Project Consent shows us how to tell it like it is

In Project Consent’s new videos, dancing, laughing, and whistling genitalia tell us without a doubt that If it isn’t yes, it’s no. It might seem ridiculous that mature adults would need dancing, animated body parts to explain a rather serious issue, but although consent is commonly talked about, collective society still has a lot of progress to make. Recent high profile media cases, such as accusations against Kesha’s producer, Dr. Luke, and former CBC radio host, Jian Ghomeshi—in which both Ghomeshi and Dr. Luke were found to be not guilty of sexual assault—illustrate why we need to keep talking about consent. In response to the continued presence of sexual assault on university campuses, including McGill’s, campus initiatives like Rez Project and Consent McGill are presently working to promote consent; however, results haven’t been achieved on or off campus. Project Consent’s videos might seem silly, redundant, or overly simplistic, but this is exactly why we should embrace them.

The ongoing search to find the perfect metaphor for consent has no lack of source material: Be it a cup of tea, poutine, a bad haircut, or even pizza toppings, there are endless ways to illustrate consent. Of course, most people understand that you shouldn’t force a cup of tea on your houseguest—never mind your unconscious houseguest.

But while goofy and creative metaphors are effective at catching public attention and sparking discourse, the problem is that they are still only metaphors. Sometimes, metaphors can distract from the fundamental messages they are supposed to convey, and can make a serious issue seem like something as trivial as pizza toppings. Project Consent knows that if people are going to continue to seriously address the issue of consent, they need to talk about it as it is. We can no longer afford to sugarcoat, transform, or distort consent.

As is apparent in most sexual assault cases, consent is not easy to determine retrospectively. Cases often turn into he-said-she-said disputes, and lead to speculation by the media and observers more generally, who attempt to identify prior and subsequent behaviour on the complainants’ parts that might indicate whether or not acts were consensual. The ordeal of taking legal action often discourages survivors from coming forward and pressing charges, even though one wouldn’t think twice about taking legal action for most other physical injuries and emotional traumas.

Certainly, in the recent case against Ghomeshi, subsequent behaviour—including the fact that the women had sent him flowers or suggestive emails after the alleged assaults took place—was used to question the credibility of the women’s claims, especially when these details seemed incongruous with their stories. Many people seem to forget that consent is necessary at every single stage of an encounter or relationship, and just because a survivor continues contact with his or her assailant afterwards for whatever reason, it does not necessarily mean that sexual assault did not occur. Every time such a case falls into the spotlight, the necessity of being proactive rather than reactive is reinforced.

Initiatives such as Rez Project and Consent McGill aim to further conversations and understandings of consent on campus, but the issue cannot be resolved until the message reaches all members of the community. That survivors often wonder whether they are equally responsible for not having explicitly said “No” is extraordinarily disheartening. Project Consent’s videos can complement initiatives at McGill and hopefully reach a broader audience through their quirky but simple take on the issue. Project Consent reminds us: If it’s not yes, it’s no.

– Emma Avery

Project Consent is flash without substance

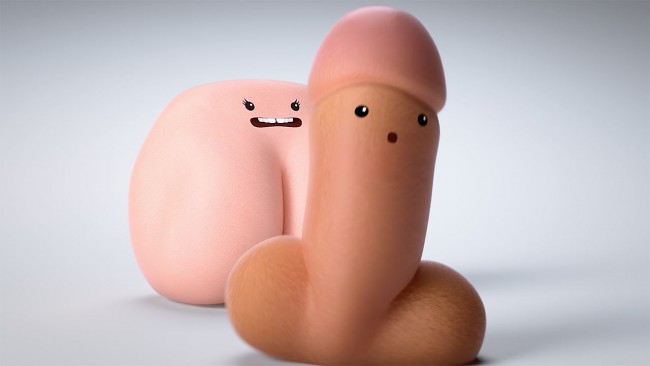

Recently, several videos appeared online as part of Project Consent, a nonprofit campaign that visualizes sexual consent. They are some of the most stultifying videos in existence, and they say a lot about popular culture’s viral influence on sexual manners in 2016. There are several iterations of the cartoon videos: In one, a personified penis dances towards a vagina, and in another a hand approaches a breast. These videos have gone viral. There were a few other versions of the video, but the gist is pretty evident. Penis hits vagina. Vagina says no. It was a far cry from the consent-by-tea, which asked “Would you like a cup of tea?” instead of “Would you like to have sex?” That video had explained, “If someone does not want a cup of tea, don’t force them to drink it.” How quaint.

There’s a lot to say about the video with the hands, butts, and vaginas, as many people probably do. What it boils down to is a lack of subtlety. This is not like the student in health class objecting to the metaphorical uses of the banana. Clarity is fine. But this was like watching a pornography clip in health class, or if the health teacher himself started groping a mannequin because words were too hard. It was beyond the pale—a slap in the face and a bucket of water over the head at once. A lack of subtlety, an unflinching gaze, and a starkly straightforward message: These define sexual education on the Internet, where the medium of the viral video is the message.

Think about what it means to use talking penises and vaginas as incredible visual panacea for the sexually depraved: It isn’t necessary. The tea skit, where tea was a metaphor for sex, was not too advanced for anyone. In health class, the banana was not too yellow to connote the human phallus, nor was the metaphor a perplexing scourge to responsible condom-use. Some people feel awkward about eating bananas in public, and most everyone can understand the tea video.

There is one simple reason that personified sexual organs appeared on the Internet, and it is not because there was any confusion that needed Project Consent to clear it up. It exists for the same reason pop music and viral videos exist—the people behind Project Consent latched onto the magical effect of popular culture to spread messages. In other words, they understood the need to achieve the status as viral for the video to become wide-reaching.

Pop culture is a format, a style, and a conduit for popularity. Even bizarreness is to its advantage, as it stimulates reactions and conversations. But more often pop culture is simple. Taylor Swift gets right to the heart of romance in only three minutes, and we don’t mind hearing her relatable ideas repeatedly. With pop, no one wants a symphony of subtlety or a lengthy development of ideas. They want simplicity, clear images, and flashing lights. Hence why Taylor Swift videos are such a phenomenon. Upload one, and whamo!—you get millions of views. The same applies for the Project Consent videos, which reduce the message of consent to animated genitalia. The result: A pretty useless video finds its way into your newsfeed. Brief shock-value (really, the detail of some of these 3D organs is bizarre) attracts popularity, but for it to work it has to be all format. All dazzle, no spark. It does not change people’s perceptions—it just attracts their attention.

Project Consent claims it is doing something new, breaking down walls of misconceptions: Hogwash. The only walls it is breaking down are our own feeble barriers to insipid Internet videos. The point of popular culture is to say simple things and use images effectively. Project Consent did this, but it went too far in the direction of images, saying absolutely nothing new.

Ben Cohen-Murrison