“Fans have always had opinions,” Jay Baruchel said. “But, it used to be that the only people that would hear them were other fans or, potentially, the poor bastard that has to host the postgame show on whatever radio station.”

In this instance, Baruchel was alluding to social media specifically, but the number of ways to express feelings about one’s favourite sports is growing. Baruchel continues to use as many of them as he can.

The 2012 film Goon, which he co-starred in and co-wrote with McGill alum Evan Goldberg, is one of the most overt examples of the Canadian actor’s obsession with hockey. Baruchel, also known for the 2013 film This is the End and the How to Train Your Dragon franchise, is consumed by his love for the Montreal Canadiens. To put his self-proclaimed ‘religion’ into words, Baruchel has written a book about his fandom. Born Into It was released on Oct. 30.

When he spoke with The McGill Tribune over the phone, Baruchel was in Montreal for a few days for his book tour. Now that he lives in Toronto, Baruchel’s itinerariesare always packed when he returns to his hometown.

“I make sure I eat all the food I can’t get in Toronto,” Baruchel said. “And, so, I was very pleased and […] surprised when we got off the VIA Rail on Thursday, and my fiancée said, ‘Let’s go to St-Hubert,’ and I was like, I would never have the balls to ask or to suggest that as a place where we could have supper, but I will definitely take the opportunity.”

St-Hubert is a favourite of Baruchel’s; he effusively praised the local chicken chain during his appearance on Jimmy Kimmel Live last year as well as in his new book. In his prologue, he describes the experience watching the game at his place, waiting for St-Hubert delivery. It’s a nostalgic moment of writing, that feels timeless for sports fans.

“Finely-tuned chicken instincts turn all our heads to the front window, and we are now legitimately excited because we are all legitimately hungry,” Baruchel writes. “A little bright-yellow hatchback has just pulled up in front of my house, and within it lies chicken that will soon be in our stomachs.”

Baruchel has a knack for describing these little moments from his hockey story. In an early chapter, Baruchel pinpoints his first hockey memory: Watching a Canadiens game at age three with his father and choosing to cheer for Les Habitants.

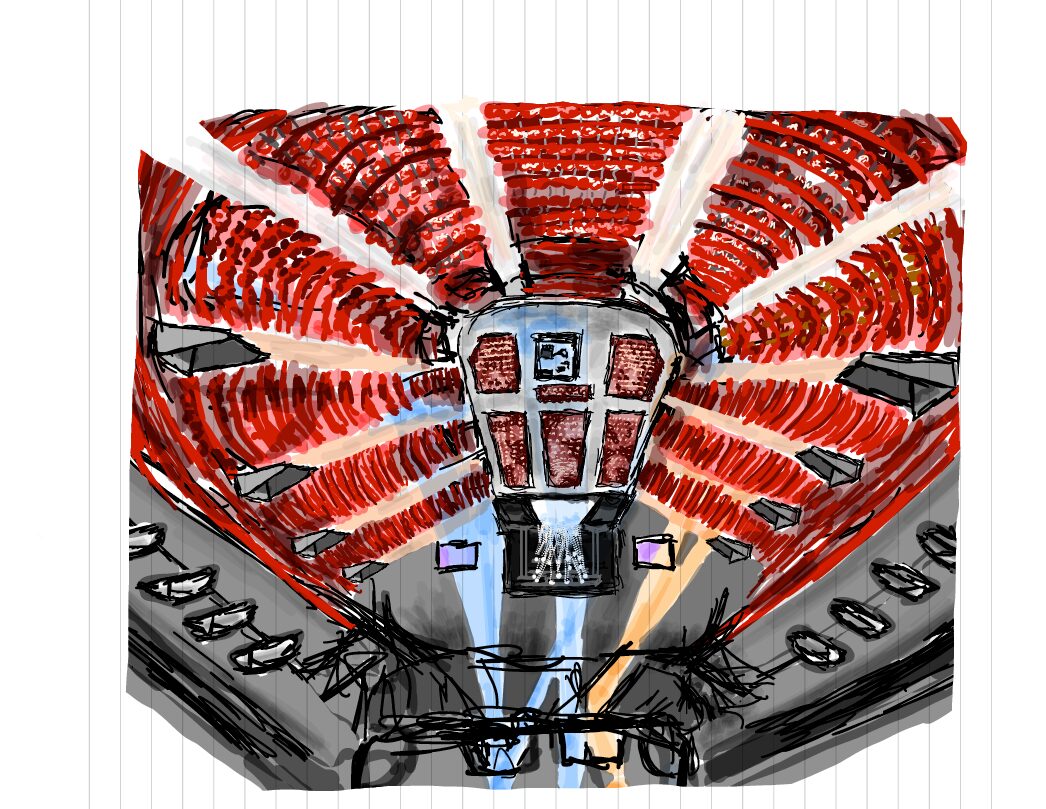

“Granted, I’d picked the Habs because red was, and still is, my favourite colour,” he writes. “But, I also know that the reason I love the colour red is because my parents always painted my bedroom stuff red. Because they were Habs fans, and I was always going to be a Habs fan. I never had a choice. I was born into it.”

Much of sports fandom starts out similarly to the way Baruchel remembers his own fandom starting: As a matter of nature and nurture. Family dynamics inform and often create fandoms. However, family can divide fans, too.

“[Sports] can […] do the same thing as politics, just probably softer, I think,” Baruchel said. “At the end of the day, it’s just hockey. But, I think it can drive a wedge sometimes.”

Baruchel moved to Toronto a few years ago for work. His relationship with his new city is complicated, largely because of the Canadiens’ dreaded rival, the Toronto Maple Leafs. In Born Into It, Baruchel writes mock hate emails to the Leafs and two other Canadiens rivals, the Boston Bruins and the now-defunct Quebec Nordiques.

“What seems to cut through and really register with people and seems to be sort of a part of everyday Habsism is our enemies,” Baruchel said. “We are Habs fans because we like the Habs, but we are equally Habs fans because we hate the teams that the Habs hate.”

That makes his own situation more convoluted, since the number of Leafs fans in his own family is only growing, as he marries into his fiancée Rebecca’s family of Leafs fans.

“For me, there’s a certain aspect of Habs fandom that requires being a troll,” Baruchel said. “There’s this […] petty chip on our shoulder that we have that a lot of other teams don’t have [….] The first time I met all of her extended family last Christmas, I was […] wearing a Habs scarf the whole day. So, in all the photos, I’m wearing my dumbass scarf, and it definitely informed all of the introductions to everybody.”

Baruchel’s love of hockey is pure; he sees it as the most beautiful game ever created. Further, he feels that if ever there were to be something truly symbolic of being Canadian, it would be hockey. The sport embodies some of what Baruchel sees as the key Canadian values.

“This is a country […] where nobody likes to paint anybody with [a single Canadian identity], but if I was to […] distill Canadianness into […] adjectives, it would be […] humility, work ethic, and toughness,” Baruchel said. “Canada’s all about doing what needs to be done when you need to do it. Because if you don’t, you can’t fucking drive your car because it’s fucking fused to the sidewalk in a cocoon of ice.”

Baruchel barely touches upon his Hollywood career in Born Into It, noting that those stories could fill a book of their own. Instead, he dedicates whole chapters to topics like hockey fighting—tying in the thread of his Goon movies, which feature a minor league hockey fighter as their protagonist.

Baruchel struggles with his feelings about fighting, since he does not have to suffer the consequences. As a fan, though, he feels that hockey fighting exemplifies Canadian traits.

“I think it’s like a dirty little secret that nobody wants to name,” Baruchel said. “Hockey fighting is as Canadian an experience for those participating in it, for those watching it, as anything [….] I think that there’s something […] honest and […] kind of quaint about trying to solve your differences with your two fists, real simply.”

To Baruchel, though, Canadianness lies in what happens after the fight.

“Look at how the majority of […] those boys relate to one another after they drop the gloves,” he said. “After it’s all said and done, it’s a lot of helping each other up off the ice [….] It’s something that’s in us and has always been in us.”

Baruchel points out that even though the public ignores it in favour of the overarching Canadian stereotype, the Canadian fighting spirit has been present throughout the country—hockey is just its outlet.

“The first time we played […] hockey indoors, there was a donnybrook [a fight],” Baruchel said. “It doesn’t necessarily dovetail, and it might seem incongruous with progressive Canada, but I don’t think it is. I think we found a place to put it.”

Baruchel believes it is a good thing for Canada’s teams to be at odds with each other.

“I know Toronto and Montreal on a Saturday night is […] as close to […] a storied cultural institution as we have in this baby country,” Baruchel said. “And, I think that Canada is better when the Habs and Leafs are better and are at each other’s throats, and, if Canada is better, then hockey’s better.”