International hockey tournaments are in full swing around this time of year. The World Junior Championships take place around New Year’s, the World Championships are in the spring, and every four years, we get to see hockey at the Winter Olympics. Needless to say, it’s a good season to be a hockey fan. While these tournaments are exciting, there has been one highly unpopular event that has increased in frequency to the point of critical mass in recent years: The shootout.

Shootouts suffer from one fundamental problem: They don’t provide a satisfactory finish to hockey games. A disappointing ending takes away from the excitement of the game’s preceding action. The shootout takes what is fundamentally a team sport—built on teamwork and collective skill—and turns it into an individual show. Teamwork is imperative in hockey, so to resort to the individuality and fluke outcomes that shootouts encourage seems inconceivable. Yet, they remain prevalent. It’s time for the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) to consider scrapping and replacing shootouts.

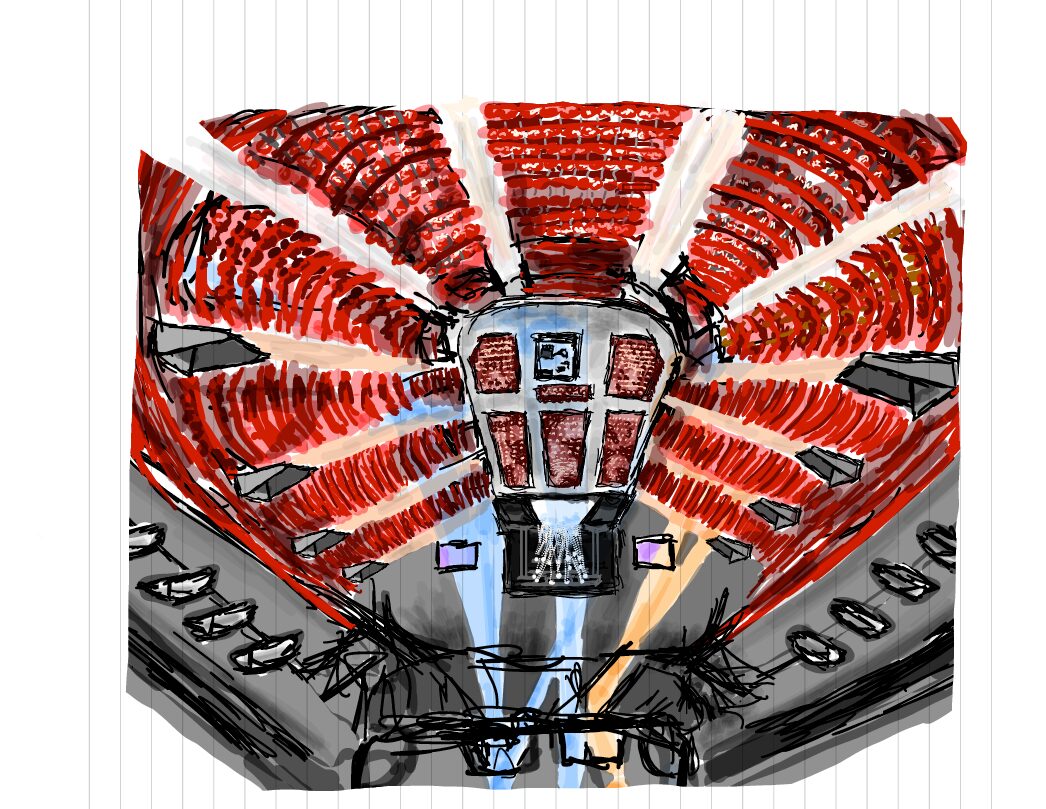

At the 2017 World Junior Championships in January, strong Canadian and American teams faced off in the gold medal game in an exciting match that ended in a tie, forcing overtime. After a scoreless-but-exciting overtime period, the game went to a shootout, essentially a skills contest that didn’t necessarily represent the competition as a whole. At the World Championships five months later, history repeated itself when the gold medal game between the North American rivals ended in another shootout. Most recently, the latest iteration of the infamous Canada-U.S. rivalry in women’s hockey ended in a shootout at the gold medal game of the PyeongChang Olympic Games.

Something needs to be done about this long standing issue, but few have agreed on what. The most logical conclusion is to get rid of shootouts outright; however, this decision can create problems in and of itself, such as unnecessary strain on athletes and the fact that few tiebreakers besides overtime would be more exciting or team-oriented than shootouts. New overtime rules, however, have the potential to decrease the amount of shootouts. For ideas, the IIHF can look to the NHL.

In 2015-2016, after poor reception to the shootout format, the NHL switched from its previous four-on-four overtime format to three-on-three. With fewer players on the ice, it became much easier for teams to create scoring chances, and the goals started to flow. The number of games resulting in shootouts fell from 170 to 107 in just one season. Fifty-six per cent of games that required extra time in 2014-15 ended in a shootout, while just 38 per cent did a year later.

Furthermore, in the NHL, these three-on-three periods last no more than five minutes. The IIHF could introduce three-on-three overtime, and even double that length—from five minutes to 10. Shoutouts wouldn’t become extinct, but with a limited number of games—as is the case in a tournament—the likelihood of a gold medal coming down to a shootout would decrease considerably. Otherwise, the IIHF could turn to the NHL playoff overtime system, where the game continues in 20-minute periods until someone scores. However, since tournament games typically take place in quick succession in the same building, this option is only viable for the gold medal game.

The frequency of shootouts in international competitions has gotten out of hand, and the IIHF needs to address the problem. The World Championship qualifiers take place in April, and the tournament itself follows in May. The stream of international tournaments is practically infinite, so the IIHF has plenty of opportunities to make changes. The puck is in the IIHF’s zone—and it’s their turn to play it.