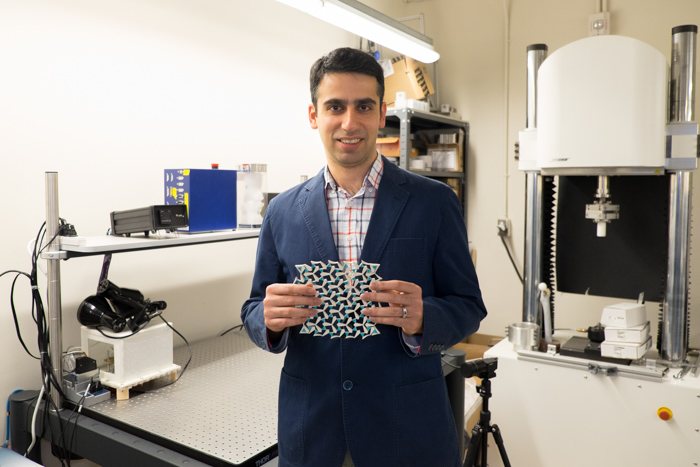

On March 21, McGill University’s Facebook page shared a video that demonstrated a unique type of material called an auxetic, expanding while being stretched. The metamaterial, designed Dr. Ahmad Rafsanjani, a member of the Pasini lab in McGill University’s Faculty of Engineering, is unique because when it is stretched, it becomes wider and longer. Conventional materials such as metals or plastics, on the other hand, contract in the direction lateral to the force exerted upon them. That is, they get longer in the direction they are pulled in, and shorter in the opposite direction—longer and thinner.

Due to this unique property—defined in mathematics as exhibiting a negative Poisson’s ratio—engineers categorize auxetics as a class of metamaterials that possess mechanical properties above and beyond that of conventional objects.

Bistable auxetics are desirable in any industry that requires smaller packaging. They may have applications in medical stents, which are used to treat narrow or weak arteries. Traditionally, a metal or plastic tube inserted into a blood vessel is used keep open previously blocked passages. Having a flexible material will enable smaller arteries to be treated with greater precision. Additional applications include satellite panels, where smaller packaging is essential in delivering the payload into space.

Scientists and mechanical engineers have studied auxetics extensively. As a result, the conventional square auxetic, a ‘base’ model for this class of metamaterials, has been very well described. In order to stay in an expanded form, conventional auxetics require a constant and continuous force to be exerted upon it, and this unfortunately makes the material difficult to commercialize.

DesignDaily: Material that can grow when stretched is inspired…

Inspired by Islamic art; a group of researchers at Canada’s McGill university have engineered a new kind of stretchable material that can grow when stretched.A ‘metamaterial’ that when pulled in one direction, expands also in a lateral direction. In other words, when stretched, the material becomes wider, rather than just longer and thinner.Video via: New Scientist Credits: A Rafsanjani/McGill University

Posted by DesignDaily on Monday, March 21, 2016

On the other hand, the auxetics designed by the McGill team is bistable. Bistable auxetics require no such additional force to stay in an expanded conformation, and consequently possess myriad of applications ranging from aerospace to biomedicine.

“Before [my design], the only bistable auxetic that has been described were complex origami patterns,” Rafsanjani said. “They were hard to make. Graduate students sometimes spent days just folding the patterns.”

Researchers first discovered the bistability of origami structures in a paper published in Advanced Materials in March 2015. And the design developed by Rafsanjani can be created using a laser cutter in less than an hour.

“The beauty of purely mechanical systems is that they are scale-free,” Rafsanjani explained. “Essentially, a model developed in a lab can be changed into any size for any practical application.”

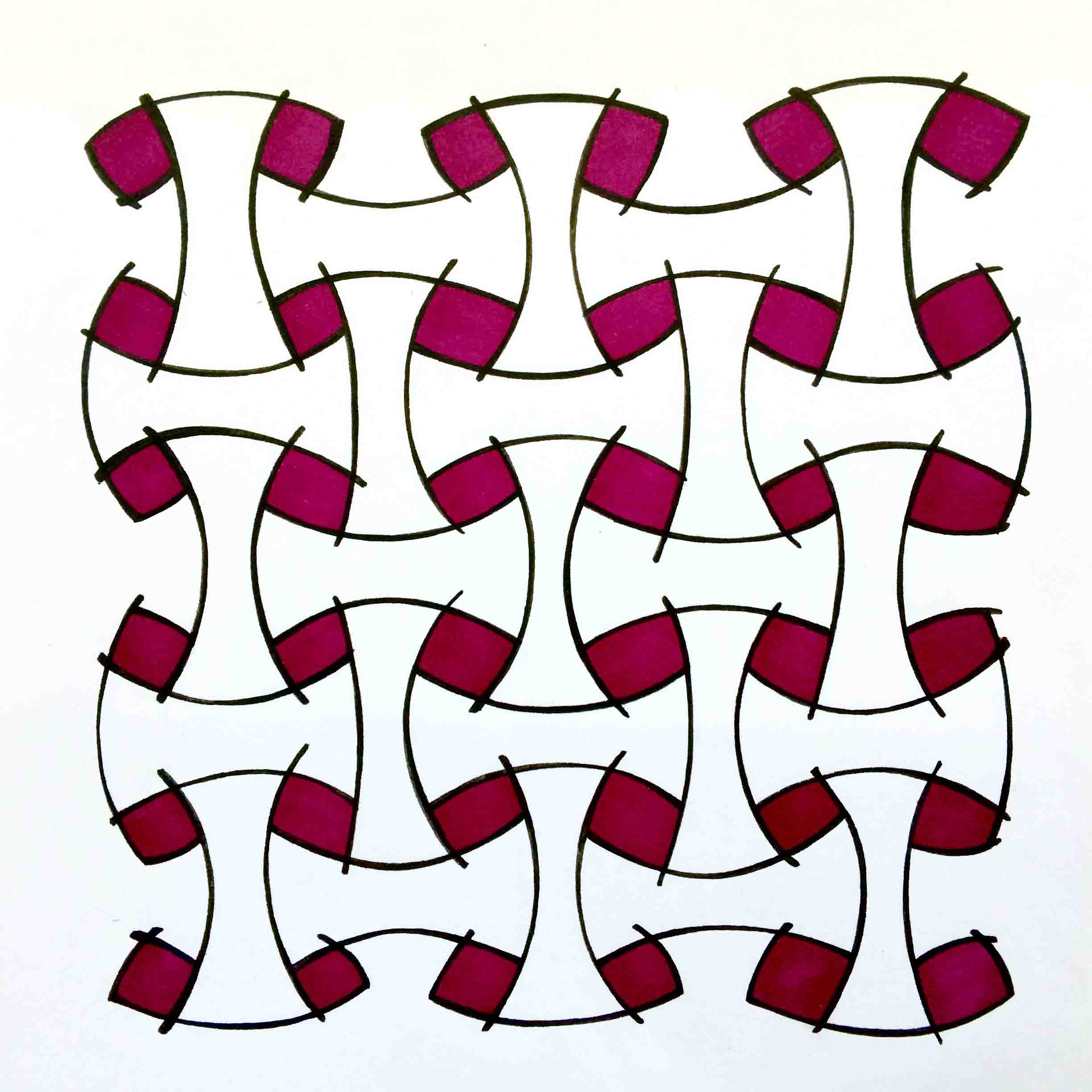

Born and raised in Iran, Rafsanjani attributed his geometric designs to Islamic art, specifically the patterns found on panels of a 1,000-year-old Iranian tomb; however, Rafsanjani cites all forms of art as sources of scientific inspiration.

“Throughout my life I attempt to find elements that inspire me” he explained. “Artists are not bound by [the same] practical and physical constraints as scientists.”

It appears that art, as an element of inspiration, is a recurring motif in Rafsanjani’s works. In a paper about metamaterials published in 2015, Rafsanjani cited artist Ron Resch in his introduction.

However, Rafsanjani’s description of his materials as being inspired from Islamic art has been met with criticism. Some have argued that Islamic art is not an all-encompassing term and that science and art should not be mixed.

“I could very well have said ‘Persian Art,’ or ‘Iranian Art,’” Rafsanjani said. “Of course this would have been a lot less controversial. But the geometric patterns that I used are part of an artistic theme synonymous with Islam. To use another name would simply be not true.”

Regardless of where he draws his inspiration from, Rafsanjani plans to continue his scientific work.

“I am dedicating my life to the pursuit of scientific achievement,” he said.

Pingback: Our work on BBC News - Pasini Group