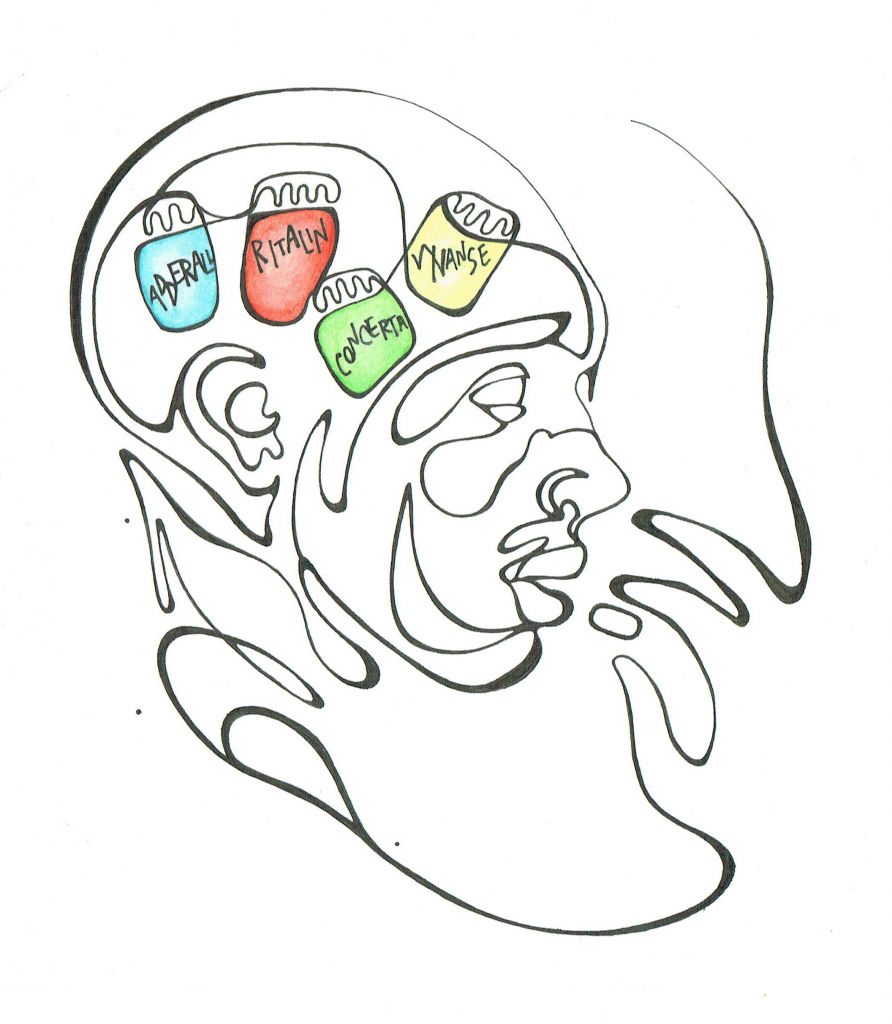

The use of psychostimulant drugs like Adderall, Ritalin, and Vyvanse has become increasingly routine for some university students striving for success. In fact, some studies report up to 34 per cent of U.S. college-level students use non-medical psychostimulants for increased academic performance. Use also seems to vary by social group. For a cohort of fraternity members, this number was found to be as high as 55 per cent.

Pyschostimulants include a broad class of drugs normally prescribed to treat symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity common in patients with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Some of the most commonly used stimulants are derivatives of amphetamines. For example, Adderall is a mixture of two mirror-image organic molecules—called enantiomers—dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine.

Amphetamines work by binding to trace amine associated receptors (TAARs) in the brain, triggering the release of natural neurotransmitters like epinephrine (adrenaline) and dopamine from specialized neuronal compartments, called synaptic vesicles. These neurotransmitters increase signalling between neurons, and consequently enhance cognitive activity. This results in increased focus and attention.

For patients with ADHD, regular use of stimulants generally shows a low rate of negative side effects. Thus, prescribing stimulants to those with ADHD seems like a clear solution to treating symptoms. The issue of nonprescription use of stimulants, however, is much less black and white.

Interestingly, stimulants are generally found to have very little effect on healthy individuals, with results comparable to other study techniques like physical activity or meditation. A 2013 study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania found that students merely perceived the drug as strongly enhancing their cognitive ability. Discussing the ethics behind stimulant misuse, consequently, might be a moot point, as they may not actually provide an unfair advantage over other students. Still, others disagree. Biomedical ethicist Dr. Cynthia Forlini from the University of Queensland Centre for Clinical research, explained that while the overall effects of stimulants on students is generally low, the results may vary drastically between individuals.

“There’s a phenomenon [called] the enhancement ceiling,” Forlini said. “You can only be enhanced so far. A higher performing individual will not get a big benefit from these drugs; however, if your baseline performance is lower, these drugs might help you much more. It’s an interesting idea to frame the debate around—an optimizing or normalizing of performance, bringing people to a certain level that cannot be surpassed.”

The issue to be addressed then, is how to frame the debate behind stimulant misuse.

“If you’re tackling something like prescription abuse, the connotation is very different than if it’s [an] enhancement or a lifestyle choice,” Forlini explained. “You’re not going to talk about fairness—it’s whether or not this is cheating. If you frame it as a lifestyle choice, then maybe—although you’re not supposed to be doing it—this is a choice that you have to help attain your goals.”

Discussing the topic in a neutral light appears to be key to reasonable debate. This avoids the implied connotation behind the different terminologies.

“‘Non-medical prescription use of stimulants’ is a mouthful, but it doesn’t have that ethical connotation of implied benefit, which I think is a problem because the effects just aren’t there for everybody,” explained Forlini. “You’ll find very different effects across individuals, so the idea of enhancement doesn’t always stick. It might not make sense to talk about enhancement if you’re not seeing those effects.”

Ongoing research in bioethics seeks to find the causes behind stimulant misuse in order to resolve this issue. It remains unclear whether it is up to students to seek academic help, physicians to use more caution in prescription, or institutions to consider the question: Why are our students using stimulants in the first place?

Rubbish. My husband and I (and lots of our friends) both loved the “Dexies” we used to take in college, mainly for studying but also for stressful times. (eg, I dreaded having to speak in public; one of these pills not only got me though it but also made it even enjoyable!) We could not be more unalike. Husband’s a well-rounded, popular, positive, upbeat, witty Tom Sawyer kind of guy; I’m darker, cynical, depressive. I’d LOVE to be able to take these pills every single day for the rest of my life; it would be a huge blessing. (I’m on SSRI’s–v. different).) The ONLY question is (should be) whether it would be dangerous to my health, lifespan. I don’t understand why ADHD’s can take them with no harmful effects. I’d love more information on this topic.

I happen to believe, based on close observation, that ADHD is primarily caused by life situation, modern parenting to be precise. Surely many of those kids whose “ADHD is in fact caused by childhood stress and poor parenting are taking the stimulants even though their problem is psychological. Are they being harmed by the pills? What is the harm? It’s an important question to me because I’m definitely not ADHD but could greatly benefit from stimulants in other ways.