Ever have friends that didn’t tap their foot, bob their head, or drum their hands to the beat of a good song? Researchers at the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) and the University of Barcelona have discovered that the lack of joy from music can arise biologically, rather than just by choice or taste.

While on sabbatical in Spain, MNI neuroscientist Dr. Robert Zatorre connected with colleagues at the University of Barcelona. Pooling together Zatorre’s knowledge of the brain’s response to pleasure and music and his colleagues’ expertise on anhedonia—the inability to experience pleasure—the team set out to explore the way in which the human brain derives happiness or displeasure from music.

In their resulting study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September 2016, 45 participants filled out a questionnaire regarding the satisfaction they receive from music. The team divided these participants into three categories: Those who “can’t live without music,” those who experience regular joy from music, and those who exhibited no joy from music.

Participants in all three categories listened to music during the scans, voicing whether they liked the music or not. Brain scans using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the subject pool brought an intriguing conclusion to light: The scans projected three different patterns for the three subject pools.

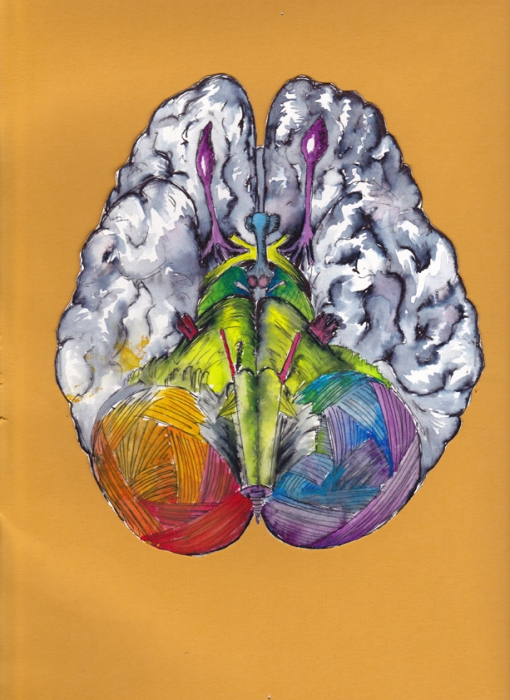

The cortical regions of the brain that control audio processing and the reward system are connected. “Hyper-hedonic” people—those who receive vast amounts of happiness from music—have tightly connected audio and reward systems. On the other hand, individuals who don't experience joy from listening to music have lower connections between these regions than usual. This phenomenon, found in three to five per cent of the population, was dubbed “specific music anhedonia” by the research team.

“There is a whole group of structures called […] the reward circuit,” Zatorre explained. “If there’s activity in that part of the brain, you experience pleasure. If there is no activity in that part of the brain, you experience no pleasure.”

But there are crucial differences between specific music anhedonia and anhedonia in general.

Subjects with specific music anhedonia took a control test. They played an addictive gambling video game so the researchers could focus on their “reward system” response. This test, coupled with verbal questions, revealed normal results—affirming that because the subjects could activate their “reward system” in other ways, the anhedonia they experience must be specific to music.

“[Anhedonia is] a symptom that often occurs in depression and other disorders, like Parkinson’s disease,” Zatorre said. “It refers to the lack of pleasure. The people that we were studying were perfectly fine in terms of their pleasure responses for anything [besides music]. […They] like to be with their friends. They like to be among their families, and have normal, loving relationships like other humans [.…] They like everything, except for music.”

According to Zatorre, subsequent studies seek to explore whether and how these psychiatric conditions may receive more effective treatment—such as a collaborative team at the University of Tel Aviv in Israel, working on the development of a targeted music therapy. Currently, these developments are still experimental.

“The human brain can do a lot of really cool stuff,” Zatorre said.