If art is the exploration of questions, science is the pursuit of answers.

People think, wonder, and imagine. Then they try to hypothesize, conduct, and prove. These processes, however, are difficult without a hefty research grant.

In recent years, funding for research proposals has become more and more competitive, resulting in many of the best proposals being rejected not on merit, but due to a shortage of funding.

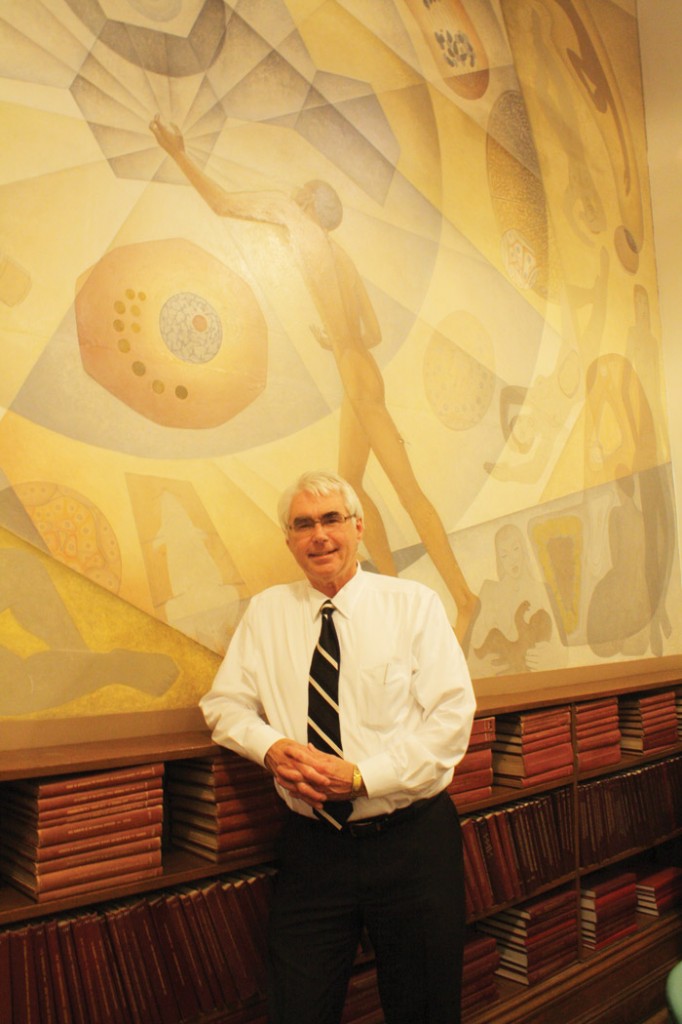

Dr. John Bergeron received his PhD in biochemistry from Oxford University. He has been at McGill since 1974, and was the department chair of Anatomy and Cell Biology from 1996 to 2009. Bergeron, a molecular cell biologist, specializes in organelle proteomics.

According to Bergeron, the key to innovation and discovery lies in the successful education, training, and preparation of young researchers and students.

“Young people make discoveries,” Bergeron said. “They are eager, bold, and are not confined to old ideas.”

Many professors also agreed that the underlying issue for research funding in Canada: Money distribution.

Dr. Monique Zetka, associate professor from the Department of Biology, has been working at McGill University since 2001. Her research is focused on the function and regulation of meiotic chromosome organization, as well as mechanisms of DNA repair.

In describing research grants and money allocated by the medical science industry, Zetka used the term “corporate socialism.” Corporate socialism, known also as corporatism, is defined by Reuters as the organization of a society into groups based on interest, such as scientific affiliation. Essentially, funding is only going to certain groups. For example, funding for ‘discovery research’ and ‘applied research’ can vary.

“Discovery research is the funding for a specific question where it is not apparent what the immediate impact of the discovery would have in the medical industry,” Bergeron said. “Applied research would be investigations carried out in order to find answers with practical commercial applications in mind.” According to Bergeron, applied research is the riskier and less promising of the two.

Dr. Edward Ruthazer, associate professor from the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, has been at McGill since 2005. His research focuses on neural circuits and the connectivity of neurons during biological development.

According to Ruthazer, the decrease in the number of grants allowed is not due to a decrease in funding for research. Rather, the number of labs have gone up while the amount of money for research has stayed the same.

“The top 20 per cent of all grant proposals are virtually indistinguishable in terms of excellence,” Ruthazer said. “However, the reality today is that only about 14 per cent of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant proposals are successful in their applications. Essentially, it becomes a game of chance once a scientist’s grant proposal is in the top 20 per cent because there just isn’t enough money to go around.”

Bergeron highlighted similar statistics.

“The average success rate for a grant proposal in Canada is 15 per cent with an average amount of $120,000 worth of funding,” he said.

Interestingly, methods exist in the U.S. and Europe whereby the most elite researchers, chosen by the EU, are given grants upwards of $1 million a year. Dr. Bergeron says that he would like to see similar grant-awarding mechanisms in Canada.

However, all three researchers stated that there was no issue for them individually with the amount of funding they were receiving.

According to Zetka, a major issue is that too much money is being allocated towards indirect research tied to profit. This is inevitably focused on the medical and life science industry. Profit has a considerable impact in determining how resources are allocated, and Zetka says that industry-tied research is inefficient because the aim is to maximize profit while spreading the risk to taxpayers. Furthermore, in the search for profit, the appeal of pure, unobstructed scientific knowledge often becomes lost.

Unencumbered funding could mean big things for scientists and their research. Given unlimited funding, Ruthazer expressed an interest in unbiased genomic screening in the hopes of discovering new gene targets in neurological diseases. Zetka stated that she would like to study biological mechanisms with respect to time, in the hopes of determining the way proteins are enabled to perform their designated functions.

All three professors emphasized the importance of training for young researchers and students in order to improve opportunities for research grants. Ruthazer referenced the Vanier Doctoral and Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship programs, two initiatives developed by the government of Canada. The programs are prestigious fellowships which come with a very hefty monetary compensation, about twice as much as what a typical researcher at McGill would make.

Ruthazer, while praising the initiative by the government, said that he would like to see the fellowship fund more students, because he believes the key to success lies in the broad support of young researchers.