Every minute, there are 3,600 more photos on Instagram to like—and that’s not even including images posted on Facebook. Inspired by the volume and speed of information generated online, the browser Qmee, in collaboration with Social Media Agency mycleveragency, pulled together a detailed infographic to illustrate what transpires in the minute you spend turned away from your screen.

The vast amount of digital information available online is growing more rapidly each year. This growth places us in a unique position; for the first time in history, the rate at which news travels around the world has exceeded that of the traditional media. Websites like Facebook or Twitter play off of humanity’s documentary instinct, allowing individuals to quickly share their experiences with members of the Internet community all over the globe.

However, with this culture of citizen journalism comes the question of credibility. If everyone can be a ‘journalist’ online, how much of the information posted can we trust as entirely true?

When an earthquake of magnitude 7.6 hit Costa Rica on Sept. 5 2012, the shock waves took about 60 seconds to reach the capital of Nicaragua, Managua. Within the next 30 seconds, the first tweet reading “tremor” appeared online.

In the case of recent events in Tahrir Square, where former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak announced his resignation, Twitter exploded with tweets documenting the event. This form of social media played an important role as a means of communication within a volatile environment, as journalists were forced to leave the area due to safety concerns.

Journalists paid particular attention to following certain ‘Tweeple’ (Twitter people), designating them as ground-level sources for the events unraveling moment by moment. Knowing which of those profiles were credible was quite a task—there were tens of thousands of tweets floating around as the situation transpired.

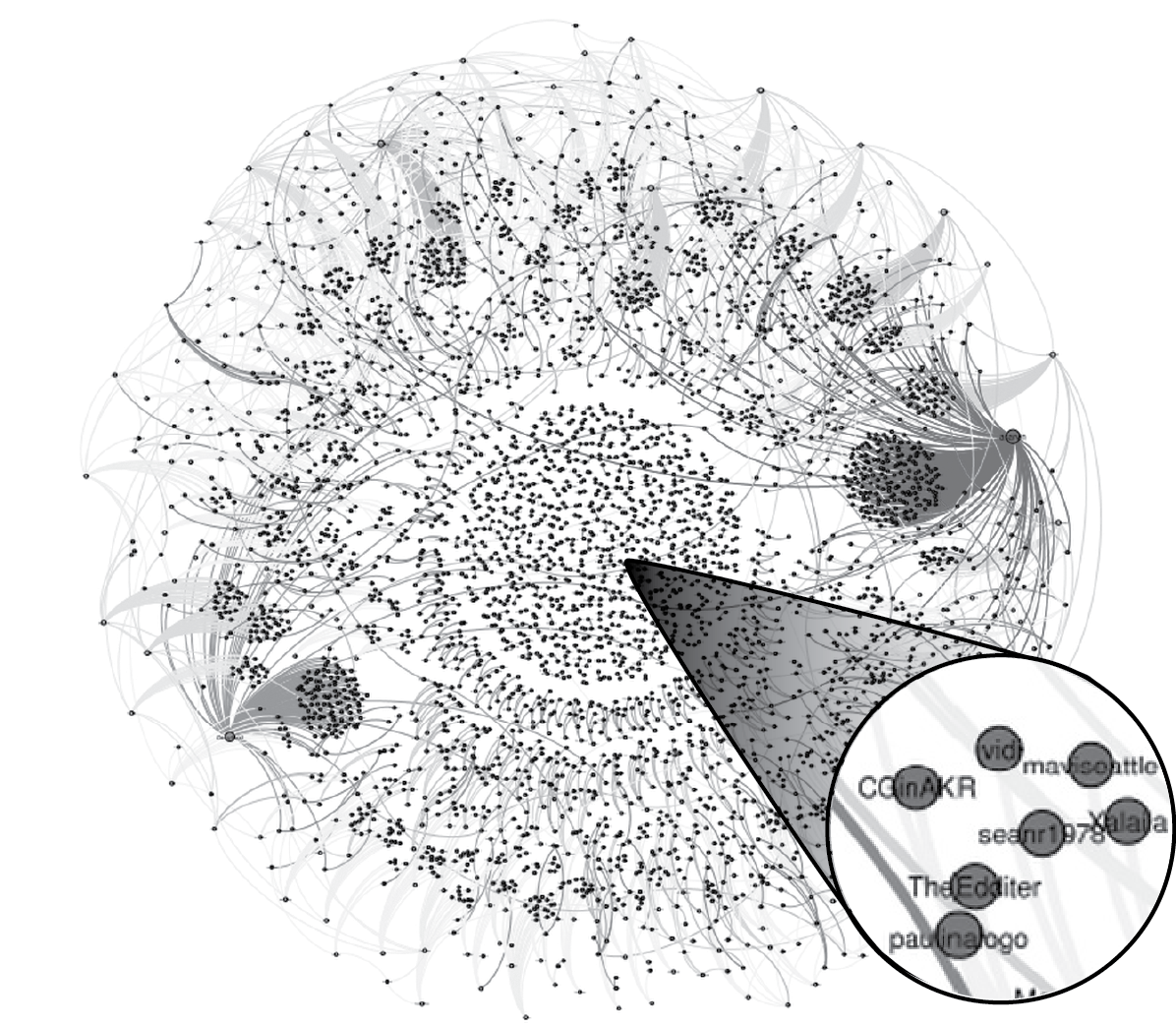

To address this issue, programs were used to track social media and verify its credibility. Andre Pannison, a network scientist at the University of Turin, created a visualization of all the tweets with the hashtag #jan25, the suspected date of Mubarak’s resignation. Each tweet is represented as a node and ‘re-tweets’ are mapped as lines between these nodes through the use of a program known as a Gephi Graph Streaming plugin.

By analyzing the image, the credibility of the source could be inferred from the number of lines emerging from each node, proving an amazing tool in the hands of journalists striving to paint an accurate portrait of the situation as events progressed at Tahrir Square.

Evidently, there is an interesting shift in the dynamics of content-generation and consumption. With the widespread capacity of sharing thoughts online, there is an abundance of information in times of crisis. The role of the journalist has expanded to not only covering events through one’s own eyes, but also acting as filters and synthesizers of news from relevant and credible social media sources.

We, as students and consumers of web-based social media, are responsible for contributing to and receiving a large portion of social media—and often credibility—questionable. One method of addressing this issue is looking for alternate sources confirming the information or reporting a similar story.

This summer, when a sinkhole developed on Ste. Catherine while construction was in progress, social sites were abuzz with a particular photograph of the incident that seemed to have originated from the camera of a passer-by. It was shared by Virgin Radio’s Facebook page and then by McGill students. Over and over again similar photos were posted online, all showing different angles of the same sinkhole shared on Virgin Radio’s page. In this case, the consistency and volume of evidence established the credibility of the incident.

In contrast, last year McGill was abuzz with people claiming they had spotted Tom Hanks on a private tour of the campus in relation to enroling one of his children at McGill. This time around, not only was there no photographic evidence, but also a lack of consistency with respect to reports of his clothing and tour group; this diminished the story’s credibility.

As consumers of social media, we are responsible for critically assessing the credibility of information posted online. Even then, the facts remain blurry, and we must tread a little more carefully before accepting any information online as the truth.