A newly-opened exhibition in the Strathcona Anatomy and Dentistry Building offers researchers, students, and members of the public the opportunity to explore a fascinating array of anatomical specimens, dating back almost 200 years. The Maude Abbott Medical Museum provides visitors with insight into the rich history of medical studies at McGill as well as the rare opportunity to see preserved organs and other body parts up close.

The history of the artifacts goes back as far as McGill itself. Among the antiquities are specimens dissected by the first members of the Faculty of Medicine, including Sir William Osler. Known as the Father of modern medicine, Osler founded both Johns Hopkins Hospital and the History of Medicine Society in London, and he pioneered the practice of exposing medical students to bedside clinical training.

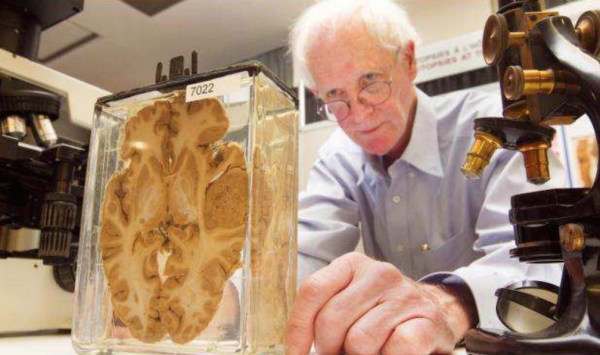

“These are some of the oldest things that McGill University has,” Richard Fraser, the director of the museum, said.

The museum’s namesake, Maude Abbott, took original charge of the collection in 1898. Abbott was among the first women to graduate with a BA from McGill. However, as a woman, the university refused her entry to study postgraduate medicine. She studied elsewhere, graduated at the top of her class, and returned to McGill. Still barred from holding a faculty position, Abbot took on the role of assistant curator of the collection.

Her work with the museum and its artifacts fuelled her success as a pathologist; by collecting and cataloguing heart specimens for the museum, she was able to publish groundbreaking works on congenital heart disease, becoming an international authority on the subject. Her personal success was mirrored in the success of her museum.

“She made it one of her life jobs to develop the museum, and she did,” Fraser said. “She developed it into one of the premier medical museums in North America.”

However, despite Abbott’s able custodianship, the specimens have not been easy to preserve. Following a devastating fire in 1907, intradepartmental conflict over the running of the museum, and Abbott’s passing in 1940, the collection was neglected and forgotten.

This remained the case until Fraser stepped onto the scene. When the International Academy of Pathology celebrated its centenary in 2006, many of the specimens were brought back into the light of day in a temporary exhibit recreating the historic museum. As Fraser became better acquainted with the specimens, he came to appreciate their value, both as historical artifacts and as anatomical teaching materials. He was convinced that they were worth preserving and worth sharing. Fraser’s passion for the museum has culminated in the new exhibit, finally uniting the collection under Abbott’s name.

The exhibition brings together historic and contemporary approaches in the fields of anatomy and pathology. The museum makes use of tablets dotted among the historic display cases, showing informative videos on, for instance, how modern imaging technology can help visualize internal anatomy. These aids help contextualise the specimens as artifacts of their time, clearly juxtaposing the old with the new.

As was the historical norm, specimens were often collected from patients without any explicit permission. This can make their display a sensitive issue, which, Fraser argues, makes it pertinent that they are displayed in the correct context. According to him, part of an informative experience involves understanding the history and methods of the study of medicine, rather than merely the pathological curiosities in themselves.

The refurbished Maude Abbott Museum is a unique experience that brings together the past and present. The hope is that the collection that Abbott worked hard to curate will be appreciated as—in Dr Fraser’s words—a “jewel of McGill.”