Money talks. And for the $11 billion Canadian hockey industry, the message is clear: Hockey is more than just a pastime for Canadians. It’s an identity.

The Canadian obsession with hockey, combined with the rise of analytics and sports science, has set the stage for hockey’s own version of the space race. While everyone is looking to discover the next competitive edge, the McGill Ice Hockey Research Group (IHRG) is setting the pace.

“I take an ergonomic analysis approach to the sport,” IHRG Director and Associate Professor of Kinesiology and Physical Education David Pearsall explained. “What tasks […] the athlete does and how does the equipment help them or not help them.”

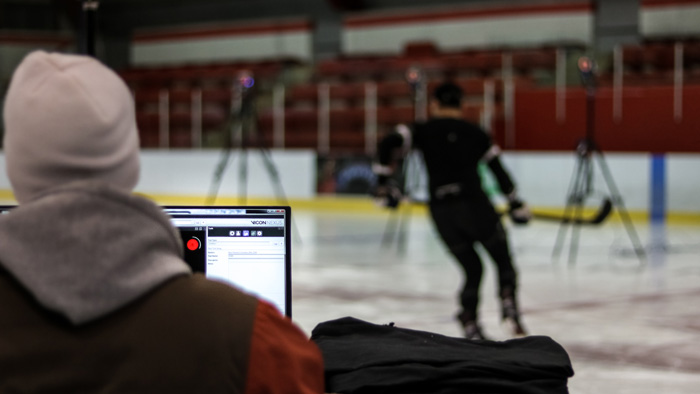

The IHRG aims to innovate hockey equipment to prevent injuries and maximize the efficiency of hockey players’ movements. The IHRG uses 18 3D motion capture cameras to collect information on hockey stick gripping, the accuracy of wrist shots, and more. This process will result in the collection of invaluable and actionable data.

“We want to improve the way [hockey] helmets are made,” IHRG member and PhD candidate Daniel Aponte said. “The [current standardized head-model] was designed in the late 80s and is what’s currently used to make the mold for helmets.”

Studies indicate that many helmet models do little to prevent injury: A recent Virginia Tech team concluded that nine out of thirty-two helmets tested were ‘not recommended’ for reducing the risk of concussion.

“Nobody had really quantified how [the helmets] physically fit yet,” IHRG Master’s student David Greencorn said.

The IHRG’s Helmet Ergonomics and Anthropometry Database (HEAD) study hopes to address this issue. The team aims to design helmets compatible with a variety of head shapes.

“We take a series of pictures of not only people’s head, but also the helmets,” Aponte said. “Then with custom software [we] stitch them together to create a 3D model”.

The IHRG also investigates the biomechanics of player movement and how slight variations in equipment affect performance.

“We have done biomechanics studies that demonstrate how people adapt to different hockey stick stiffness as they shoot,” Pearsall said. “We then use 3D motion and grip force sensor measures to see how people modify their hand grip.”

The IHRG recognizes that many of the findings do not translate smoothly across the sexes and wants to open up the study to include more female athletes.

“Female [players] tend to be more prone to knee injuries, twice the rate they see in males,” Pearsall said. “This suggests different training interventions may be in order.”

Aponte has similar concerns about the potential differences between the sexes found in the HEAD study.

“Female hockey players get the small version of the male stuff, but as head dimensions start to change, it’s not a linear change,” Aponte said. “Just because something is 20 per cent shorter, doesn’t also mean it’s 20 per cent narrower or 20 per cent smaller as a whole.”

As the IHRG continues to strive for the next game-changing competitive edge, the group is also working to translate their findings into usable data for coaches and players. For hockey research, findings are applicable much faster than in most other areas of research. Concussions are common among NHL players and teams must manage injuries in real time.

“We [want to] make what we do more practical, so when [coaches] have those teaching moments [they] can say, ‘Here’s the data’ […],” Pearsall said. “The immediate feedback is what we need to have to help the coaches [….] In hockey, they need the answers now.”