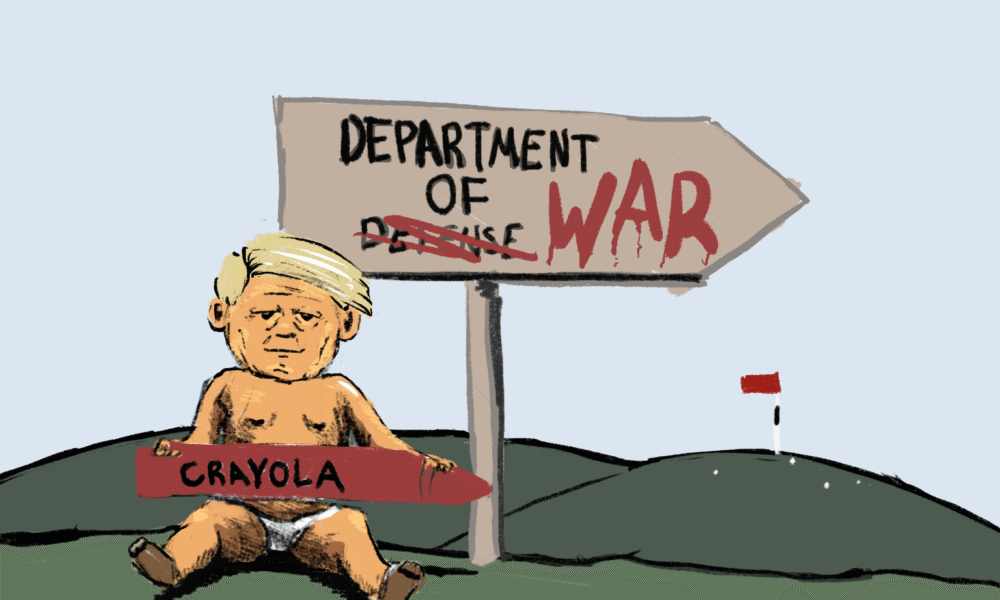

United States President Donald Trump renamed the Department of Defence (DoD) the ‘Department of War’ in an executive order issued on Sept. 5. Subsequently, ‘Secretary of War’ Pete Hegseth stated that the government is “going on offence, not just defence.” The White House’s rebranding of the institution is not a benign change in nomenclature but a symbolic shift to embrace violence in governance. The new department title serves as a prime example of language weaponized to accomplish political goals and influence public perception—a strategy also wielded by educational institutions like McGill.

Trump’s rhetoric surrounding the DoD name change emphasizes victory, strength, and a readiness to engage in warfare to “secure what is ours,” a combative language bordering on imperialistic intent—one that harks back to Trump’s last labelling stunt of renaming the Gulf of Mexico the ‘Gulf of America’ just this January.

The administration’s war on naming speaks more broadly of a will to heroicize America in the eyes of American citizens and the international community. Hegseth glorified violence when he declared that the DoD title change aims to restore “warrior ethos.” Yet, language that celebrates strength and warfare often finds its counterpart in language that disguises domination as diplomacy and violence as peace. Hegseth justified the evolution of the Department of War’s mission by arguing it seeks to bring peace—a comically paradoxical declaration that is a testament to America’s long history of waging devastating wars under the pretense of peace.

The bitter irony of Trump’s ‘peace’ rhetoric is more conspicuous in his 20-point plan announced on Sept. 29, in which he pledged to bring about an ‘everlasting reconciliation’ between Israel and Palestine. The plan aims to establish a transitional government for Gaza, overseen by a ‘Board of Peace’ led by Trump and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

The ‘Board of Peace’ is questionable by definition, given the two key figures appointed as its leaders. First, Blair was responsible for Britain’s decision to back up American troops in the 2003 Iraq war. Second, Trump has displayed nothing short of a flippant attitude towards Israel’s genocide. On Feb. 25, he reposted a concerning AI video imagining the future of Palestine, featuring himself sipping a cocktail by the pool of a luxurious hotel with Israeli leader Benjamin Netanyahu.

Trump leverages the language of war and peace to legitimize and glorify America’s participation in international conflicts—a common rhetorical tactic in high-power politics around the world. Whether it is the Israel Defence Forces title invoking national defence to deny genocidal violence, or Quebec Premier François Legault’s fear-mongering claims of a French Language extinction to rationalize Bill 96, curated rhetoric saturates global politics.

Like politicians, institutional leaders too weaponize rhetoric to shape public perception on political affairs and drown out the objectives and campaigns of social movements. On campus, we have also witnessed firsthand how the ‘peace’ rhetoric often hides a latent and divisive political agenda. At McGill, students and faculty continuously organize against the university’s financial investments in military technology companies tied to the Israeli occupation: This movement has included—but is not limited to—the passing of the Policy Against Genocide in 2023, the McGill Association of University Teachers endorsing an academic and cultural boycott of Israel, the 75-day encampment, and two student strikes for divestment.

However, McGill President and Vice-Chancellor Deep Saini consistently asserts that McGill University must abstain from “commenting or taking a position” when addressing protests. By asserting a supposedly neutral political position, McGill fundamentally sides with the perpetrators of genocide. Abstaining from taking a side in a political conflict is, in effect, siding with the powerful, and is far from an act of peace.

The president of a university is appointed to represent the institution’s interests. President Saini’s condemnation of vandalism advocating for divestment in February is understandable in its aim of protecting McGill property. However, Saini’s systematic refusal to address the motives behind the vandalistic acts dismisses the greater concern of students at hand. By cherry-picking what to comment on and where to claim alleged neutrality, Saini constructs a ‘peace’ rhetoric that maintains the genocidal status quo.

The rhetoric embedded in our political landscapes shapes and distorts depictions of political events. Whether glorifying aggression or masquerading behind the façade of peace, these distortions serve one purpose: To protect power. Students must proceed with caution and consider the intentions and interests underlying seemingly impartial political statements appealing to ‘peace’ or ‘security—especially during times of intense mobilization.