“It’s a hard three letters to absorb. It’s a turning point in one’s life,” was how Charlie Sheen described his diagnosis with HIV in an interview with NewsTalk.

After revealing his illness in December of last year, Sheen faced multiple lawsuits from ex-sexual partners claiming he didn’t inform them of his infection. In both the United States and Canada, it’s a criminal offence to be HIV-positive and have sex with someone without informing them of their diagnosis.

For much of the HIV-positive population, infection remains an unspoken secret. Diagnosis with HIV was nearly a death sentence during its peak outbreaks in the 1980s. Today, the disease can be well-treated and controlled. Through what’s known as cocktail antiviral drug therapy, patients are administered a variety of drugs that greatly lower viral load—the number of virus particles in the body—and reduce infectivity. HIV infects and kills important immune cells called T cells, often leading to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and thus allowing opportunistic infections to thrive; however, many HIV-positive patients are now able to live normal lives, with their status never progressing to AIDS.

Still, the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS persists. In North America, infection continues to be associated with death, despite the landmarks made in antiviral therapy. HIV infection also remains attached to taboo topics, like homosexual sex and intravenous drug use, and is often therefore associated with irresponsibility or moral fault. Although HIV has been shown to spread primarily through heterosexual sex, infection also continues to be associated with homosexual behaviour.

Unfortunately, this stigma is not just a sociological phenomenon; it has huge impacts on the epidemiology of the virus. Dr. Mark Wainberg, director of the McGill University AIDS Centre explained that one of the primary hurdles in ending the HIV epidemic is getting people to come forward for testing.

“Studies have shown that a majority of at-risk individuals in some countries [like the UK] don’t know they are infected because they have never been tested,” Wainberg said. “This is probably due to the perceived stigma attached to an HIV diagnosis.”

As of 2014, the Public Health Agency of Canada stated that one in five HIV-positive Canadians were unaware that they had HIV. This represents approximately 16,000 Canadians who could be effectively treated, and countless others who could avoid infection.

Lowering viral load through therapy can prevent HIV transmission; however, doctors cannot begin treatment unless they know who is infected.

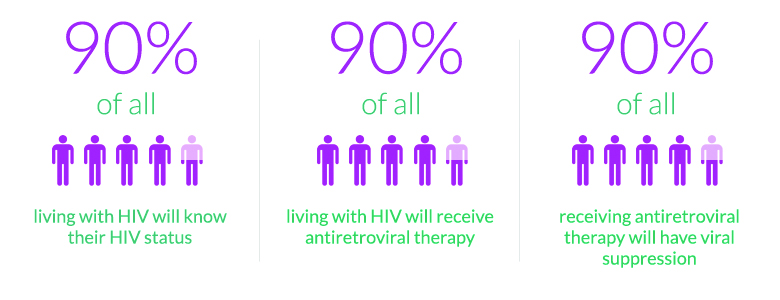

“The WHO [World Health Organization] has established 90-90-90 guidelines to be accomplished by 2020,” Wainberg explained. “Identify 90 per cent of people who are positive, treat 90 per cent of those, and bring 90 per cent of those who are treated to non-detectability of viral load (making them non-infectious). The attainment of the initial 90 per cent goal will be by far the most difficult.”

To meet this goal, Wainberg proposes paying people to be tested, as a means of incentivizing them. An additional way to promote diagnosis rates may be to combat the stigma associated with the disease. Either way, it is clear that proper awareness of the modern HIV/AIDS epidemic is vital, as this stigma may be one of the most dangerous epidemics of our time.

Paying people for testing is definitely a good strategy but on a larger perspective (especially with the motive of replicating the strategy in developing world) there could be some implications of the same-such as in a country like India where government has already reduced the funding for HIV related interventions in its annual budgets, incentivizing people may not be very cost effective. Also, in order to reach the intervention to the MaRPs (Most at Risk Population) there will be need to segment people on the basis of prevalence. One suggestion to the government and funding agencies could be that they can pilot test the suggestions first with MaRPs.