Bike gates, a pedestrian-friendly campus, and a car-free McTavish Street are more than just factors of everyday life at McGill. They are all guided by the university’s Physical Master Plan, a document adopted in 2008 that outlines priorities for the development of McGill’s downtown and Macdonald campuses.

The Physical Master Plan

The plan lists nine core principles, including preserving historical buildings, keeping campus accessible, and upholding the university’s academic mission. With an overarching principle of sustainability, the plan directs infrastructure, transit, and landscaping at McGill.

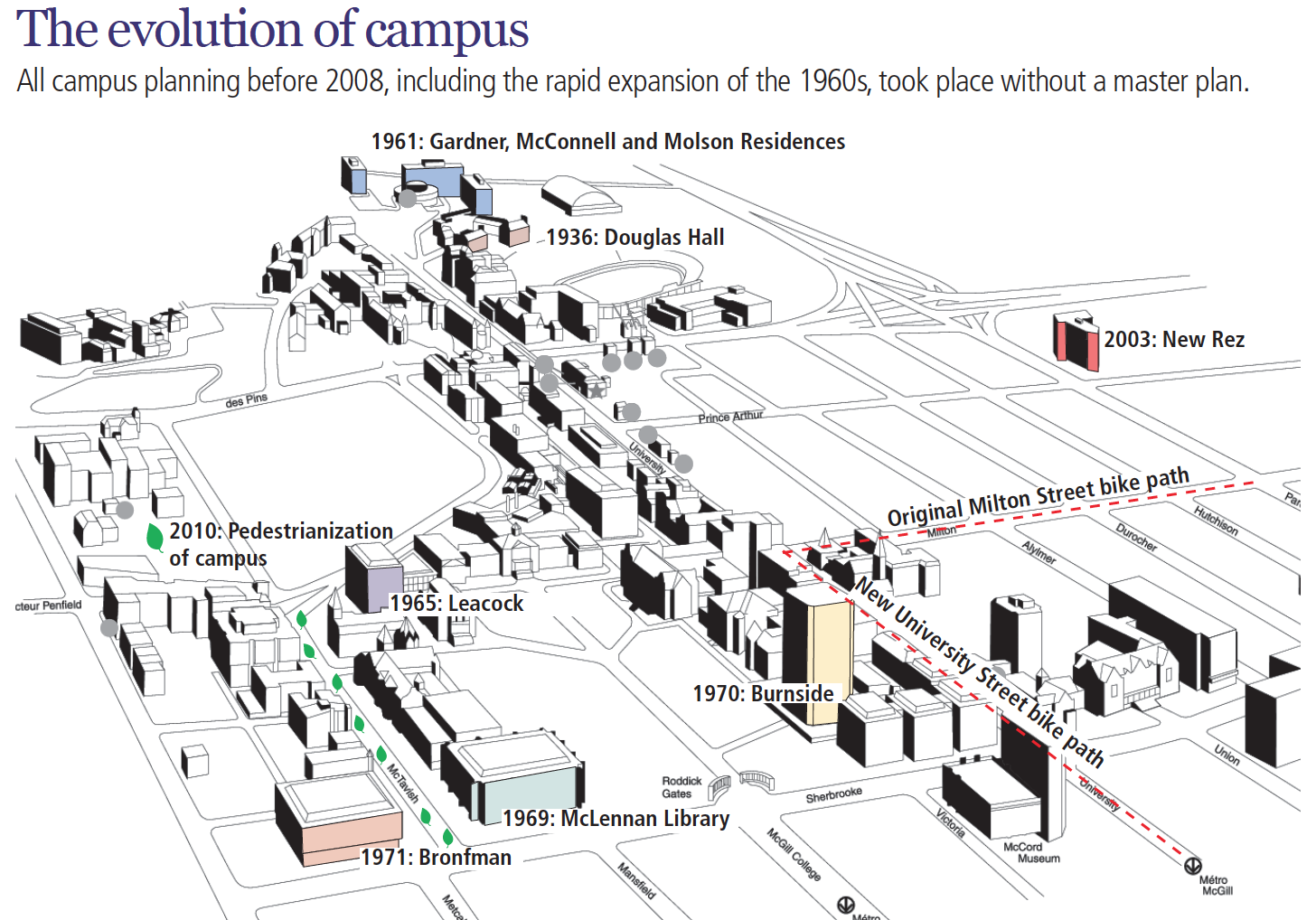

Before the Master Plan was adopted, only disjointed, short-term strategies guided development projects on campus. For example, a large influx of students in the mid-20th century led to the rapid construction of many buildings that fill campus today, including Leacock, Stewart Biology, McLennan Library, and the three upper residences.

“Back in the 1960s, there was huge enrollment growth, so the university was forced to plan major expansion very quickly without a definite vision,” said Chuck Adler, director of Campus and Space Planning (CSP) and a member of the task force behind creating the Master Plan.

To address McGill’s lack of a long-range plan, John Gruzleski, outgoing dean of Engineering at the time, was appointed chair of the task force formed in 2004 to generate a long-term development strategy. Gruzleski began a consultation process to collect input from thousands of people in the McGill and Montreal communities, as well as recommendations from design and planning experts. After two consultation processes over a four-year period, the collected information was distilled into the 75-page document that guides all planning today.

According to Adler, the space constraints of McGill’s downtown location pose specific difficulties. The university must purchase nearby property to expand the campus beyond its current borders, and the real estate market’s unpredictability makes it difficult for McGill’s future development to have a fixed layout.

“Since we have to evolve outside our own territory, we cannot predict where we’re going to be in 10 years,” Adler said. “So the principles [in the Plan] say what’s important to us, and when opportunities come up we can see if they align with those principles.”

Development projects at McGill do not go forward unless they align with the principles of the Master Plan. First, all new projects undergo an evaluation by CSP and University Services. They then receive final approval from various McGill authorities depending on their value—the Board of Governors (BoG) (if value exceeds $5 million), the BoG’s Building and Property Committee (more than $4 million), or senior administration personnel (less than $4 million).

Pedestrianization

When the city of Montreal took an interest in reducing car traffic in the downtown area, McGill seized the chance to pedestrianize campus in accordance with the principles of the Master Plan.

“The university had been talking to the city about this for about 40 years, to make McTavish Street an enlargement of the campus and to make it a better public space,” Adler said. “It wasn’t really planned—it was just an opportunity.”

McGill struck a deal with the city for the university to receive control of McTavish Street in 2010, agreeing to reduce vehicle use on that street and the rest of lower campus. In May 2010, the new pedestrian-friendly campus debuted with restrictions on car and bike use, and deliveries limited to between 7:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m.

“People really wanted to have a greener, more sociable campus where pedestrianization and safety came through as the main priorities,” said Dean of Engineering Jim Nicell, who led the second consultation for the Master Plan. “There was a fair amount of opposition to [the restriction on bike access]. However, there was almost no opposition to the removal of vehicle access from the lower campus.”

However, some students at the time found it difficult to adapt to the restrictions of a pedestrianized campus. Tom Fabian, vice-president internal of the Students’ Society of McGill University (SSMU) in 2010, told the Tribune at the time that the restriction on deliveries brought some challenges.

“[Pedestrianization] has caused tons of hell for us to not have any cars on campus during frosh and Open Air Pub,” he said. “We don’t know when [deliveries are] going to arrive.”

According to Nicell, the pedestrianization of campus was not without its costs.

“It has negatively impacted the university in a financial way, due to lost revenue from parking,” he said. “[But] we accomplished something that will change the face of our university for the next hundreds of years. It will be taken for granted, but it will be incredibly valued.”

The bike gates

Prior to McGill’s pedestrianization of McTavish, the bike path along Milton Street ended at the McGill campus with no connection to the Montreal city centre. This left cyclists with the option of riding against the flow of traffic along University Street for two blocks until they reached the next bike path, or taking a shortcut through the McGill campus.

In 2010, the city built a two-way bike path along University Street to divert cyclists from riding through campus. Since then, McGill has required cyclists to walk their bikes on campus.

Martin Krayer von Krauss, manager of McGill’s Sustainability Office of Campus and Space Planning (CSP), said the rule was created because cycling on campus was deemed “incompatible” with the Master Plan.

“The concern was […] that the safety of pedestrians on campus [and] the speed at which mounted cyclists would travel on campus was incompatible […] with the vision of our campus as a sanctuary within an otherwise hectic urban environment,” he said.

In September 2013, a set of metal swing gates was added to the pedestrian walkway at McGill’s Milton Gates entrance. Associate Vice-Principal (University Services) Robert Couvrette said the bike gates were intended to increase pedestrian safety.

“If cyclists did what the signs asked and dismounted at the entrance, everyone would be very safe,” Couvrette said. “Cyclists who decide to try to ride through the gates or get around them without dismounting are choosing a riskier option.”

The gates, however, received negative attention from some students, including executives from the Arts Undergraduate Society (AUS) and SSMU.

“These gates [make campus] so inaccessible for everyone who isn’t an able-bodied person,” said Joey Shea, SSMU Vice-President University Affairs. “The bike gates sent a bad message to the Milton-Parc community, and more importantly to the Office for Students with Disabilities (OSD).”

Although the administration originally planned to remove the gates this winter to ease snow removal, they were vandalized and taken down prematurely in October. Using the bike gates as a starting point, a working group—including students, faculty members, urban planning experts, and representatives of the OSD and the student-run Flat Bike Collective—is revisiting whether McGill should allow and accommodate cyclists on campus.

Couvrette said more input from the community is necessary before making further moves regarding cycling on campus.

“We are very aware that many people view these gates as a barrier, even though they are not intended to serve that purpose,” Couvrette said. “In evaluating the effectiveness of this pilot project, we are taking those views into account, bearing in mind that we are committed to the idea of an open, accessible campus.”

Harald Kliems, a member of the Flat Bike Collective, said he is in favour of lifting the restrictions on bikes on campus.

“I strongly believe that it is possible and desirable to create a shared space on campus where pedestrians and cyclists alike can safely co-exist,” Kliems said.

Krayer von Krauss, who chairs the working group re-considering bike use on campus, said financial limitations pose a problem in terms of possible outcomes.

“Money will be an issue,” Krayer von Krauss said. “At this point, McGill could simply not afford, for example, to build a proper cycle path from one end of the campus to the other, if this is what was required.”

However, Nicell emphasized that safety is a bigger issue than the budget when considering the creation of a formal bike path across university property.

“It’s not a funding issue; it’s about what we’re here for as a community,” Nicell said. “We’re not anti-cyclist; we’re pro-safety. We have a history of very dangerous situations [involving bikes]. McGill is incredibly supportive of cycling, and we’ve created […] the infrastructure that’s required to support it.”

Next steps

This February, the city of Montreal will excavate McTavish St. to repair the water main leading from the city’s reservoir, which will leave the street closed off in sections until its

tentative completion date in Summer 2014. According to Adler, this repair is an ideal starting point to redevelop the surfaces and functions of lower campus in a more pedestrian-friendly and green way in the next few years.

“We were able to get the cars off lower campus, but we haven’t gone that next step to re-landscape and reorganize lower campus,” Adler said. “[McGill is] trying to partner with the city to make McTavish a showcase for how to re-develop urban streets as green spaces.”

In addition, McGill continues to look into options for expansion by keeping an eye on the real estate market in the area surrounding campus.

“We’re at the end of being able to be master of our own destiny because we’ve pretty well exhausted all of our own land resources,” Adler said. “So we have to be dependent on the marketplace, and we are actively finding out what’s available in the immediate vicinity and whether we can afford to acquire it.”

That could include purchasing nearby properties that are about to become available, such the Royal Victoria Hospital (RVH), which is set to be empty within two to three years once its facilities are relocated.

“There [are] a lot of people who have a stake in its long-term use, [but] there’s a wide-spread acknowledgement that McGill would be the best occupant of that space because we’ve been very good stewards of our land and our buildings,” Nicell said.

Since the hospital resides within one of Montreal’s cultural heritage zones, Nicell said the university would be under obligation to the city and the Quebec government to repurpose or renovate the RVH within the restrictions of such a zone.

Whatever the future holds, any decisions McGill makes regarding development—from purchasing a hospital to implementing bike gates—will be guided by McGill’s Master Plan.

“If it wasn’t for the Master Plan […] we’d be in a very different place now,” Nicell said. “Some people see it as a wishful document, but no—it’s guiding the goal over the long term so that every step we take leads towards our long-term vision.”

Possible Solutions:

(1) Bike path from Milton to McTavish

(2) Bike path up the main drag from the Roddick Gates.

(2) Bike path up McTavish.

Slow, controlled, yield-to-pedestrian biking everywhere else.

Safety through designated bike paths and no speed.

This would integrate well with Montreal’s excellent expanding network of bike trails.

Possible Solutions:

(1) choose a readable font