Every year, Persians meticulously celebrate the exact second that the sun passes the celestial equator, as the spring equinox marks the start of a new year, Nowruz. Nowruz, and most of the traditions that accompany it, have direct roots in Zoroastrianism, one of the oldest religions in the world. Yet, there is one practice with a backstory that remains disputed within the Persian community.

Haji Firuz is a folklore character who heralds the holidays, wearing a red minstrel costume and most notably, a blackened face. Now, ahead of the coming Nowruz and especially in honour of Black History Month, Persians must admit that Haji Firuz is a racist caricature and must finally acknowledge the forgotten history of slavery in Iran.

On the eve of the last Wednesday of the year, Persians celebrate a Zoroastrian practice called Chaharshanbe Suri by jumping over fire to cleanse themselves of sickness and evil. Traditionally, Haji Firuz is believed to have dark skin from the soot of this fire. Yet, this superficial explanation ignores the nuances of his persona that have direct links to slavery.

The man dressed as Haji Firuz carries a tambourine and sings a popular jingle:

“My Master, greetings!

My Master, hold your head up!

My Master, why don’t you laugh?

It’s Nowruz, it’s one day a year!”

Not only does this rhyme reflect his status as an enslaved jester, but Haji Firuz hails from Siah-bazi theatre, which is itself a racist form of entertainment. Siah-bazi, which translates to “playing black,” is no different than the minstrel shows in the United States. Much like how stock characters in those shows mocked enslaved people, characters in Siah-bazi perpetuate a lewd and clownish caricature of Black people.

Those who deny this anti-Blackness continue to excuse Haji Firuz as a centuries old beloved icon who spreads joy during the festivities. Some defenders of Haji Firuz reference misreadings of the famous Persian epic, Shahnameh, as the literary source of the character. Not only do these claims lack factual and historical backing, but they are also tired attempts at erasing Iran’s involvement in slave trade during the Qajar dynasty.

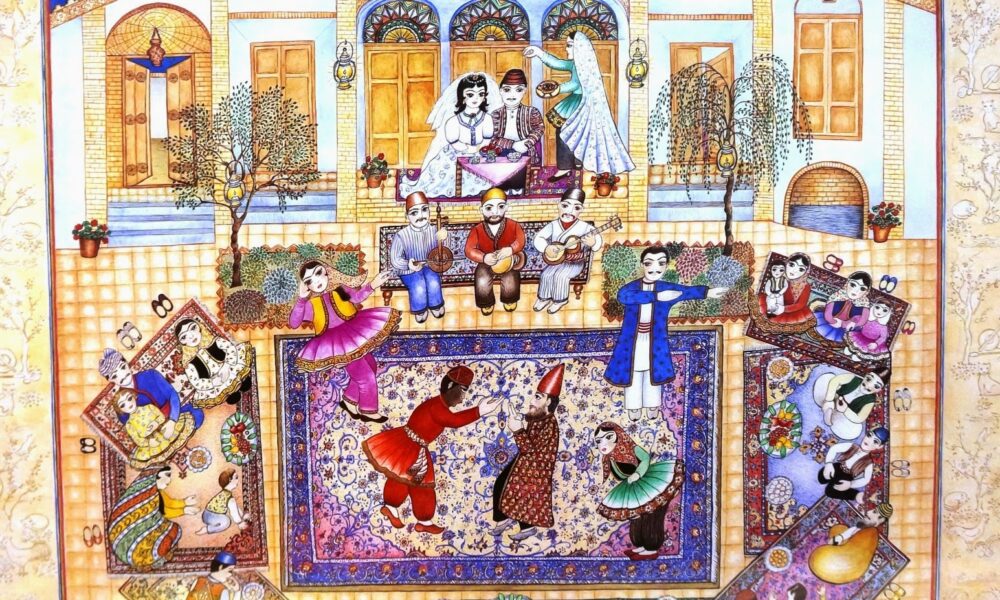

Throughout the late Qajar period, historians estimate that one to two million people from East Africa were enslaved and brought to Iran, where slavery remained legal until Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty finally abolished it in 1929. There exists a temptation to repaint slavery in Iran as a form of mild domestic servitude that was not based on race, especially in comparison to the United States. Yet, even if it may threaten the national pride of some Persians, racialized forced labour existed in Iran in multiple forms, including eunuchism and concubinage. It would be an absurd irony to talk of Iran’s history devoid of any reference to slavery. Haji Firuz is a product of Siah-bazi, which itself is the aftermath to years of racialized slavery. Appreciating Iran’s rich history and criticizing its wrongs are not and should not be mutually exclusive.

Along with the erasure of slavery, the Black Iranian community has often been overlooked. The media’s lack of Afro-Iranian representation has led to an illusion of racial homogeneity in Iran. In 2015, German-Iranian photographer Mahdi Ehsaei created a series featuring photographs of Black Iranians in the Hormozgan province. The name of the collection, Afro-Iran: The Unknown Minority, is enough to demonstrate the neglect experienced by this community. Even so, while the Afro-Iranian community continues to be perceived as less Iranian, their cultural contributions are often viewed as Iranian products. Bandari music and dances, for example, are repeatedly stripped of their Afro-Iranian origins. If Persians enjoy Afro-Iranian art, they must also recognize the presence of Afro-Iranians; they must stand up against anti-Black racism, and they must denounce Haji Firuz and other forms of blackface like Siah-bazi.

So, as you prepare your Haft-Seen arrangements this year, celebrate Chaharshanbe Suri, and play Bandari music during Sizdah-be-dar, remember and remind others that anti-Black racism has no place in our Nowruz festivities or anywhere else in our culture.