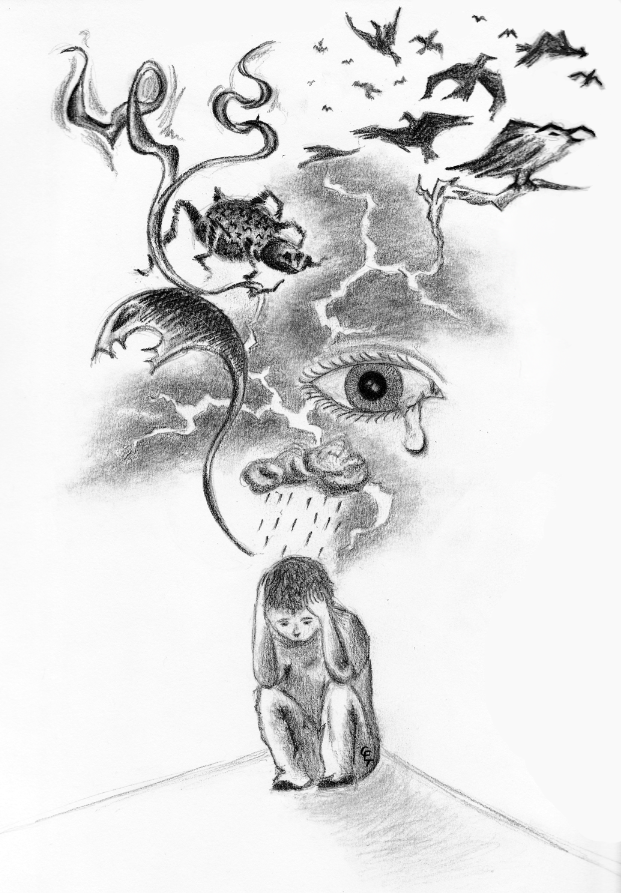

Sports culture dictates a very specific image of what an athlete should be. In the worst cases, this can cause emotional trauma in those who play sports, preventing them from expressing their emotions or asking for help when they feel overwhelmed. Neither fame nor money can protect someone against mental illness, which is why a support system needs to be put in place for these athletes.

The demand for high performance occurs both on and off the field. Athletes lay the blame and responsibility for success—particularly in individual sports—on themselves. Playing a sport is more than just about the game itself. The need to be accepted into a team environment on a social level can be so great that a player may sacrifice his or her own well-being for the benefit of the team. For example, when the Miami Dolphins’ offensive tackle, Jonathan Martin was left racist and abusive messages by teammate Richie Incognito, Martin was deeply affected by the bullying and left the team due to depression. Martin was initially afraid of voicing his unhappiness in fear of retribution from his teammates.

The general nature of professional sports can be another source of depression, as athletes face the inevitability of a short, yet intense sporting career. Athletes train for years in preparation for one particular event, and once that event passes, they may lose their sense of purpose. This same feeling occurs with an early career-ending injury. In both cases, athletes are left unfulfilled after their careers are over. The sport has consumed their entire life for years, leaving a void once they can no longer play. It may take professional help—such as talking to a career counsellor—for athletes to realize they have other options.

While career-ending injuries are oftentimes conspicuous in appearance, there is another type of injury that is more covert but is nonetheless a direct cause of depression: head injuries. NHL players Derek Boogaard, Rick Rypien, and Wade Belak all committed suicide in 2011. Although the official causes of death were linked to mixing alcohol with painkillers, Rypien and Belak were depressed, and Boogard suffered from severe trauma. Serious blows to the head catalyze a change in the hormonal balance of the brain, which causes depression to occur. Furthermore, addiction to depressants such as painkillers and alcohol—which can be caused by the long-term side effects of concussions—perpetuate the depression. Unfortunately, the pressures to play through injuries, the expectations of coaches and teammates and the overall ‘culture of resistance’ present in sports stopped these players from properly seeking the help that they required.

The pressure to play while injured and to sacrifice one’s body goes beyond the athlete and the team to the spectators of sporting events. Fans love the thrill of a good fight in hockey, or a solid tackle in football; these are the reason that there is an enforcer position in hockey. There is an entertainment value to sports that athletes must try to uphold. However, in doing so, they put their bodies and minds at risk

These same spectators will argue that athletes know what they are getting into when they play a sport. Players do indeed acknowledge the risk of participating, and they get richly compensated for these risks. Yet depression is a consequence of sport, just as shin-splints, broken bones, fame, and fortune can all result from playing. There is a lack of support in the mental stability of players in this high-pressure environment. If the idea of having an on-call physiotherapist is considered necessary in the sporting world due to the amount of injuries, then players should have the same accessibility to a psychiatrist—because mental health problems are just as common.