One of the major attractions of academia is the ability to make a career out of learning, where one can pursue a life reminiscent of ancient Greek philosophers or Renaissance polymaths. Of course, following one’s research passions depends on funding. Grant applications and email correspondence shape the everyday life of academics, draining time and energy that would be more enjoyably spent pondering lofty ideas.

McGill professors David Ragsdale and Ian Gold took time off from such drudgery on Nov. 19 at the event ‘Synapses and Skepticism’ to discuss their favourite topics at the intersection of neuroscience and philosophy. The two started their academic careers on parallel paths that eventually converged. Ragsdale, a neuroscientist, studied psychology in his undergrad before happening upon the budding field of neuroscience. Today, he contributes to the field through his work on ion channels, proteins that control the movement of electrical signals in the brain. Gold, a philosopher, tackles the puzzle of delusions and the social determinants of psychosis, how human minds make educated guesses about reality, and how these guesses can go awry.

Research on brain function has yielded insight into philosophical questions. Ragsdale cited a famous neuroscience experiment from 1983 that many lauded as definitive evidence that free will does not exist. The researchers measured participants’ brain waves using electrodes on their scalps and asked them to press a button whenever they felt inclined to do so. Using a fast-spinning clock in the participant’s view, they could determine both when the participant felt the conscious intention to press the button, as well as when they actually pressed it.

As expected, the conscious experience of the will to act preceded the act itself. Unexpectedly, though, the brainwave measurements showed a boost in neural activity before the thought arose on a conscious level, indicating that the brain prepared for the action before the participant was even aware of it.

“While the implications of this study are still heavily debated, its results suggest that our feeling of agency in making decisions is an illusion produced by the brain,” Ragsdale said.

Gold’s research on delusions sheds light on another basic philosophical conundrum informed by neuroscience: How to determine what is real and what is not. In response to a student’s question on the relationship between hallucinations and reality, Gold spoke of a now commonly accepted model of the brain’s role linking sensation to conscious perception.

“Rather than simply projecting the raw sensory data coming in, our brains process these inputs and construct an altered picture of the world,” Gold said. “This model suggests that our brains make these educated guesses about incoming sensory information that enable us to act more efficiently.”

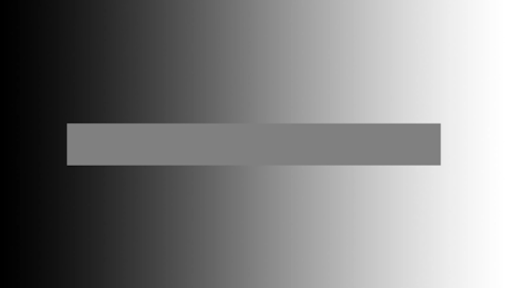

Optical illusions, such as the famous grey bar, are an example of this process. An objective eye seeing the bar will determine that the bar is the same shade throughout its length. But our brains, primed to detect contrast, produce an image that gets darker from left to right. This process stems from evolutionary pressures that have pushed our nervous systems to produce a useful, rather than accurate, perception of the world.

After two hours of discussion, the event concluded with many questions still circling. Left with a hefty dose of head-scratchers, everyone got back on with their lives, neurons firing all cylinders.

Optical illusions such as the famous grey bar illustrate how our brains construct an altered picture of the world.