Content warning: This article discusses rape and sexual assault.

How much did you drink? Did you realize you were drunk? Did you take drinks from a stranger at the bar? What were you wearing? Why would you walk home alone? Did you try telling him to stop? These were some of the questions people asked me after I had been raped—including my roommates, the nurse who explained to me what had happened when I woke up, McGill counsellors, and even my mom at one point.

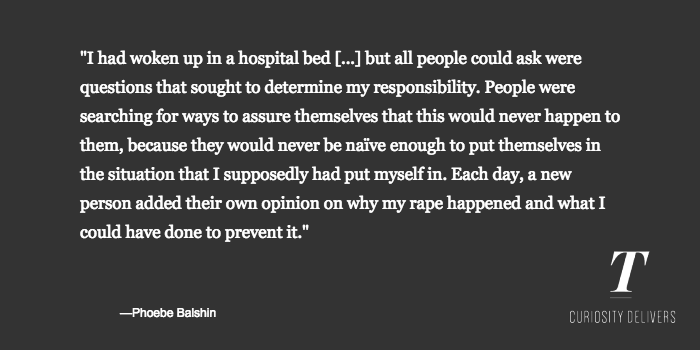

I had woken up in a hospital bed, stripped of my clothes and covered in bruises, but all people could ask were questions that sought to determine my responsibility. People were searching for ways to assure themselves that this would never happen to them, because they would never be naïve enough to put themselves in the situation that I supposedly had put myself in. Each day, a new person added their own opinion on why my rape happened and what I could have done to prevent it. Some days, I didn’t have the energy to talk myself into thinking otherwise, and would succumb to others, truly believing that I was at fault. This is how I came to discover victim blaming.

Victim blaming is when individuals try to justify sexual violence by focusing on the actions of the victim rather than the offender. Victim blaming is a large component of the “rape culture” that pervades university campuses and broader society: Women are predisposed to think they are to blame for their rape even before another person brings it up. From a young age, girls are told over and over again: “Don’t dress provocatively!,” “Don’t walk alone at night,” and “Always keep an eye on your drink.” They are constantly bombarded with techniques to prevent a potential assault. Going to university? Take a self-defence class first. Have class at night? Carry around pepper spray. Taking a cab alone? Stay on the phone with someone. This warped way that society views sexual assault needs to change, as it continuously discourages victims from coming forward and further shames them once they do.

Too often, the media focuses on the culture of binge drinking that correlates with reported assaults, failing to acknowledge the culture of rape that exists on campus. Rape culture describes an environment where rape is not only prevalent—and somewhat ignored—but sexual assault is normalized through the objectification of women’s bodies and misogynistic language. The tendency to focus on the risks of excessive drinking, instead of the root causes of sexual assault on campus, serves as a competing message in the university community. It gives administrators, peers, professors, and parents an immediate factor to blame when someone is sexually assaulted. University students are allowed to drink, and alcohol intake should in no way invalidate the stories of sexual assault survivors. It is crucial that society abandons this behaviour, and shifts its focus to survivor stories and campus reports that reveal the unfortunate existence and prevalence of rape culture.

The tendency to teach women to “be safe” and “smart” perpetuates the false belief that they can prevent rape, and are therefore responsible if it happens to them. Parents in particular can be more mindful, teaching their daughters that it is not their fault, and being cautious in their choice of words when giving women of all ages advice.

Words cannot describe the shame, regret, loneliness, fear, and sadness a person who was raped feels. It is of utmost importance that university communities and society at large do not further contribute to the problem by engaging in questions that offer perpetrators an excuse. Upstream administrators, as well as friends and peers, need to realize how their questions affect victims, and (prepare to) be there for support, rather than interrogation. Instead, ask a victim what you can do to help them. It is difficult to know how to support someone during a traumatic event, but it is essential to think before you ask questions, and realize that certain questions may haunt a victim for years to come.

So, how much did I drink? Four shots and a beer. Did I realize I was drunk? Yes. Did I take drinks from strangers at the bar? No. What was I wearing? A black skirt and a beige tank top. Why did I walk home alone? Because I lived a block away and was tired. Did I tell him to stop? Yes.

Regardless of how much someone has to drink or what they are wearing, a victim of sexual assault is never the one to blame.