With the increasing presence of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in everyday life, professors are grappling with the extent to which AI should be allowed in the classroom. Some allow AI as long as usage is disclosed, some strictly prohibit it, and others view it as a tool that encourages students to cheat themselves out of an education. Despite mixed perspectives from its professors, McGill has taken a definitive stance: Integrating AI use into academia.

The university promotes AI usage in its new module on MyCourses titled “Generative AI for Teaching and Learning,” where students and professors alike can explore McGill’s recommended Generative AI (Gen AI) prompts.

The module, designed by Associate Director of Learning Environments for Teaching and Learning Services Adam Finkelstein, offers a variety of services, including prompts to help create semesterly study plans and guides to navigating tricky social situations.

“In 2023 the [Academic Policy Committee’s] Subcommittee on Teaching and Learning (STL) created a working group on AI that drafted recommendations on using Gen AI for teaching and learning at McGill. One of the key recommendations, later received by Senate, was to develop an ongoing university-wide awareness program on using Gen AI in teaching and learning,” Finkelstein wrote to The Tribune.

The module focuses on three key areas: Vitality of using AI ethically and responsibly; Gen AI for teaching support; and Gen AI for student learning support. Finkelstein emphasized the importance of including AI ethics at the beginning of the module, focusing on AI malfunctions like bias and hallucinations, as well as prioritizing safe AI use to protect users’ privacy.

“Part of the rationale for providing examples of how to use Gen AI to support learning is to help close the gap between the students that are already successfully using AI to support their learning and those that have never used it at all,” Finkelstein noted.

Despite controversy among professors and students alike surrounding the extent to which AI should be used in the classroom, Finkelstein maintained that the university must evolve alongside technology.

“AI is here, in almost everything we do, so we need to address it head on and not try to avoid the dialogue on its impact.”

This rhetoric echoes debates that took place following the invention of pocket-sized calculators and their potential use in schools throughout the 1970s. Many worried that calculators would stunt students’ computational abilities and make them overly reliant on machines, preventing them from learning through mistakes. Today, calculators are not only accepted but required for many courses.

However, AI is not the calculator. In fact, calculators are still disallowed in early education to emphasize the importance of young students learning fundamental math skills. The difference with AI is that it has the potential to serve not just as a calculator—an instrument to cut out the middle man of tedious arithmetic—but as a convoluted, robotic writer. While McGill’s Gen AI module encourages the use of AI to cut out the tedium of creating study guides and increasing memory and retention, does it act as a method of damage control, reducing stress and thus reducing cheating? Or does it risk acting as a gateway drug of AI reliance, diminishing students’ necessary exercise of critical thought?

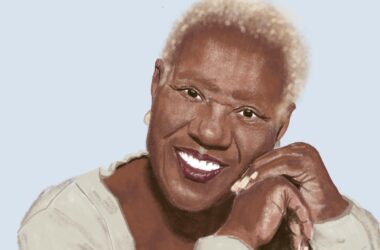

Considering the controversial and highly-debated nature of AI-use in academia, The Tribune sat down with Renee Sieber, associate professor jointly appointed in the School of Environment and the Department of Geography. Named one of the Top 100 Brilliant Women in AI Ethics for 2025, Sieber provided helpful insight into what a future of AI, or a lack of one, could look like.

“Well, first of all, a calculator does not reason,” Sieber told The Tribune concerning the comparison with the calculator. “We tell calculators to do a bunch of steps, but what we’re instead doing is giving the reasoning over to AI, so these are not the same thing.”

Not only is Gen AI incomparable to the calculator, but its side effects are far more detrimental. Sieber emphasized the need to think more critically and ethically about AI use—an aspect she feels is missing in McGill’s Gen AI module.

“There are always problems when one talks about ethics in the classroom, especially in reference to technology, that it is shelved to the last possible moment, compressed into the last week or a single class, instead of being infused, diffused in all aspects of the technology,” Sieber said.

Furthermore, Sieber raised concerns with widespread Gen AI use: On a global scale, AI adoption among larger firms has already been declining since the middle of 2025, as 95 per cent of Gen AI adoptions have found 0 per cent return on investments. Beyond the implications of Gen AI shrinking the entry-level job market, there is a chance that the implementation of Gen AI itself will also soon shrink.

“The venture capitalists that are pumping enormous amounts of money in […] haven’t seen the investment,” Sieber noted. “And when we have this infrastructure, whether it’s a data centre or it’s money—when these run out, what’s going to happen?”

McGill’s Gen AI module encourages AI use among professors—a priority that Sieber worries will result in decreased demand for teaching assistants (TAs). The module for teaching includes sections describing Gen AI use for creating course outlines, developing assessments, and assuring clarity. There are also sections describing how to design AI in or out of a course.

“What makes me very distrustful is that […] the subtext of those modules is you don’t need teaching assistants anymore. You can use the AI to do the work of the teaching assistants or to do your own evaluations.”

She goes on to describe the likely low lifespan of Gen AI, as investment returns are underwhelming and datacentres are running out of internet content to harvest. Her worry is that modules, such as this one, will discourage the hiring of TAs and other teaching support, which will be detrimental in the case that Gen AI dies out sooner than expected.

“It has enormous, incalculable implications for education. So you destroy the infrastructure of education, […] and then we have to regenerate everything. Sometimes you can’t regenerate stuff,” Sieber urged. “You can’t regenerate that stuff after it’s been hollowed out so much.”

Sieber concluded by describing another key aspect she feels the module is missing: How Gen AI can shape how one thinks. Gen AI is often denoted as an objective source, but Sieber argues that this is not completely the case. She references instances where Gen AI has filtered out events of radical activism concerning the protection of the environment, focusing instead on smaller ‘band-aid’ fixes. Though these filters can seem negligible, the wider impact has slow and worrying effects.

“It is changing our brains cognitively and what we think is acceptable in subtle ways,” Sieber described. “You tell the technology something which feeds something back to you, and you get shaped in how you think about the world.”

While Gen AI may seem like a quick and easy solution to hasten the teaching and learning processes, the downsides heavily outweigh its convenience, branching out to many different areas of harm: Accelerating environmental destruction, gutting the infrastructure of institutions beyond repair, and altering the ability to think critically. In a period where Gen AI is pushed as an inevitable technology that must be integrated into our daily lives, it is important to remember the corruption that is entangled within. The tedium of creating a course outline or a study guide is not the enemy, and it surely is worth the protection of our environment, our universities, and our brains.