high energy consumption is a product of its research capacity. Conraud pointed out that most of the power is dedicated to ventilating the university’s labs.

“What consumes [the] most energy at McGill is research labs,” Conraud said. “We do have a lot of research labs. We have fume hoods, and because we need to constantly evacuate contaminants in the air so that people can work safely in labs, we have high ventilation rates.”

McGill Climate Officer Ali Rivers believes that the LCEF will play a key role in helping McGill realize its Vision 2020 sustainability strategy, particularly its long-term goal of carbon neutrality by 2040.

“We would’ve converted one of those boilers at some point down the line, but it would have been more on the long-term goals,” Rivers said. “This is so great because the sooner we do these conversions, the sooner we are reducing our legacy footprint. Once that electric boiler is installed, 8,600 tons of CO2 will be reduced every year.”

Rivers referred to McGill’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 2017, which includes comparisons between McGill and other Quebec and American universities. McGill’s level of 1.02 tons of carbon dioxide emitted per student in 2017 might appear modest compared to Harvard University’s 9.20 tons per student; however, the University of Montreal proves to be even more carbon friendly with carbon dioxide emitted per student at only 0.59 tons.

“Generally speaking, McGill has a higher relative footprint per student and per square foot than other Quebec universities mainly due to size and research intensity,” Rivers said. “But, we have a lower footprint than all of our American peers, and that is a result of our electricity grid, which is renewable.”

Rivers suggested that McGill staff and students can make choices everyday such as carpooling, taking public transit, and turning off electronics that are not in use to help reduce their personal carbon footprint.