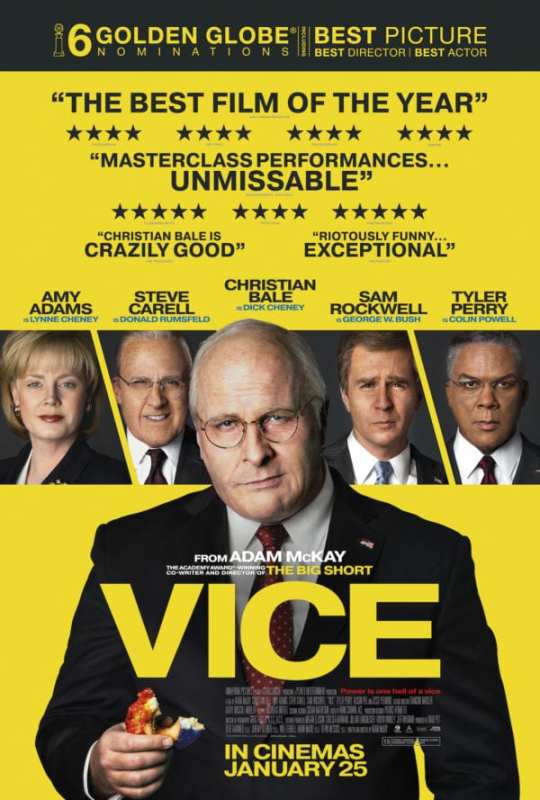

In a moment when Trump’s presidency is often perceived as a low point in American democracy, Adam McKay’s Vice shows how Trump is simply following in the footsteps of older, more tactful Republicans predecessors. Christian Bale depicts Dick Cheney with undisguised bias as a man of pure evil, even thanking Satan at the Golden Globes for his help in mastering the part.

Vice employs the same style as McKay’s last success, The Big Short (2015), an absurd and comic depiction of the decidedly unfunny 2008 financial crisis. Vice covers similarly dark subject matter, following former vice president Dick Cheney’s ascent as the man responsible for fomenting mass-hysteria, the invasion of Iraq, and a dystopian surveillance state under the Bush administration. To be sure, Vice is less comedic when compared to The Big Short, perhaps because of its focus on Cheney as a singular evil, in contrast to the faceless financial system. In any case, Bale mastered Cheney’s threatening inhalations, hard stares, and pained grimaces to produce a protagonist who disgusts viewers.

In Vice, McKay defends his prowess in explaining a complex issue’s ongoing significance. McKay employs intentionally fast-paced and humorous editing as well as clever metaphorical devices. McKay has honed a particular manner of storytelling which relies on absurdity to make otherwise difficult and boring subjects intelligible and entertaining. In The Big Short for instance, Selena Gomez aids Richard Thaler in explaining collateralized debt obligations with blackjack. In Vice, this satire abounds to a degree which some may find grotesque or trivializing. In one scene, Cheney and other policy-makers of the Bush administration sit down in an opulent restaurant as a waiter lists legally-dubious specials: Employing the concept of the unitary executive, the invasion of Iraq, and bypassing the Geneva Convention. As the men grin, McKay splices in footage of illegal torture and visceral combat in Iraq. This could be read as trivializing, but it highlights how America’s most powerful so flippantly killed more than half a million Iraqis. McKay, who is famous for funny films like Anchorman, uses comedy to expose the stunning stupidity he believes guides global politics.

Bale’s Cheney is a power-obsessed neoconservative determined to cement an American empire and affirm the near-absolutist power of the executive. McKay argues that the decay of government transparency materialized under George W. Bush and was guided by Cheney and his cohorts, including then-counselor and chief-of-staff David Addington. McKay is, perhaps, warning us that the unruly and immoral executive figurehead is less worrying than the invisible actors who work behind him.

McKay caps the film with a simplistic but startling contemporization of Cheney’s rule. He traces the rise of ISIS, the power of conservative television, and even the average American’s confusion about who the enemy is back to Cheney. Vice has stunted pacing and is not quite as fun as The Big Short, which develops likeable though conflicted characters. Still, it is timely and sizzles with the same heat as the current political climate; it is both a history of a pattern and a prophecy of an approaching boiling point.